CHAPTER 51 Urodynamic investigations

Introduction

Evaluation of lower urinary tract dysfunction

Symptoms of lower urinary tract dysfunction are common amongst women of all ages and are the cause of significant impairment of quality of life (QoL). The Leicestershire Medical Research Council study (Perry et al 2000) estimates that up to 26% of community-dwelling adults have clinically significant symptoms, and up to 2.4% have significant bothersome and socially disabling symptoms, which equates to more than 40 patients per general practitioner in the UK. A thorough assessment of the symptoms, their impact and the cause is key to their successful treatment. The current guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) suggest that the initial assessment must categorize incontinence based on symptoms, and that all patients should be assessed using a 3-day diary along with a urine dipstick (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2006). Initial treatment should be conservative, with urodynamics reserved for refractory or complicated symptoms.

Normal assessment prior to urodynamics includes clinical history in isolation or the additional use of structured questioning or standardized symptom questionnaires. The utility of an accurate history (primarily categorizing incontinence as stress, urge or mixed incontinence) has been confirmed as part of a health technology assessment in the UK (Martin et al 2006), and was subsequently endorsed by NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2006). These guidelines also highlight the role of disease-specific QoL questionnaires which may allow assessment of bothersomeness of symptoms, and these are increasingly used for the assessment of patients with urinary tract dysfunction in both clinical practice and clinical trials. The International Continence Society’s (ICS) standardization document of 2002 also states that subjective, objective and QoL endpoints should be used as three separate measures of outcome (Abrams et al 2002). Ward and Hilton (2008) demonstrated that cure rates varied from 40% to 90% depending on the definition used, highlighting the importance of defining outcome measures accurately.

Urinary symptoms

Urinary symptoms may not consistently reflect the cause of lower urinary tract dysfunction, and hence there is a need for urodynamic investigations (Cundiff et al 1997). Jarvis et al (1980) compared the results of clinical and urodynamic diagnoses for 100 women referred for investigation of lower urinary tract disorders. There was agreement in 68% of cases of urodynamic stress incontinence, but only 51% of cases of overactive bladder. Although nearly all of the women with urodynamic stress incontinence complained of symptoms of stress incontinence, 46% also complained of urgency. Of the women with overactive bladder, 26% also had symptoms of stress incontinence.

Versi et al (1991), using an analysis of symptoms for the prediction of urodynamic stress incontinence in 252 patients, achieved a correct classification of 81% with a false-positive rate of 16%. Lagro-Jansson et al (1991) showed that symptoms of stress incontinence in the absence of symptoms of urge incontinence had a sensitivity of 78%, specificity of 84% and a positive predictive value of 87%. Where stress incontinence is the only symptom reported, urodynamic stress incontinence is likely to be present in over 90% of cases (Farrar et al 1975, Hastie and Moisey 1989). Even when women who only complain of stress incontinence and who have a normal frequency/volume chart are investigated, 65% have urodynamic stress incontinence and 8% have overactive bladder (James et al 1997).

Quality-of-life assessment

Incontinence research requires that morbidity is measured by endpoints that assess different aspects and are not always independent, such as the number of micturitions and volume voided. The relationship of these endpoints to the lives of women is not well understood. For example, do fewer incontinent episodes or reduced volume of an incontinent episode improve QoL? There are probably individual factors involved which are centred around personal psychology, such as measures of hardiness or personal construct (Toozs-Hobson and Loane 2008). QoL measurement makes an attempt to standardize assessment of many aspects of these, including areas such as social, psychological, occupational, domestic, physical and sexual domains.

Wyman et al (1987) used the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire to show that women with overactive bladder experienced greater psychosocial dysfunction as a result of their urinary symptoms than women with urodynamic stress incontinence, although no relationship was found between the questionnaire score and the urinary diary or pad test results. Kobelt et al (1999) showed that the severity of symptoms of incontinence as expressed as frequency of voids and leakage correlates well with the patient’s QoL and health status, as well as the amount that they are willing to pay for a given percentage reduction in their symptoms.

The King’s Health Questionnaire is a good example of a disease-specific QoL questionnaire which incorporates questions about both bothersomeness of symptoms and QoL (Kelleher et al 1997). It was specifically designed for the assessment of women with urinary symptoms, and has been shown to have good sensitivity to clinically relevant improvement in urinary symptoms in clinical practice and clinical trials (Kobelt et al 1999). In one study, the King’s Health Questionnaire was used to assess the outcome of surgery (colposuspension) for the treatment of urodynamic stress incontinence. There was broad general agreement between objective urodynamic changes demonstrating continence as a result of surgery and symptom and QoL score improvements (Bidmead et al 2001). More recently, there have been attempts to integrate and standardize questionnaires with the International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire (http://www.iciq.net/, Avery et al 2004) and the Electronic Personal Assessment Questionnaire (www.epaq-online.co.uk), which have the advantage of being computer based and giving an instant result.

Urodynamic Investigations

Midstream urine specimen

Urodynamic studies are associated with a 1% risk of urinary tract infection (Coptcoat et al 1988), based on the risk of catheterization, so there is no need for women to have routine prophylactic antibiotics. However, women with particular risk factors, such as diabetes, or voiding difficulties should be given prophylactic antibiotics.

Urinary diary

A urinary diary is a simple paper record of when and how much fluid a woman drinks and voids (Figure 51.1). The diary should be completed for a minimum of 3 days (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2006). Leakage episodes are recorded and (ideally) the precipitating event is also noted. The documented record is more accurate than memory alone, having reasonable test–retest reliability, particularly for incontinence episodes (Wyman et al 1991). The functional capacity of the bladder is obtained and polydipsia, as a cause of polyuria, can be excluded. Unfortunately, the diary does not differentiate between the different urodynamic diagnoses (Larsson et al 1991, Larsson and Victor 1992). The urinary diary can also be used as a baseline for monitoring women undergoing bladder retraining. More recently, an electronic version has been launched commercially which ranks bladder capacity as a centile, matched for age and fluid intake (Amundsen et al 2007). This has the added advantage of an inbuilt character-recognition programme to combine the cheap cost of a paper diary with the rapid and accurate data manipulation of a computer system, and makes possible more quantitative clinical measures than are currently feasible.

Pad test

Pad tests differ according to the length of the test and the volume of fluid within the bladder. The ICS has defined a standard 1-h pad test with a 500 ml oral fluid load (Abrams et al 1988). This involves wearing a weighed towel and drinking 500 ml of water 15 min prior to starting the test. The woman performs 30 min of gentle exercise, such as walking and climbing stairs, followed by 15 min of more provocative exercise, including bending, standing and sitting, coughing, hand washing and running, if possible. The towel is then removed and reweighed. An increase in weight of more than 1 g is considered significant. Limitations of the 1-h pad test and an oral fluid load is that it is not reliable unless a fixed bladder volume is used (Lose et al 1988), with other authors suggesting that it has a poor predictive value (Constanti et al 2008) A 24-h pad test correlates well with symptoms of incontinence, has good reproducibility and is positive if the weight gain is over 4 g (Lose et al 1989, Martin et al 2006). The extended pad test is a more lengthy and objective measurement of leakage, and can be used to confirm or refute leakage in those women complaining of stress incontinence which has not been demonstrated on cystometry.

Uroflowmetry

Measurements

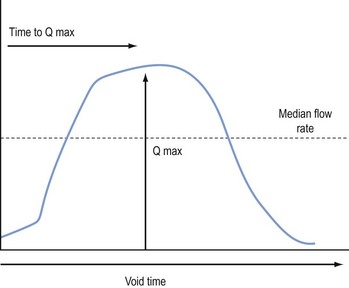

The flow rate is defined as the volume of urine (in ml) expelled from the bladder each second. The flow time is the total duration of the void and includes interruptions in a non-continuous flow. The maximum flow rate is the maximum measured rate of flow, and the average flow is the volume voided divided by the flow time. The total volume voided can be calculated from the area under the flow curve. The two most useful parameters are the maximum flow rate and the voided volume, which should ideally be greater than 150 ml. However, the Liverpool nomograms (Haylen et al 1989) will allow assessment of flow rates at a lower volume. In women with intermittent flow, the same parameters can be used but time intervals between flow episodes must be discounted. Lower volumes at presentation are more likely in the elderly and those of lower parity with a diagnosis of sensory urgency or detrusor overactivity (Haylen et al 2009).

Equipment

There are three main types of flow meter. The gravimetric transducer measures the weight of urine voided over time and this is converted to a flow rate (Figure 51.2). The rotating disc flow meter has a disc spinning at a constant speed. The voided urine slows the rotating disc. The flow rate is calculated from the amount of power needed to maintain the disc spinning at a constant speed. The capacitance flow meter has a metal strip capacitor attached to a plastic dipstick inserted vertically into the jug containing the voided urine. The rate and volume changes are measured by a change in electrical conductance across the capacitor. This is the most expensive type of flow meter, but is robust and very reliable.

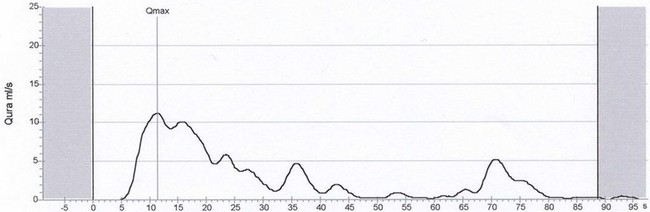

Abnormal flow rates

Nomograms for peak and average urine flow rates in women have been constructed from flow rates of 249 normal women (Haylen et al 1989). These allow comparison of a single value with a standard flow rate. A flow rate below 15 ml/s on more than one occasion is taken as abnormal when the voided volume is above 150 ml as flow rates on smaller volumes are less reliable.

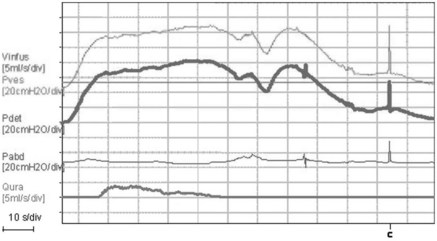

A low peak flow rate and a prolonged voiding time suggest a voiding disorder (Figure 51.3). Straining can give abnormal pressure flow patterns (Figure 51.4) showing a high-pressure, low-flow pattern suggestive of obstruction. The cause of voiding dysfunction may be determined by measuring intravesical pressure simultaneously.

Cystometry

Indications

Cystometry is indicated in patients with symptoms refractory to conservative or simple treatments, or patients with complex symptoms (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2006). However, the validity of the conclusions of NICE have been challenged and management without cystometry may be less accurate (Agur et al 2009).

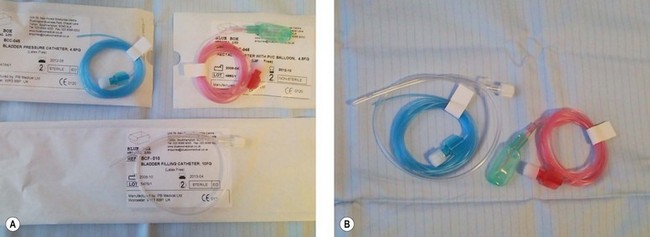

Equipment

Twin-channel cystometry requires two transducers (external or microtip), a recorder and an amplifying unit (Figure 51.5). Bladder pressure is measured using a fluid-filled line attached to an external pressure transducer or a solid-state microtip pressure catheter. A rectal catheter is required to measure abdominal pressure; this is a fluid-filled, 2-mm-diameter catheter covered with a rubber finger cot to prevent blockage with faeces when the catheter is inserted into the rectum (Figure 51.6). The upper edge of the pubic symphysis is the zero reference for all measurements, which are made in centimetres of water (cmH2O). External transducers are cheaper and less fragile, but the microtip transducer does not suffer from movement artefact.

Method

Women attend having completed a bladder diary with a comfortably full bladder. The woman then voids on the flow meter. The woman is then examined and the residual volume is noted on catheterization. During filling, the woman is asked to indicate her first desire to void and the maximal desire to void, and the volumes of these events are noted. There is evidence that women with overactivity may experience different sensations during filling compared with their stress-incontinent comparators (Digesu et al 2009). Systolic detrusor contractions and their association with urgency are noted. Precipitating factors, such as coughing or running water, are also noted. Any symptomatic detrusor pressure rise on standing is again recorded.