HIGINIA R. CÁRDENES  JEANNE M. SCHILDER

JEANNE M. SCHILDER  ROBERT EMERSON

ROBERT EMERSON

ANATOMY

The vagina is a muscular dilatable tubular structure averaging 7.5 cm in length that extends from the cervix to the vulva. It lies dorsal to the base of the bladder and urethra, and ventral to the rectum. The vagina forms from the upward spread of the epithelium from the urogenital sinus. The fused müllerian ducts meet the urogenital sinus at the müllerian tubercle. The hymen marks where the tubercle later opens up to establish the vaginal orifice. The upper portion of the posterior wall is separated from the rectum by a reflection of peritoneum, the pouch of Douglas. At its uppermost extent, the vaginal wall attaches to the uterine cervix at a higher point on the posterior wall than on the anterior wall. During embryonic development, there is no obvious demarcation between the portion of the fused müllerian ducts destined to form the uterus and those destined to form the upper vagina. In the later part of the third month of development, the uterine wall begins to be set off from the upper vagina at the cervical portion. A groove begins to form. This circular groove, formed at the juncture of the vagina and the cervix, is called the fornix.

The vaginal wall is composed of 3 layers: the mucosa, muscularis, and adventitia. The inner mucosal layer is formed by a thick, nonkeratinizing, stratified squamous epithelium overlying a basement membrane containing many papillae. The epithelium normally contains no glands, but is lubricated by mucous secretions originating in the cervix. The epithelium changes little in response to the reproductive cycle. Beneath the mucosa lies a submucosal layer of elastin and a double muscularis layer, highly vascularized with a rich innervation and lymphatic drainage. The muscularis layer is composed of smooth muscle fibers, arranged circularly in the inner portion and longitudinally in the outer portion. A vaginal sphincter is formed by skeletal muscle at the introitus. The adventitia is a thin, outer connective tissue layer that merges with that of adjacent organs.

The proximal vagina is supplied by the vaginal artery branch from the uterine or cervical branch of the uterine artery. It runs along the lateral wall of the vagina and anastomoses with the inferior vesical and middle rectal arteries from the surrounding viscera (1). The accompanying venous plexus, running parallel to the arteries, ultimately drains into the internal iliac vein. The lumbar plexus and pudendal nerve, with branches from the sacral roots 2 to 4, provide innervation to the vaginal vault.

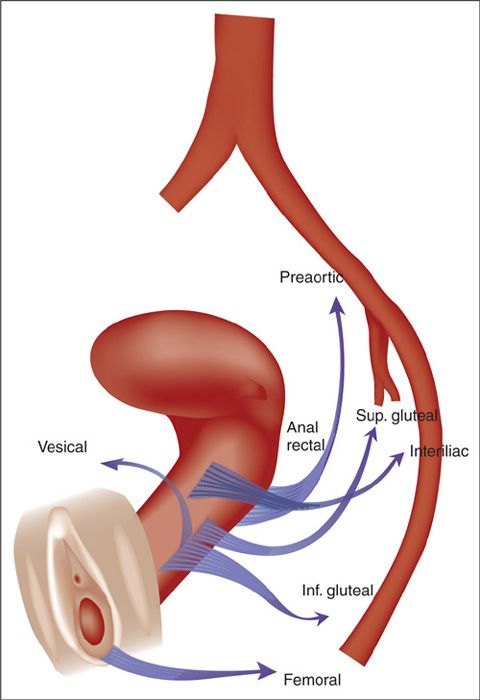

The lymphatic drainage of the vagina is complex, consisting of an extensive intercommunicating network. Fine lymphatic vessels coursing through the submucosa and muscularis coalesce into small trunks running laterally along the walls of the vagina. The lymphatics in the upper portion of the vagina drain primarily via the lymphatics of the cervix; the upper anterior vagina drains along cervical channels to the interiliac and parametrial nodes; the posterior vagina drains into the inferior gluteal, presacral, and anorectal nodes. The distal vagina lymphatics follow drainage patterns of the vulva into the inguinal and femoral nodes and from there to the pelvic nodes. Lymphatic flow from lesions in the mid-vagina may drain either way (Figure 20.1) (2). However, because of the presence of intercommunicating lymphatics along the terminal branches of the vaginal artery and near the vaginal wall, the external iliac nodes are at high risk, even in lesions of the lower third of the vagina.

FIGURE 20.1. Lymphatic drainage of the vagina.

Source: Reprinted from Plentl AA, Friedman EA. Lymphatic system of the female genitalia. In: Plentl AA, Friedman EA, eds. The Morphologic Basis of Oncologic Diagnosis and Therapy. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1971:55, Figure 5-2. Used with permission.

Such a complex lymphatic drainage pattern has significant implications for therapeutic planning. Therefore, bilateral pelvic nodes should be considered at risk in any invasive vaginal carcinoma, and bilateral groin nodes considered at risk in those lesions involving the distal third of the vagina. Although these drainage patterns serve as a general rule, recent data utilizing lymphatic mapping in women with vaginal cancer challenges the established drainage patterns (3). Frumovitz et al. found unexpected lymphatic drainage from primary lesions in the vagina, including 3 of 5 women with lesions located at the introitus that were found to have a sentinel node in the pelvis on pretreatment lymphoscintigraphy, when anatomic site would predict drainage to the inguinal triangle. Conversely, 2 of 4 women who had lesions in the upper third of the vagina were found to have a sentinel node in the inguinofemoral region when anatomic site would predict for involvement of pelvic lymph nodes.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

Primary vaginal cancer is a rare entity, representing only 1% to 2% of all female genital neoplasias. As cervical squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is approximately 50 times more common than vaginal SCC, absence of concurrent cervical SCC or a history of cervical SCC within 5 years is usually considered a requirement for a tumor to be considered a vaginal primary, rather than involvement, or recurrence, of a cervical primary (54,55). Most vaginal neoplasms, 80% to 90%, represent metastasis from other primary gynecologic (cervix or vulva) and nongynecologic sites, involving the vagina by direct extension or lymphatic or hematogenous routes.

Creasman et al. (5) published the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) report in 1998, based on 4,885 patients with primary diagnosis of vaginal cancer registered from 1985 to 1994. Approximately 92% of the patients were diagnosed with in situ or invasive SCC or adenocarcinomas, 4% with melanomas, 3% with sarcomas, and 1% with other or unspecified types of cancer. In the NCDB report, invasive carcinomas accounted for 72% of the carcinoma cases, or 66% of all vaginal cancers. In situ carcinomas accounted for 28% of invasive vaginal carcinomas, SCC represented 79%, and adenocarcinomas represented 14%. Adenocarcinomas represent nearly all the carcinomas in patients younger than 20 years of age and are seen less frequently with advanced age (5). In a more recent Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program (SEER) study by Shah et al. (6), 2,149 women with primary vaginal cancer were diagnosed between 1990 and 2004. Squamous cell histology represented 65% of all cases, followed by adenocarcinomas 14%, melanoma 6%, and the other category representing the remaining 15% (6).

Carcinoma of the vagina is considered to be associated with advanced age, with the peak incidence occurring in the sixth and seventh decades of life. However, vaginal cancer is increasingly being seen in younger women, possibly due to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection or other sexually transmitted diseases. In the NCDB report, only 1% of the carcinoma patients were less than 20 years old at the time of diagnosis, and over 80% of those patients had in situ lesions. As patient age increased, the number of invasive tumors increased, reaching a peak in patients aged 70 to 79 years. The percentage of in situ carcinomas decreased to only 11% in patients over 80 years old (5). A decrease in the incidence of primary vaginal tumors has been noted in recent years, possibly because of early detection with cervical cytology or more rigid diagnostic criteria, which have eliminated from this category primary cancers arising from adjacent organs, such as the cervix, vulva, or endometrium.

Vaginal Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Potential risk factors for SCC include prior history of HPV infection, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), immunosuppression, and possibly previous pelvic irradiation. HPV is the likely etiologic agent of SCC and its precursor lesion, vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN). However, in contrast to cervical SCC, where almost all tumors contain detectable HPV-DNA, many vaginal SCCs are HPV negative. HPV has been detected in about 80% of VAIN lesions and 60% of invasive SCC of the vagina (7). In a case-control study of VAIN and early-stage cancer of the vagina, Brinton et al. (8) reported a 2.9-fold increase in therapy for genital warts and a 3.8-fold increase in prior abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) smears in patients with VAIN compared to controls. The process most commonly occurs in the upper vagina, and it is frequently multifocal. Approximately one-half of the lesions are associated with concomitant CIN or VIN (9).

In studies reporting on groups of women with VAIN and SCC of the vagina, the following risk factors have been identified: 5 or more sexual partners, sexual debut before age 17 years, smoking, low socioeconomic status, a history of genital warts, prior abnormal cytology, and prior hysterectomy (7,8). Weiderpass et al., in a population-based study of 36,856 women, found that alcoholic women had an excess risk for cancer of the vagina, probably related to higher incidence of HPV infection associated with lifestyle factors such as promiscuity, smoking, use of contraceptive hormones, and dietary deficiencies (10). Iversen et al. (11) found no positive correlation between cancer of the penis in husbands and gynecologic cancer in their wives.

Patients with previous cervical carcinoma have a substantial risk of developing vaginal carcinoma, presumably because these sites share exposure and/or susceptibility to endogenous or exogenous carcinogenic stimuli. About 10% to 50% of patients with VAIN–carcinoma in situ (CIS) or invasive carcinoma of the vagina have undergone prior hysterectomy or radiotherapy (RT) for CIS or invasive carcinoma of the cervix (12–23). The interval from therapy for cervical cancer or preinvasive disease to the development of carcinoma of the vagina averages nearly 14 years, but there have been cases with the vaginal primary manifesting 50 years after therapy for cervical cancer (15,24).

It is controversial as to whether or not prior pelvic RT is a risk factor. Boice et al. (126) reported a 14-fold increased risk of cancer of the vagina in previously irradiated women before the age of 45 years, and a dose–response relationship was found to be significant. However, Lee et al. (25), in an analysis of 1,200 patients treated over a 20-year period at Washington University for carcinoma of the cervix, did not find prior RT to be associated with an increase in the incidence of pelvic second neoplasms. It is biologically plausible that there could be an apparent increase in risk given that prior pelvic RT would have likely been given for HPV-associated cervical carcinoma, and the antecedent HPV infection would increase the risk of SCC in the vagina. Such an association has led to the recommendation that patients treated for CIN or carcinoma of the cervix continue to undergo lifelong surveillance with vaginal cytological evaluation even after hysterectomy (26). In addition, Bornstein et al. (27) reported an incidence of CIN and VAIN after in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) twice as high as in unexposed women. The putative mechanism is an enlargement of the transformation zone at risk, which is then at risk for infection with HPV (27).

Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinomas comprise approximately 14% of primary malignancies at this anatomic site (5,52). Primary adenocarcinomas of the vagina may be associated with several presumed precursor lesions including adenosis, endometriosis, and mesonephric rests.

Clear cell adenocarcinoma (CCA) related to in utero DES continues to receive attention as the prototypical example of disease caused by an endocrine-disrupting chemical (61). The incidence of CCA of the vagina and cervix is increased 24-fold in daughters of women who were exposed to DES in utero during the first 16 weeks of pregnancy (28, 62). Specific suggested mechanisms of carcinogenesis focus on the retention of nests of abnormal cells of müllerian duct origin, which, after stimulation by endogenous hormones during puberty, are promoted into adenocarcinomas. The median age at diagnosis in the DES-exposed patients is 19 years (28, 61), whereas prior to this report, most patients with CCA of the vagina were elderly. The incidence of CCA in the exposed female population from birth to 34 years is estimated to be between 0.14 and 1.4 per 1,000. Approximately 90% of the patients had stage I–II disease at diagnosis and most cases involved the anterior upper third of the vaginal wall. Fortunately, the incidence of this tumor has decreased in recent years, and may decrease even more since the practice of prescribing DES during pregnancy has been discontinued. Palmer et al. (30) assessed the influence of postnatal factors on the development of CCA in women exposed to DES in 244 cases compared with 244 age-matched non-DES-exposed women. Neither oral contraceptive use nor pregnancy was associated with risk of CCA (30).

NATURAL HISTORY OF THE DISEASE (PATTERNS OF SPREAD)

The majority (57% to 83%) of vaginal primaries occur in the upper third or at the apex of the vault, most commonly in the posterior wall; the lower third may be involved in as many as 31% of patients (15, 21, 33). Lesions confined to the middle third of the vagina are uncommon. The location of the vaginal carcinoma is an important consideration in planning therapy and determining prognosis. Vaginal tumors may spread along the vaginal walls to involve the cervix or the vulva. However, if biopsies of the cervix or the vulva are positive at the time of initial diagnosis, the tumor cannot be considered a primary vaginal lesion. Because of the absence of anatomic barriers, vaginal tumors readily extend into surrounding tissues, such that a lesion on the anterior wall may infiltrate the vesicovaginal septum and/or the urethra; those on the posterior wall may eventually involve the rectovaginal septum and subsequently infiltrate the rectal mucosa. Lateral extension toward the parametrium and paracolpal tissues is not uncommon in more advanced stages of the disease as well as involvement of the obturator fossa, cardinal ligaments, lateral pelvic walls, and uterosacral ligaments.

