Chapter 40 Vulvar and Vaginal Cancer

Intraepithelial Neoplasia

Intraepithelial Neoplasia

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA IN SITU: VULVAR INTRAEPITHELIAL NEOPLASIA TYPE III

Clinical Features

Itching is the most common symptom, although some patients present with palpable or visible abnormalities of the vulva. About half of patients are asymptomatic. There is no absolutely diagnostic appearance. Most lesions are elevated, but the color may be white, red, pink, gray, or brown (Figure 40-1). About 20% of the lesions have a “warty” appearance, and the lesions are multicentric in about two thirds of cases.

Invasive Vulvar Cancer

Invasive Vulvar Cancer

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for about 90% of vulvar cancers.

Clinical Features

Patients generally present with a vulvar lump, although long-standing pruritus is common. The lesions may be raised, ulcerated, pigmented, or warty in appearance, and definitive diagnosis requires biopsy under local anesthesia. Most lesions occur on the labia majora; the labia minora are the next most common sites. Less commonly, the clitoris or the perineum is involved (Figure 40-2). About 5% of cases are multifocal.

Methods of Spread

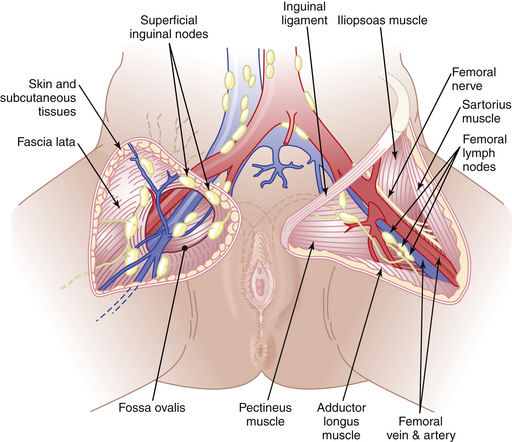

Vulvar cancer spreads by direct extension to adjacent structures, such as the vagina, urethra, and anus; by lymphatic embolization to regional lymph nodes; and by hematogenous spread to distant sites, including the lungs, liver, and bone. In most cases, the initial lymphatic metastases are to the inguinal lymph nodes, located between Camper’s fascia and the fascia lata. From these superficial nodes, spread occurs to the femoral nodes located medial to the femoral vein. Cloquet’s node, which is situated beneath the inguinal ligament, is the most cephalad of the femoral node group. From the inguinofemoral nodes, spread occurs to the pelvic nodes, particularly the external iliac group (Figure 40-3).

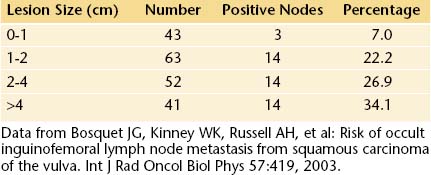

The incidence of lymph node metastases in vulvar cancer is about 30%. It is related to the size of the lesion (Table 40-1). About 5% of patients have metastases to pelvic lymph nodes. Such patients usually have three or more positive unilateral inguinofemoral lymph nodes. Hematogenous spread usually occurs late in the disease and rarely occurs in the absence of lymphatic metastases.

Staging

In 1989, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) Cancer Committee introduced a surgical staging system for vulvar cancer. This system was revised in 1994, and the present FIGO staging system is shown in Table 40-2.

TABLE 40-2 INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF GYNECOLOGY AND OBSTETRICS (FIGO) STAGING OF VULVAR CARCINOMA (1994)

| Stage 0 | Carcinoma in situ, intraepithelial carcinoma |

| Stage I | Tumor confined to the vulva or perineum, or both, and 2 cm or less in greatest dimension; no nodal metastasis |

| Stage Ia | As above with stromal invasion ≤1 mm |

| Stage Ib | As above with stromal invasion >1 mm |

| Stage II | Tumor confined to the vulva or perineum, or both, and more than 2 cm in greatest dimension; no nodal metastasis |

Vulvar Neoplasms

Vulvar Neoplasms