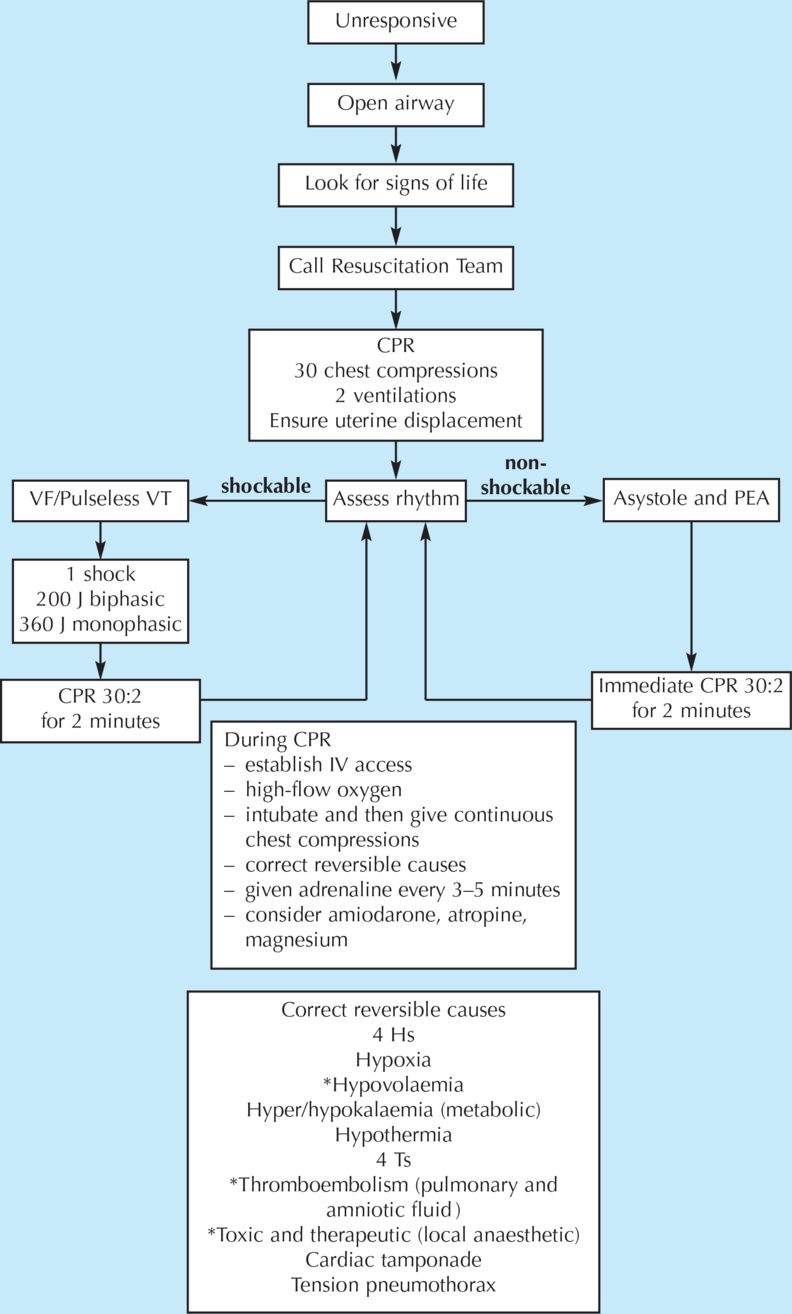

Basic life support: pregnant woman, reproduced with the kind permission of the Resuscitation Council (UK)

Left tilt (or uterine displacement). Empty the uterus if approx. 18–20 weeks onwards. Aim for uterine evacuation within 5 min.

On successfully completing this topic, you will be able to:

understand how to perform basic and advanced life support

understand the importance of early defibrillation where appropriate

understand the adaptations of CPR in the pregnant woman.

Introduction and incidence

Cardiac arrest is estimated to occur in every 30 000 deliveries. Both thromboembolism and amniotic fluid embolism are important causes of maternal death, which may present with sudden collapse. It is important that the healthcare teams know the appropriate actions to take in such an event, to improve outcome for both the mother and the child.

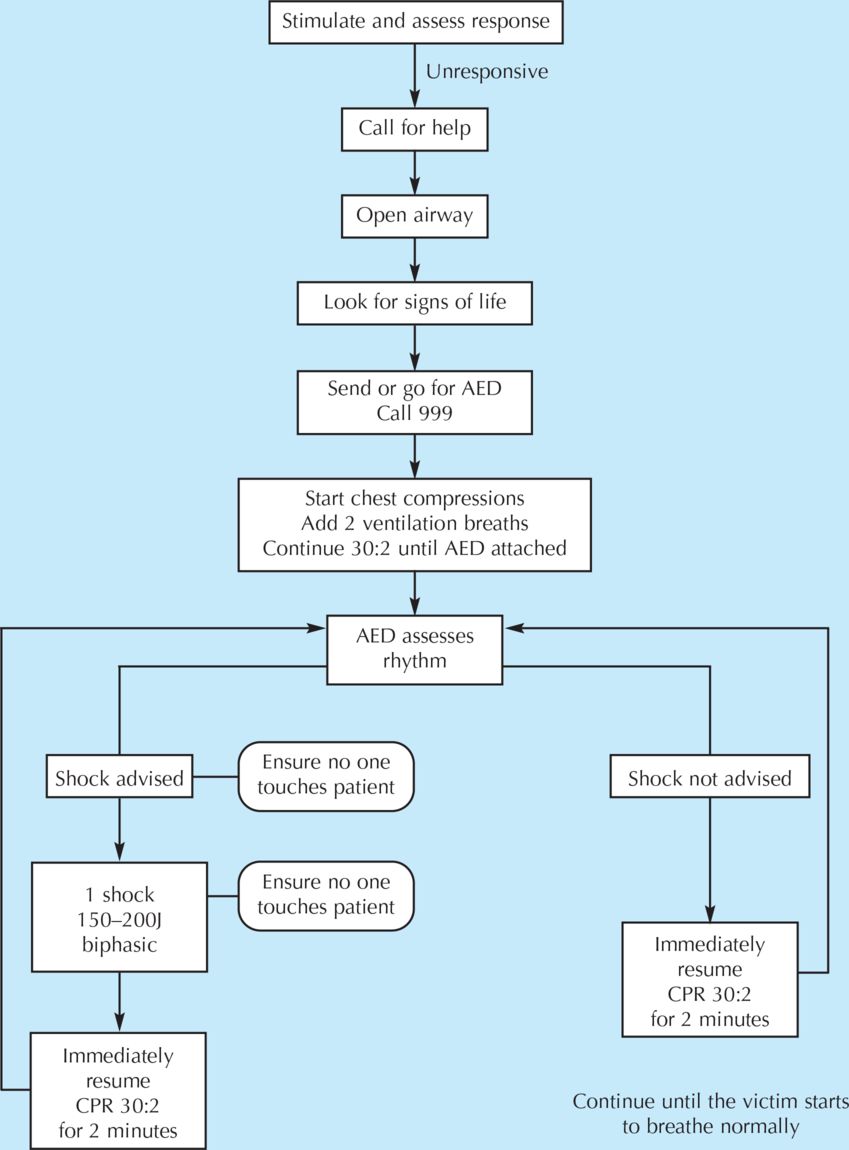

Basic life support

Basic life support describes the procedures that a trained lay person could be expected to provide. These include:

recognising an absence of breathing or other signs of life

knowing to ask for automated external defibrillator (AED) when summoning help

performing chest compressions and mouth to mouth or pocket-mask breathing

(If rescuer not happy to perform mouth to mouth breathing can continue with only chest compressions)

minimising interruptions to chest compression while using AED.

Advanced life support

Advanced life support describes the procedures that a trained healthcare professional could be expected to provide. This includes all of the above, and in addition:

the use of airway adjuncts to provide more effective ventilation

the insertion of intravenous cannulae to give drugs

the use of semi-automated or manual defibrillators.

It should not be necessary to perform mouth to mouth ventilation in a hospital as airway adjuncts should be close to hand.

In a hospital setting, the distinction between basic and advanced life support is arbitrary. The clinical team should be able to provide cardiopulmonary resuscitation, the fundamental components of which are:

rapid recognition of cardiopulmonary collapse

summoning help using a standard procedure/number

starting cardiopulmonary resuscitation using appropriate adjuncts

early defibrillation, when required, if possible within 3 minutes.

Recent guidelines place greater emphasis on high-quality cardiac compressions (‘push hard and fast’) with minimal interruptions.

Management

As shown in Algorithm 9.1, the rescuer must ensure a safe environment. Try to rouse the woman by gently shaking and shouting. If no response, call for help and then return to the woman. If there is no response but there are still ’signs of life‘, then urgent medical attention should be requested and further assessment and appropriate treatment given. Signs of life include:

normal breathing (not agonal gasps)

movement

coughing/gagging.

In the event of little or no signs of life, the following instructions should be carried out, simultaneously if there are multiple helpers, but of necessity are described in an appropriate order for one person.

Turn the woman onto her back with manual uterine displacement (preferable to left tilt)

In a noticeably pregnant woman i.e. one with a significant intra-abdominal mass (by approximately 20 weeks) it is important to minimise aortocaval compression by the uterus (Figure 9.1). This is because aortocaval compression will significantly reduce the output that can be achieved with cardiac compressions.

Open the airway

Open the mouth and briefly check for debris or foreign bodies. Use suction or forceps under direct vision to remove any obstruction, taking care not to cause trauma.

To open the airway, place your hand on the patient’s forehead and gently tilt the head back. At the same time, with your fingertips under the point of the patient’s chin, lift the chin to open the airway. This manoeuvre will straighten the head and neck from a slumped or flexed position, and may slightly extend the head relative to the neck. It allows more space behind the tongue in the posterior pharynx for air movement. In a conscious person, the pharyngeal muscle tone naturally maintains this space for breathing, but will be absent in the unconscious person. An oral airway may be used to provide the same space behind the tongue, with less requirement for vigorous head extension.

A jaw thrust may be required to open the airway. Do this by placing fingers behind both of the angles of the jaw and pushing the jaw anteriorly to displace tongue from the pharynx. If an injury to the neck is suspected, use manual inline stabilisation, avoid head tilt and use jaw thrust to open the airway.

Assess breathing (and signs of life: circulation)

Assess breathing for no more than ten seconds by simultaneously looking for chest movements, listening for breath sounds and feeling for the movement of air. Absence of breathing in the presence of a clear airway is now considered a marker of absence of circulation, along with absence of gagging or movement. Experienced staff may check the carotid pulse for no more than ten seconds at the same time as assessing breathing, but it is important to be aware of how difficult it is for even experienced clinicians to confirm the absence of a pulse and not to waste time before starting chest compressions. ‘Unnecessary’ chest compressions are almost never harmful. Gasping or agonal breathing may occur during cardiac arrest and should not be taken as a sign of life – it is a sign of dying and CPR should commence immediately.

If no circulation (or you are at all unsure) give 30 chest compressions followed by two ventilations

Start CPR

(a) Chest compressions should be applied to the lower half of the sternum. Place the heel of one hand there, with the other hand on top of the first. Interlock the fingers of both hands and lift the fingers to ensure that pressure is not applied over the patient’s ribs. Keep in the midline at all times. Do not apply any pressure over the top of the abdomen or lower tip of the sternum.

(b) Position yourself above the chest and with your arms straight, press down on the sternum to depress 5–6 cm at a rate of 100 to 120 beats/minute in a ratio of 30:2 compressions to ventilations. Change the person doing chest compressions about every 2 minutes to maintain efficiency, but avoid any delays in the changeover.

(c) Ventilation breaths. Keep an open airway and provide ventilation with appropriate adjuncts. This might be a pocket mask, oral airway or self-inflating bag with mask. Oxygen in high flow should be added as soon as possible.

(d) Each breath should last about 1 second and should make the chest rise as if a normal breath. Tracheal intubation should only be undertaken by experienced personnel with minimal interruption to chest compressions. The LMA may be useful as an alternative airway adjunct if intubation cannot be achieved swiftly. Once the woman is intubated, ventilation should continue at a rate of ten breaths per minute, but does not need to be synchronised with chest compressions. These should be continued without interruption.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree