123 Vascular Disorders

Vascular lesions of the skin are a common pediatric problem with a wide range of clinical presentations. In 1996, the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies adopted Mulliken and Glowacki’s classification (Table 123-1). There are two categories based on biologic and clinical characteristics: vascular tumors and vascular malformations. Vascular tumors are neoplasms of vascular structures that grow by hyperplasia. Vascular malformations are local anomalies in vascular development that do not demonstrate proliferation.

Table 123-1 International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies Classification of Vascular Anomalies

| Vascular Tumors | Vascular Malformations |

|---|---|

VM, venous malformation.

Adapted from ISSVA classification as reported in Color Atlas of Vascular Tumors & Vascular Malformations.

Vascular Tumors

Infantile Hemangiomas

Clinical Manifestations

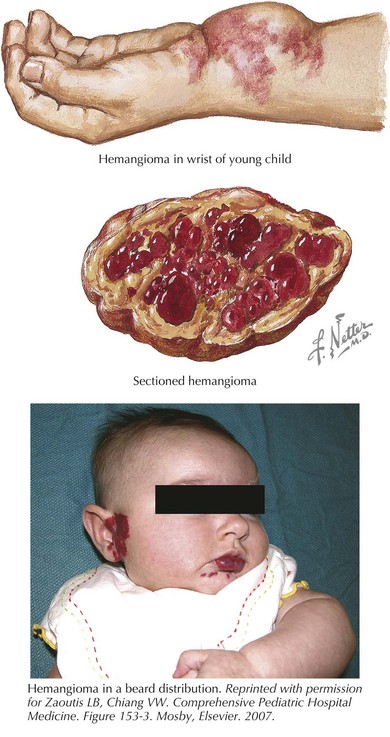

Hemangiomas are classified as superficial, deep, or mixed lesions. Superficial hemangiomas, involving the papillary dermis, are red and protuberant. Superficial hemangiomas have well-defined borders. Deep lesions invade the reticular dermis and superficial fat. They tend to have a blue-purple discoloration with normal skin texture. The margins of deep lesions may be ill defined. Most lesions have both superficial and deep components (Figure 123-1). A mature hemangioma contains characteristics of capillaries, venules, and arterioles.

Management

The most common complication of rapidly proliferating hemangiomas is ulceration. Ulceration is most common in perineal and perioral hemangiomas and can be quite painful. Ulcerated hemangiomas are also at risk for superinfection. Hemangiomas in select locations may have unique complications. Nasal tip hemangiomas cause significant disfigurement. Periocular hemangiomas disrupt visual development, and early referral to an ophthalmologist is prudent. Hemangiomas along the jaw line or neck (beard distribution) of the head and neck (see Figure 123-1) have a high association with airway lesions that may cause life-threatening airway obstruction. Spinal dysraphism is associated with midline lumbosacral lesions, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indicated. Infants with multiple cutaneous hemangiomas warrant evaluation for visceral hemangiomas.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree