Chapter 350 Viral Hepatitis

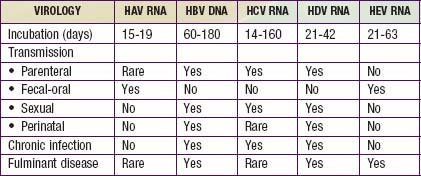

Viral hepatitis continues to be is a major health problem in both developing and developed countries. This disorder is caused by at least 5 pathogenic hepatotropic viruses recognized to date: hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E viruses (Table 350-1). Many other viruses (and diseases) can cause hepatitis, usually as 1 component of a multisystem disease. These include herpes simplex virus (HSV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), varicella-zoster virus, HIV, rubella, adenoviruses, enteroviruses, parvovirus B19, and arboviruses (Table 350-2).

Table 350-2 CAUSES AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF HEPATITIS IN CHILDREN

INFECTIOUS

NON-VIRAL LIVER INFECTIONS

AUTOIMMUNE

METABOLIC

TOXIC

ANATOMIC

HEMODYNAMIC

NON-ALCOHOLIC FATTY LIVER DISEASE

From Wyllie R, Hyams JS, editors: Pediatric gastrointestinal and liver disease, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders.

Issues Common to All Forms of Viral Hepatitis

Common Biochemical Profiles in the Acute Infectious Phase

The most important marker of liver injury is altered synthetic function. Monitoring of synthetic function should be the main focus in clinical follow-up to define the severity of the disease. In the acute phase, the degree of liver synthetic dysfunction guides treatment and helps to establish intervention criteria. Abnormal liver synthetic function is a marker of liver failure and is an indication for prompt referral to a transplant center. Serial assessment is necessary because liver dysfunction does not progress linearly. Synthetic dysfunction is reflected by a combination of abnormal protein synthesis (prolonged prothrombin time, high international normalized ratio [INR], low serum albumin levels), metabolic disturbances (hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis, hyperammonemia), poor clearance of medications dependent on liver function, and altered sensorium with increased deep tendon reflexes (hepatic encephalopathy; Chapter 356).

Hepatitis A

Clinical Manifestations

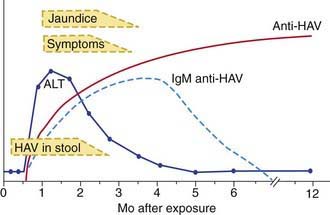

The illness is much more likely to be symptomatic in older adolescents or adults, in patients with underlying liver disorders, and in those who are immunocompromised. It is characteristically an acute febrile illness with an abrupt onset of anorexia, nausea, malaise, vomiting, and jaundice. The typical duration of illness is 7-14 days (Fig. 350-1).

Figure 350-1 The serologic course of acute hepatitis A. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HAV, hepatitis A virus.

(From Goldman L, Ausiello D: Cecil textbook of medicine, ed 22, Philadelphia, 2004, Saunders, p 913.)

Diagnosis

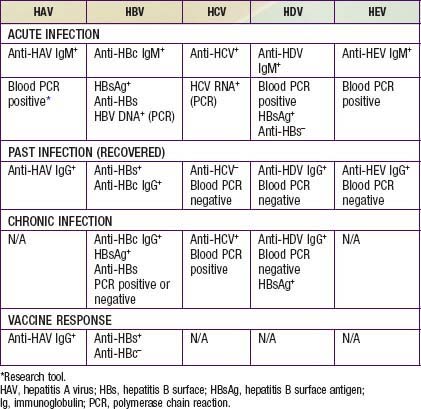

Acute HAV infection is diagnosed by detecting antibodies to HAV, specifically, anti-HAV (IgM) by radioimmunoassay or, rarely, by identifying viral particles in stool. A viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay is available for research use (Table 350-3). Anti-HAV is detectable when the symptoms are clinically apparent, and it remains positive for 4-6 mo after the acute infection. A neutralizing anti-HAV (IgG) is usually detected within 8 wk of symptom onset and is measured as part of a total anti-HAV in the serum. Anti-HAV (IgG) confers long-term protection.

Prevention

Immunoglobulin

Indications for intramuscular administration of immunoglobulin (IG) (0.02 mL/kg) include pre-exposure and postexposure prophylaxis (Table 350-4).

Table 350-4 HEPATITIS A VIRUS PROPHYLAXIS

| PRE-EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS (TRAVELERS TO ENDEMIC REGIONS) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Exposure | Dose |

| <1 yr of age | Expected <3 mo | Ig 0.02 mL/kg |

| Expected 3-5 mo | Ig 0.06 mL/kg | |

| Expected long term | Ig 0.06 mL/kg at departure and every 5 mo thereafter | |

| ≥1 yr of age | Healthy host | HAV vaccine |

| Immunocompromised host, or one with chronic liver disease or chronic health problems | HAV vaccine and Ig 0.02 mL/kg | |

| POSTEXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS* | |

|---|---|

| Exposure | Recommendations |

| ≤2 wk since exposure | < 1 y of age: IG 0.02 mL/kg Immunocompromised host, or host with chronic liver disease or chronic health problems: IG 0.02 mL/kg and HAV vaccine >1 yr and healthy host: HAV vaccine, IG remains optional Sporadic non-household or close contact exposure: prophylaxis not indicated* |

| >2 wk since exposure | None |

Ig, immunoglobulin.

* Decision for prophylaxis in non-household contacts should be tailored to individual exposure and risk.

Vaccine

The availability of two inactivated, highly immunogenic, and safe HAV vaccines has had a major impact on the prevention of HAV infection. Both vaccines are approved for children >1 yr of age. They are administered intramuscularly in a 2-dose schedule, with the 2nd dose given 6-12 mo after the 1st dose. Seroconversion rates in children exceed 90% after an initial dose and approach 100% after the 2nd dose; protective antibody titer persists at least for 10 yr. The immune response in immunocompromised persons, older patients, and those with chronic illnesses may be suboptimal; in those patients, combining the vaccine with IG for pre- and postexposure prophylaxis is indicated. HAV vaccine may be administered simultaneously with other vaccines. A combination HAV and HBV vaccine is currently undergoing trials in adults. For healthy persons >1 yr of age, vaccine is preferable to immunoglobulin for pre-exposure and postexposure prophylaxis (see Table 350-3).