Fig. 45.1

Venous malformation, neck. a Intramuscular VM composed of large, irregular, thin-walled channels. A phlebolith is indicated by arrows. b The channels vary in size and are arranged back to back with scant intervening stroma. c Abnormal venous channels with flat endothelium and thin, variably muscular walls

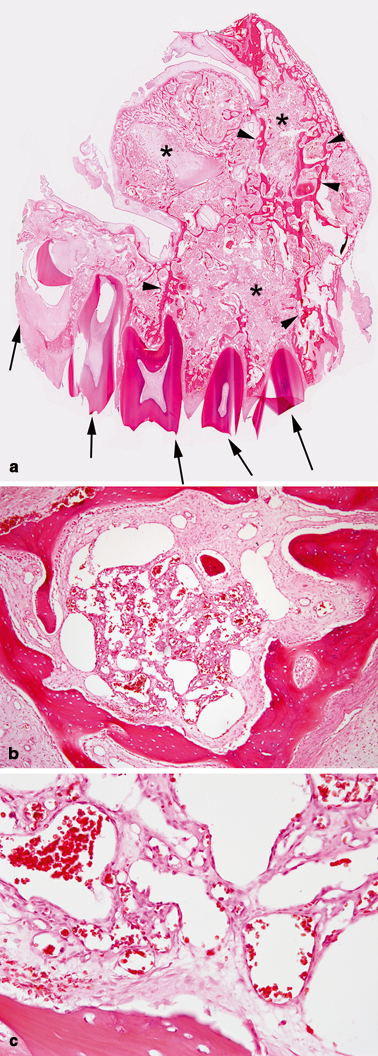

Fig. 45.2

Venous malformation, maxillary bone. a Portion of maxillary bone with intraosseous VM associated with osteolysis (asterisks). Arrows indicate teeth and arrowheads indicate residual trabeculae of bone. b Cluster of intramedullary, thin-walled venous channels of variable size. c Back to back, thin-walled venous channels with flat endothelium and luminal red blood cells

Key Points

VM is particularly problematic because it can expand, especially during adolescence, and often recurs after treatment.

The majority of patients who present with asymptomatic lesions ultimately will require intervention.

VMs should be treated in a vascular anomalies center by a multidisciplinary team.

Biology and Epidemiology

VMs arise from an error in vascular morphogenesis, which results in dilated, thin walled channels of variable size and mural thickness [1]. VM is sporadic and solitary in 90 % of patients; 10 % have multifocal, familial lesions (GVM: 8.0 % or CMVM: 2.0 %) [4, 5].

Pathophysiology

The mechanism for VM enlargement is unknown. Atypical structural characteristics of the vein may predispose the lesion to distention causing stagnation, thrombus, pain, deformation, and/or obstruction [2].

Neovascularization may be involved in VM progression. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and endothelial proliferation are upregulated in cerebral VMs [7–9].

Lesions progress 2.6 times more often in adolescence compared to childhood, indicating that pubertal hormones may be involved in the pathogenesis of VM [2].

Molecular/Genetic Pathology

Sporadic VMs arise from abnormal vasculogenesis; approximately one-half of lesions have a somatic mutation in the endothelial tyrosine kinase receptor TIE2 [4, 5]. Angiopoetins, the ligands for TIE2, are involved with vascular stabilization; the mutation alters endothelial–pericyte contact affecting venous development [5, 10].

GVM is an autosomal dominant condition with abnormal smooth muscle-like glomus cells along the ectatic veins; it is caused by a mutation in the glomulin gene [11, 12].

CMVM is an autosomal dominant disorder produced by a mutation in the TIE2 receptor [10].

Incidence and Prevalence

VMs are the most common vascular malformation treated in a vascular anomalies center, comprising 36.8 % of referrals [16].

Age Distribution

VM is present at birth, but may not become obvious until childhood or adolescence [2].

Sex Predilection

Men and women are affected equally.

Risk Factors

The offspring of patients with GVM, CMVM, or CCM have a 50 % risk of inheriting the condition [11–15].

Progesterone-only oral contraceptives are recommended because estrogen has more potent proangiogenic activity than progesterone [6, 17–20].

Pregnant women do not have an increased risk of VM expansion and thus pregnancy is not contraindicated [2]. Nevertheless, women with significant lesions should be cautioned about possible worsening of symptoms during pregnancy.

Relationships to Other Disease States, Syndromes

Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS) is a rare condition with multiple VMs in the skin, soft tissue, and gastrointestinal tract [21].

Diffuse phlebectasia of Bockenheimer is an extensive extremity VM that affects the skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and bone [22].

Kippel-Trénaunay syndrome (KTS) is an eponym used to describe capillary-lymphatic-venous malformation (CLVM) of an overgrown extremity.

Sinus pericranii is a soft tissue/cutaneous VM of the scalp or face that has a transcranial communication with the dural venous system.

Presentation

Symptoms

Bleeding

Head/neck VM may present with mucosal bleeding.

BRBNS can cause gastrointestinal bleeding and chronic anemia.

Distortion/obstruction of anatomical structures

Head/neck VM may compromise airway or orbital function.

Pain

Caused by thrombosis and phlebolith formation.

VM of muscle may result in fibrosis and contractures.

GVMs are typically more painful than sporadic VM.

Thrombosis

Differential Diagnosis

Arteriovenous malformation (AVM)

Capillary malformation (CM)

Congenital hemangioma (CH)

Infantile hemangioma (IH)

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE)

Lymphatic malformation (LM)

Diagnosis and Evaluation

Physical Examination

Venous Malformation

Approximately 90 % of VMs are diagnosed by history and physical examination [24, 25]. VMs can be small and well localized, or involve multiple tissue planes and important structures. Almost all lesions involve the mucosa, skin, and/or subcutaneous tissue; 50 % also affect deeper structures (e.g., muscle, bone, joints, viscera) [4]. The primary differential diagnosis is LM.

Findings:

VMs are blue, soft, and compressible; dependent positioning may enlarge the lesion.

VMs are usually > 5 cm (56 %) and solitary (99 %), they are located on the extremities (48.3 %), head/neck (30.3 %), trunk (16.6 %), or viscera (4.8 %) [16].

VMs are slow-flow lesions; hand-held Doppler excludes fast-flow vascular anomalies (e.g., AVM, hemangioma) [6].

Glomuvenous Malformation

Patients with a family history of VM should be evaluated for GVM. This condition is autosomal dominant, and individuals are counseled about the risk of transmitting the gene to their offspring [6]. Patients are also predisposed to develop new lesions [4, 12].

Cutaneomucosal-Venous Malformation

Patients with a family history of similar lesions should be examined for CMVM. Individuals are counseled about the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of this condition.

Laboratory Data

Imaging Evaluation

Imaging is usually performed for large or deep VMs. Small, superficial lesions typically do not require radiographical work-up.

Ultrasonography (US)

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Venography

Venography is not required for diagnostic confirmation, but is often performed during sclerotherapy .

Pathology

Histopathological diagnosis of VM is rarely necessary, but may be indicated if imaging is equivocal. Histopathologically, VMs show abnormal, thin-walled venous channels with irregular layers of smooth muscle (see Figs. 45.1 and 45.2) [1]. Vessels frequently have thrombi or phleboliths in their lumens (see Fig. 45.1a) [1]. GVMs are characterized by abnormal venous channels surrounded by characteristic cuboidal myoid “glomus” cells (see Fig. 45.3) [1].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree