Chapter 646 Vesiculobullous Disorders

Many diseases are characterized by vesiculobullous lesions; they vary considerably in cause, age of onset, and pattern. The morphology of the blister often provides a visual clue to the location of the lesion within the skin. Blisters localized to the epidermal layers are thin-walled, relatively flaccid, and easily ruptured. Subepidermal blisters are tense, thick-walled, and more durable. Biopsies of blisters can be diagnostic because the level of cleavage within the skin and associated findings, such as the nature of the inflammatory infiltrate, are characteristic for a particular disorder. Other diagnostic procedures, such as immunofluorescence and electron microscopy, can often help distinguish vesiculobullous disorders that have nearly identical histopathologic findings (Table 646-1).

Table 646-1 SITES OF BLISTER FORMATION AND DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES FOR THE VESICULOBULLOUS DISORDERS

| DISORDER | BLISTER CLEAVAGE SITE | DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES |

|---|---|---|

| Acrodermatitis enteropathica | IE | Zn level |

| Bullous impetigo | GL | Smear, culture |

| Bullous pemphigoid | SE (junctional) | Direct and indirect immunofluorescence studies |

| Candidosis | SC | KOH preparation, culture |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | SE | Direct immunofluorescence studies |

| Dermatophytosis | IE | KOH preparation, culture |

| Dyshidrotic eczema | IE | Routine histopathology |

| EB—simplex | IE | Electron microscopy; immunofluorescence mapping |

| EB of the hands and feet | IE | Electron microscopy; immunofluorescence mapping |

| Junctional EB (letalis) | SE (junctional) | Electron microscopy; immunofluorescence mapping |

| Recessive dystrophic EB | SE | Electron microscopy; immunofluorescence mapping |

| Dominant dystrophic EB | SE | Electron microscopy; immunofluorescence mapping |

| Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis | IE | Routine histopathology |

| Erythema multiforme | SE | Routine histopathology |

| Erythema toxicum | SC, IE | Smear for eosinophils |

| Incontinentia pigmenti | IE | |

| Insect bites | IE | Routine histopathology |

| Linear IgA dermatosis | SE | Direct immunofluorescence studies |

| Mastocytosis | SE | Routine histopathology |

| Miliaria crystallina | IC | Routine histopathology |

| Neonatal pustular melanosis | SC, IE | Smear for cells |

| Pemphigus foliaceus | GL | Direct and indirect immunofluorescence studies |

| Tzanck smear | ||

| Pemphigus vulgaris | Suprabasal | Direct and indirect immunofluorescence studies |

| Tzanck smear | ||

| Scabies | IE | Scraping |

| Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome | GL | Routine histopathology |

| Toxic epidermal necrolysis | SE | Routine histopathology |

| Viral blisters | IE |

EB, epidermolysis bullosa; GL, granular layer; IC, intracorneal; IE, intraepidermal; KOH, potassium hydroxide; SC, subcorneal; SE, subepidermal.

646.1 Erythema Multiforme

Clinical Manifestations

EM has numerous morphologic manifestations on the skin, varying from erythematous macules, papules, vesicles, bullae, or urticaria-appearing plaques to patches of confluent erythema. The eruption appears most commonly in patients between the ages of 10 and 40 yr and usually is asymptomatic, although a burning sensation or pruritus may be present. The diagnosis of EM is established by finding the classic lesion: doughnut-shaped, target-like (iris or bull’s-eye) papules with an erythematous outer border, an inner pale ring, and a dusky purple to necrotic center (Figs. 646-1 and 646-2).

Gober MD, Laing JM, Burnett JW, et al. The Herpes simplex virus gene Pol expressed in herpes-associated erythema multiforme lesions upregulates/activates SP1 and inflammatory cytokines. Dermatology. 2007;215:97-106.

Lamoreux MR, Sternbach MR, Hsu WT. Erythema multiforme. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1883-1888.

Williams PM, Conklin RJ. Erythema multiforme: a review and contrast from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49:67-76.

646.2 Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

Etiology

Clinical Manifestations

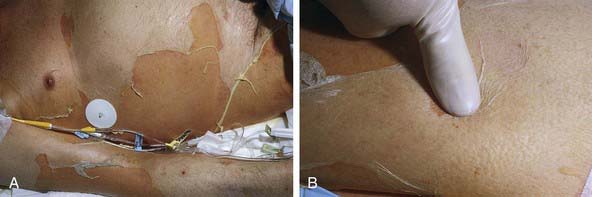

Cutaneous lesions in Stevens-Johnson syndrome generally consist initially of erythematous macules that rapidly and variably develop central necrosis to form vesicles, bullae, and areas of denudation on the face, trunk, and extremities. The skin lesions are typically more widespread than in EM and are accompanied by involvement of two or more mucosal surfaces, namely the eyes, oral cavity, upper airway or esophagus, gastrointestinal tract, or anogenital mucosa (Fig. 646-3). A burning sensation, edema, and erythema of the lips and buccal mucosa are often the presenting signs, followed by development of bullae, ulceration, and hemorrhagic crusting. Lesions may be preceded by a flu-like upper respiratory illness. Pain from mucosal ulceration is often severe, but skin tenderness is minimal to absent in Stevens-Johnson syndrome, in contrast to pain in toxic epidermal necrolysis. Corneal ulceration, anterior uveitis, panophthalmitis, bronchitis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, hepatitis, enterocolitis, polyarthritis, hematuria, and acute tubular necrosis leading to renal failure may occur. Disseminated cutaneous bullae and erosions may result in increased insensible fluid loss and a high risk of bacterial superinfection and sepsis. New lesions occur in crops, and complete healing may take 4-6 wk; ocular scarring, visual impairment, and strictures of the esophagus, bronchi, vagina, urethra, or anus may remain. Nonspecific laboratory abnormalities in Stevens-Johnson syndrome include leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and, occasionally, increased liver transaminase levels and decreased serum albumin values. Toxic epidermal necrolysis is the most severe disorder in the clinical spectrum of the disease, involving considerable constitutional toxicity and extensive necrolysis of the mucous membranes and > 30% of the body surface area (Fig. 646-4).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of Stevens-Johnson syndrome includes toxic epidermal necrolysis, urticaria, DRESS (drug rash [or reaction] with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome (Chapter 637.2) and other drug eruptions and viral exanthems, including Kawasaki disease.