The issue of regional nodal metastasis, both the incidence of occult nodal disease and the anatomic pathways of lymphatic spread, is somewhat controversial. The incidence of positive pelvic nodes at diagnosis varies with the stage and location of the primary tumor. Because the lymphatic system of the vagina is so complex, any of the nodal groups may be involved, regardless of the location of the lesion (2). Involvement of inguinal nodes is most common when the lesion is located in the lower third of the vagina. There does seem to be a significant risk of nodal metastasis for patients with disease beyond stage I. Although data on staging lymphadenectomy are sparse, 2 studies reported a significant incidence of nodal disease in early-stage vaginal carcinoma. In Al-Kurdi and Monaghan’s series (34), the incidence of pelvic nodal metastasis was 14% and 32% for stages I and II, respectively, whereas in the Davis et al. series (24), the incidence was 6% and 26% for stages I and II, respectively. The incidence is expected to be higher for stage III, although no substantial data are available. Chyle et al. (14) noted a 10-year actuarial pelvic nodal failure rate of 28% and a 16% inguinal failure rate in patients who had local recurrence, in contrast to 4% and 2%, respectively, in the group without local recurrence (p < 0.001). The incidence of clinically positive inguinal nodes at diagnosis as reported by several authors ranges from 5.3% to 20% (19, 35).

Distant metastasis may occur, primarily in patients with advanced disease at presentation, or those who recurred after primary therapy. In the Perez et al. series (19), the incidence of distant metastasis was 16% in stage I, 31% in stage IIA, 46% in stage IIB, 62% in stage III, and 50% in stage IV. In the largest series reported to date by Hellman et al., distant metastases at diagnosis were rare at 2%, and in 5 of the 7 patients with distant metastases, the tumor involved the entire vagina (36). Robboy et al. reported that metastases to the lungs or supraclavicular lymph nodes represented 35% of recurrences in young women with CCA, a proportion much greater than found with SCC of the cervix or vagina (37).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Vaginal Intraepithelial Neoplasia—Carcinoma In Situ

VAIN most often is asymptomatic (17). In modern practice, VAIN is usually detected by cytological evaluation performed following hysterectomy as part of a surveillance strategy in patients with a history of CIN or invasive cervical carcinoma. In these cases, VAIN has a predilection for involvement of the upper vagina, likely secondary to a “field effect.” A discharge may be present, but is likely secondary to superimposed vaginal infections. It should be noted that evidence-based guidelines do not support routine cytological studies following hysterectomy for noncervical pathology. The American Cancer Society 2012 guidelines indicated that surveillance cytology in such patients is not necessary. Rather, surveillance cytology post hysterectomy should be limited to those patients with a prior history of CIN or invasive cervix cancer (38).

Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma

In patients with invasive disease, irregular vaginal bleeding, often postcoital, is the most common presenting symptom followed by vaginal discharge and dysuria. Pelvic pain is a relatively late symptom generally related to tumor extent beyond the vagina (12). In a series of 84 patients with invasive carcinoma, including 55 with SCC, Tjalma et al. noted that 62% of patients had vaginal discharge, 16% had positive cytology, 13% had a mass, 4% had pain, and 2% had dysuria. Forty-seven percent of the lesions were located on the posterior wall and 24% on the anterior wall; 29% had involvement of both walls (39). In 10% to 20% of the patients, no symptoms were reported, and the diagnosis was made by cytological examination.

Other Histologies

The most common presenting symptom in patients with CCA is vaginal bleeding (50% to 75%) or abnormal discharge. More advanced cases may present with dysuria or pelvic pain (26). Cytology is abnormal in only 33% of cases. Therefore, in addition to 4-quadrant cytology, Hanselaar et al. recommended palpation of the entire vaginal vault to assess for submucosal irregularity (40). The majority of CCA lesions are exophytic, superficially invasive in the upper third of the vault near the cervix.

Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma, the most common malignant vaginal tumor in children, presents as a protruding, edematous grape-like mass. Ninety percent of these sarcomas present before the age of 5 years. The average age at presentation was 23.5 months in the Maurer et al. series (304). In adults, symptoms most commonly noted were pain accompanied by a mass.

