97 Viral Infections

Epstein-Barr Virus

Clinical Presentation

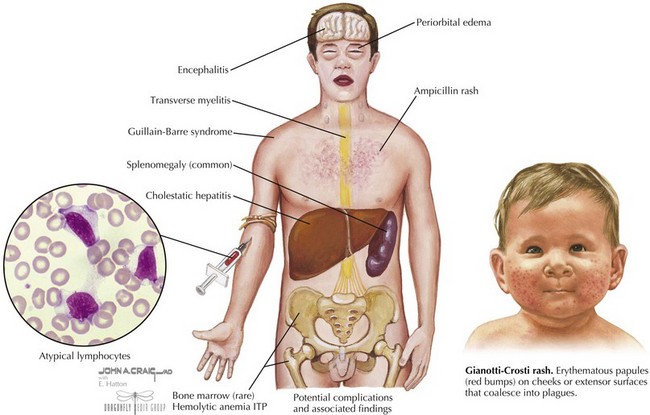

EBV infection causes a wide spectrum of clinical diseases. In many infants and young children, the symptoms are mild or unrecognized. The symptoms of infectious mononucleosis are malaise, fatigue, prolonged fever, sore throat, headache, nausea, and abdominal pain. Patients often have pharyngitis with exudates, lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, or splenomegaly. The incidence of dermatitis may be as high as 15% and is even more pronounced in children who were treated with ampicillin or amoxicillin; it is often called “ampicillin rash” (Figure 97-1). Rare complications of mononucleosis include airway obstruction, central nervous system (CNS) disorders, splenic rupture, thrombocytopenia, and hemolytic anemia.

EBV is also associated with Gianotti-Crosti syndrome in which a symmetric rash is seen on the cheeks, extensor surfaces, or buttocks with multiple erythematous papules, which may coalesce into plaques. This may persist for 15 to 50 days and may sometimes look like atopic dermatitis (see Figure 97-1).

Evaluation and Management

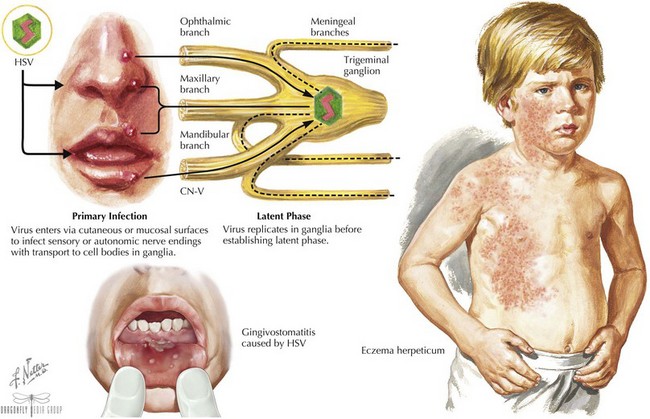

In 90% of cases, there is leukocytosis of 10,000 to 20,000 cells/mm3 with a predominance of lymphocytes with 20% to 40% atypical lymphocytes. There may be a mild thrombocytopenia but usually no purpura, and mild elevations of transaminases can occur. A nonspecific test for heterophile antibodies (also called Monospot) can be done. These are immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies that agglutinate sheep or horse red blood cells (RBCs) and usually appear during the first 2 weeks of illness and gradually disappear over a 6-month period. This test result is often negative in children younger than 4 years old. EBV can also be detected by serologic antibody testing. In the acute phase, there is a rapid immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG response to viral capsid antigen (VCA) and IgG to early antigen(EA). Positive Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen (EBNA) (nuclear antigen) antibody indicates past infection because this is not usually present until several weeks to months after infection (Table 97-1).

Measles

Clinical Presentation

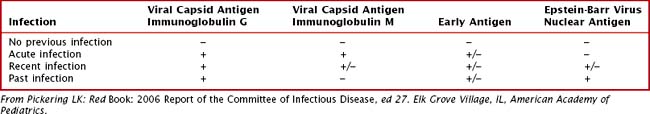

There are four phases to the infection: incubation period, prodrome, exanthem, and recovery. The prodrome period begins with a mild fever that increases to 103° to 105°F, conjunctivitis, coryza, and cough. Koplik spots appear 1 to 4 days before the rash. They appear as red lesions with a bluish white spot in the center and are usually on the inner aspects of the cheek. Rash usually appears after 2 to 4 days and begins on the face as discrete erythematous patches and spreads downward often becoming confluent (Figure 97-2). Lesions are also seen on the palms and soles. Rash fades in about 7 days and may leave desquamation of the skin. Cough can last up to 10 days.

Herpes Simplex Virus

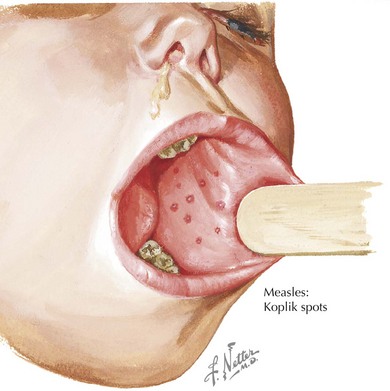

There are 2 types of herpes simplex virus (HSV), type 1 and type 2, that can cause a variety of illnesses depending on the host and the site of infection. A primary herpes infection occurs in those who have never been infected with either HSV-1 or HSV-2. A nonprimary first infection occurs when an individual who was previously infected with one type of HSV then becomes infected with another type. A recurrent infection is a reactivation of the virus from the latent state. HSV can also cause severe neonatal infection (see Chapter 105).

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The virus enters through mucosal surfaces and then spreads via nerve endings to sensory ganglia. Some viruses then establish latency in these sensory neurons (Figure 97-3). The incubation period is usually 2 days to 2 weeks.

Clinical Presentation

The most common clinical manifestation of primary infection in children is gingivostomatitis and is usually caused by HSV-1. It causes sudden onset of pain in the mouth often manifested as refusal to eat, drooling, and high fevers. The gums become very swollen, and vesicles that are usually grouped on an erythematous base are seen throughout the oral cavity, including the gums, lips, tongue, palate, tonsils, and pharynx. The vesicles can progress to ulcers, and lymphadenopathy is often seen (see Figure 97-3). The illness usually resolves in 7 to 14 days.

HSV infections can occur on any skin surface that may have breakdown or trauma. Herpetic whitlow is a term used for HSV infections of the fingers or toes. Lesions and pain usually last for 10 days, and complete recovery usually occurs in 18 to 20 days. Eczema herpeticum is described in patients with a history of eczema who are superinfected with HSV (see Figure 97-3). In addition to severe rash, patients can present with high fevers, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Other areas of the body that may be affected by HSV include the conjunctiva, cornea, and retina as well as the CNS, causing encephalitis and aseptic meningitis. Thus, any vesicles around the eyes should prompt an ophthalmologic examination. HSV has also been implicated in erythema multiforme and Bell’s palsy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree