Introduction

Warts or verrucae are a frequently occurring dermatological problem in children (and to a lesser extent, adults). These benign, highly vascular neoplasms affect the plantar surface of the foot as well as other skin surfaces of the feet (also hands and elsewhere). As podiatrists are frequently consulted about these lesions it is important that diagnosis and management be accurate and effective. It is also important that the podiatrist provides good and current information as the ‘plantar wart’ may still conjure potent notions of fear and dread.

Diagnosis

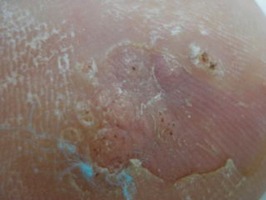

Unlike the raised dome shape of the common wart, plantar warts (by definition located on the sole or plantar surface of the feet) are flattened due to the weight-bearing loads which push them into the skin’s dermis (Fig. 12.1; Bryant et al 2003).

|

| Figure 12.1 |

Plantar warts are often indistinct in initial appearance as there is usually overlying callus. Upon debridement of the overlying callus there are often black spots in the middle of a circumscribed lesion, caused by capillary thrombosis (Gawkrodger 2003). A verruca can grow to half an inch in diameter and may spread into a cluster of small warts, often termed a mosaic wart.

The diagnosis of plantar warts is usually obvious, although they are sometimes confused with corns (heloma dura) or an embedded foreign body. It is very easy to differentiate warts by checking the following clinical signs (Fig. 12.2):

• The ‘squeeze test’: gently squeezing the sides towards the centre of a wart will be painful; not so with a corn; usually not so with a ‘splinter’ (unless already infected).

• Skin line parallels: callus debridement of a wart reveals deviated epidermal ridging (rete ridges) around a wart; the lines remain parallel with a corn or foreign body.

• Location: a wart will not necessarily be adjacent to bone; a typical corn (by definition) will always be adjacent to bone.

If it is not a corn or a splinter, is it definitely a wart?

Usually, but not always, so it is important to include the following differential diagnoses (Gawkrodger 2003, Jennings et al 2006, Young & Cohen 2005):

Key Concepts

• amelanotic melanoma

• fibroma

• molluscum contagiosum (pox virus)

• pyogenic granuloma

• arsenical keratosis

• lichen planus

• squamous cell carcinoma

• basal cell carcinoma

• epidermoid cyst

• xanthoma.

Key Concepts

If the appearance is not typical, definitive diagnosis of questionable lesions should be obtained by skin biopsy (Jennings et al 2006, Levy & Hetherington 1990).

Aetiology

Warts (verrucae) on the feet are caused by the human papilloma virus (HPV) of which there are some 80 different types identified (Gibbs & Harvey 2006). HPV types 1, 2 and 4 are specifically associated, although type 2 is more commonly associated with lesions on the hands rather than the feet (Gawkrodger 2003). HPV incubation time ranges from 4 weeks to 20 months (Jennings et al 2006). HPV is very contagious, but can only be transmitted by direct contact. Infection on the plantar aspect of the foot usually occurs through a small loss of skin integrity as in cuts, fissures and abrasions. HPV thrives in warm, moist environments such as footwear, swimming pools, changing room floors and bathrooms. If an infected bare foot walks across the poolside, there may be a release of virus-infected cells onto the floor. Other people can pick the virus up, especially if small cuts and abrasions are present on their feet which promote the virus’s penetration to become a parasite within the keratinocytes (Levy & Hetherington 1990). Warts tend to be common in children, especially teenagers, where they can seem to reach almost epidemic proportions. However, for unknown reasons, some people seem to be more susceptible to the virus while others are immune (similar to the herpes simplex virus which causes cold sores).

Verrucae usually disappear in time when the host immune system mounts an adequate response, and thus the general policy or clinical wisdom is to only treat warts which are:

• causing pain

• located on the plantar aspect of the feet.

Most verrucae generally resolve spontaneously within 6 months in healthy children, but in adults they can persist for years. It is cited that 50–66% resolve within 2 years (Gibbs et al, 2002 and Gibbs et al, 2006; Kilkenny & Marks 1996; Paller 1996; Young & Cohen 2005).

Prevalence

There have been estimates that some 7–10% of the population may be affected by warts on their feet (Jennings et al 2006). The prevalence has been found to increase with children’s age, with warts (not only plantar) found in 12% of children aged 4–6 years and 24% of 16–18-year-olds (Kilkenny et al 1998).

Typical clinical picture

Classically the child presents with the following story from their parents: their child has been complaining of sore foot and thinks there may be something embedded in it. The site will often determine the level of discomfort, which tends to increase if weight-bearing and as the lesion grows.

When taking the case history of children with verrucae, it is clearly vital that the clinician is familiar with the inclusion/exclusion criteria and appreciative of the concerns raised. Some children and their parents are quite anxious and need to be both informed and reassured. Helpful information may include:

• Positively identifying the lesion – wart vs corn vs splinter vs other.

• Explaining and demonstrating how you have diagnosed a wart (e.g. deviated skin striations, positive ‘squeeze’ test).

• Informing the patient/parent that a wart is a common viral skin infection in children and that on average  resolve within 2 years.

resolve within 2 years.

resolve within 2 years.

resolve within 2 years.• Explaining what a ‘plantar’ wart is and why treatment is often indicated.

• Explaining the best evidence treatment vs many treatment myths.

• Outlining the treatment programme, i.e. frequency of visits, experience of treatment, treatment duration estimate.

• Advising about contagious contact for home care, e.g. shared bathrooms, avoiding bare feet.

Evidence-based management (Table 12.1)

Historically, there has been a veritable plethora of cited ways to treat verrucae. Everything from rubbing the wart with cow dung or an old wash cloth to ‘selling’ the wart and many other options, lotions and potions have been expounded and recommended (Tax 1980, Young & Cohen 2005). The immunological response to the HPV means that warts often resolve spontaneously, yet this can be an event that latently coincides with some form of treatment, rendering the uninitiated patient or clinician confident in the intervention used. Many treatment modes have been employed indicating that none are uniformly effective as most are not directly anti-viral (Parsad et al 1999).

Key Concepts

Key Concepts

Cell mediated immunity (CMI) is generally regarded as the main mechanism for wart regression.

| Salicylic acid preparations have the best evidence for treatment of warts, being supported by a Cochrane Library systematic review. This should be the clinician’s first-line treatment. | ||

| Evidence hierarchy | Interventions | |

|---|---|---|

| ↓ | Systematic review | Salicylic acid |

| Randomized controlled trial | Salicylic acid < div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

| |