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP

In general, in patients with suspected vaginal malignancy, thorough physical examination with detailed speculum inspection, digital palpation, colposcopy and cytological evaluation, and biopsy constitute the most effective procedure for diagnosing primary, metastatic, or recurrent carcinoma of the vagina. In symptomatic patients, biopsy of any abnormal exophytic or endophytic lesion noted at the time of the examination is indicated. Examination under anesthesia is recommended for the thoroughness of evaluation of all of the vaginal walls and local extent of the disease, primarily if the patient is in great discomfort because of advanced disease, in order to obtain a biopsy. Biopsies of the cervix, if present, are recommended to rule out a primary cervical tumor. The speculum must be rotated as it is slowly withdrawn from the vaginal fornix, so that the total vaginal mucosa may be visualized, and, in particular, posterior wall lesions, which occur frequently, are not overlooked.

The patient with a history of preinvasive or invasive carcinoma of the cervix found to have abnormal cytology following prior hysterectomy or RT should be offered vaginoscopy with application of acetic acid to the entire vault, followed by biopsies as indicated by areas of white epithelium, mosaicism, punctation, or atypical vascularity. It can be very helpful for the menopausal patient or the patient previously irradiated to use a short course of topically applied estrogen (Premarin®) into the vaginal vault once or twice a week for 1 month prior to the colposcopy in order to foster epithelial maturation. Another method of identifying the area(s) most in need of biopsy would be, after application of acetic acid, to apply half-strength Schiller’s iodine to determine if the Schiller-positive (nonstaining) areas correspond with the involved areas identified following acetic acid application.

FIGO Staging System for Carcinoma of the Vagina |

Stage | Description |

Stage I | Limited to the vaginal wall |

Stage II | Involvement of the subvaginal tissue but without extension to the pelvic side wall |

Stage III | Extension to the pelvic side wall |

Stage IV | Extension beyond the true pelvis or involvement of the bladder or rectal mucosa. Bullous edema as such does not permit a case to be allotted to Stage IV |

IVA | Spread to adjacent organs and/or direct extension beyond the true pelvis |

IVB | Spread to distant organs |

Source: From FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Current FIGO staging for cancer of the vagina, fallopian tube, ovary, and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;105(1):3–4. Used with permission.

STAGING

The 2 commonly used staging systems for carcinoma of the vagina are the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) (Table 20.1A) (43) and the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) classifications (Table 20.1B) (44). According to FIGO and AJCC guidelines, cases should be classified as vaginal carcinomas only when “the primary site of the growth is in the vagina.” A tumor of the vagina that involves the cervix or vulva should be classified as a primary cervical or vulvar cancer, respectively. It may be difficult or impossible histologically to distinguish a primary vaginal SCC from recurrent cervical or vulvar disease. In this setting, it is unclear whether the vaginal lesion represents a new carcinoma of the vagina, recurrent cervical cancer, or a HPV-related field effect in these patients. Therefore, cervical cytology should be obtained, and directed biopsies if indicated based on abnormal cytology. If a cervical abnormality is visualized or palpated, biopsy is recommended to rule out a primary cervical malignancy. Similarly, the vulva should be carefully inspected, including application of acetic acid, with directed biopsies of abnormally staining epithelium.

American Joint Commission on Cancer Staging of Vaginal Cancer |

Primary Tumor(T)/FIGO |

|

Tx | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

Tis/ | Carcinoma in situ (preinvasive carcinoma) |

T1/I | Tumor confined to the vagina |

T2/II | Tumor invades paravaginal tissues but not to the pelvic wall |

T3/III | Tumor extends to the pelvic wall |

T4/IVA | Tumor invades mucosa of the bladder or rectum and/or extends beyond the pelvis (Bullous edema is not sufficient to classify a tumor as T4) |

Regional Lymph Nodes (N) |

|

Nx | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

N0 | No regional lymph nodes |

N1/III | Pelvic or inguinal lymph node metastasis |

Distant Metastasis (M) |

|

Mx | Distant metastasis cannot be assessed |

M0 | No distant metastasis |

M1/IVB | Distant metastasis |

AJCC Stage Groupings |

|

Stage 0 | Tis N0 M0 |

Stage I | T1 N0 M0 |

Stage II | T2 N0 M0 |

Stage III | T1–3 N1 M0, T3 N0 M0 |

Stage IVA | T4, any N, M0 |

Stage IVB | Any T, any N, M1 |

Source: American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). Vagina. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2010:469–472. Used with permission.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree