- Protein – trace is normal, often due to concentrated urine, but if more than one sample has ≥1+, measure the protein:creatinine ratio. Transient proteinuria may occur with fever or hard exercise. Persistent proteinuria is a feature of nephritis and kidney damage.

- Glucose – either due to a low renal threshold or hyperglycaemia (check blood glucose for diabetes mellitus).

- Haemoglobin – though extremely sensitive, positive reactions are abnormal and usually due to haematuria. Haemoglobinuria and myoglobinuria also produce a positive test, so send for microscopy to identify red cells.

- pH – usually 5 or 6, but is alkaline in infants with pyloric stenosis (see Chapter 21) and sometimes due to urine infection or alkaline medicines.

- Ketones – common with illness, anorexia or vomiting, and in the many school children who have had no breakfast.

- Nitrites and leucocytes – nitrites indicate infection because most urinary pathogens reduce nitrate to nitrite. Excess leucocytes (+ or more) may be the result of any inflammation, including infection. The presence of both leucocytes and nitrites is strongly suggestive of infection, and their absence is reassuring, but a sample should always be sent for microscopy and culture when infection is suspected in a young child.

- Cells – Normal urine should not contain more than 2 red cells × 106/L and 5 (boys) to 50 (girls) white cells × 106/L. The most common causes of haematuria are urinary tract infection and glomerulonephritis.

- Casts are formed in the renal tubules. They may be due to glomerulonephritis when they are made up of red cells (these become granular as cells disintegrate). Hyaline casts devoid of cells are seen in proteinuria.

- Bacteria – Escherichia coli bacteria (the commonest cause of urine infection) appear as gram negative motile rods.

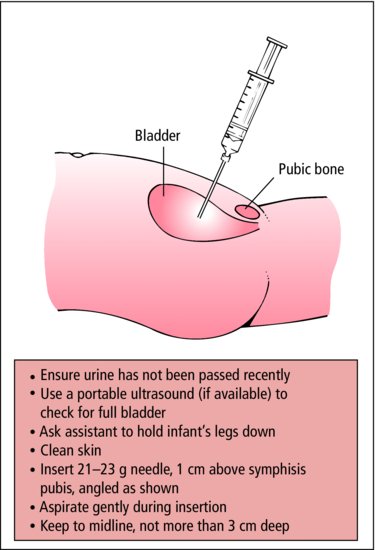

22.2.1.1 Clean catch method

- Have sterile container ready.

- Ensure baby has been fed.

- Wait patiently!

- When baby starts to void, collect into the container.

- Don’t collect until a second or so after voiding has started.

- Try gently tapping the suprapubic region to encourage micturition.

22.2.1.2 Urine-bag method

- Wash genitalia and perineum with water (not antiseptics) and dry.

- Apply bag, ensuring a seal all the way round the genitalia.

- Do not replace a nappy over the bag.

- Remove the bag as soon as the baby has voided.

- Cut a hole in a corner of the bag and allow urine to drain into a sterile container.

PRACTICE POINT Haematuria

PRACTICE POINT Haematuria- Microscopic – detectable only with dipstick and microscopy

- Macroscopic (‘gross’) – visible to the naked eye – urine looks red or smoky brown.

22.3 Congenital anomalies

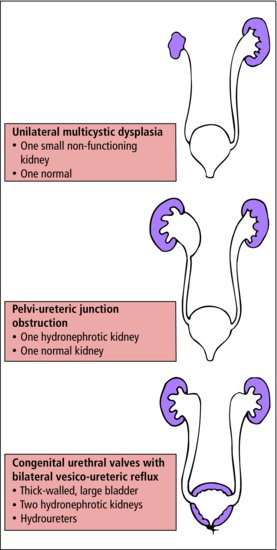

Fetal ultrasound provides warning of many renal abnormalities. Renal agenesis, urethral valves and other obstructive lesions are detected (Figure 22.2).

22.3.1 Renal

22.3.1.1 Agenesis

The ureteric bud fails to develop so that the ureter and kidney are absent. If unilateral, the child may live a healthy life provided the other kidney is normal. Bilateral agenesis is lethal; oligohydramnios is noted during pregnancy, and affected infants have pulmonary hypoplasia and characteristic facial appearance (Potter syndrome).

22.3.1.2 Hypoplastic kidneys

The small kidneys are deficient in renal parenchyma. They are not usually associated with other abnormalities.

22.3.1.3 Dysplastic kidneys

These contain abnormally differentiated parenchyma. They are commonly associated with obstruction and other abnormalities of the urinary tract.

- Massive kidneys

- Renal failure early in life

- Autosomal recessive

- Autosomal dominant

- Kidneys not enlarged, function well during childhood.

22.3.2 Ureteric abnormalities

The most common problem is pelvi-ureteric junction obstruction (PUJO) (Figure 22.2) which may cause hydronephrosis and permanent renal damage. Duplication of the ureter and pelvis may occur on one or both sides. If it only affects the upper half of the ureter, it is not important. If there are two ureters extending down to the bladder with two separate ureteric openings, abnormalities of the lower ureter are common. A ureterocele is a cystic enlargement of the ureter within the bladder which may cause obstruction.

22.3.3 Bladder and urethral abnormalities

22.3.3.1 Posterior urethral valves

These are an important cause of obstruction to urine flow and occur almost exclusively in boys. They are usually detected antenatally, or present in early infancy, as acute obstruction or chronic partial obstruction with dribbling micturition.

Obstruction may cause direct damage by back pressure or predispose to urinary tract infection, which may cause further damage. Most obstructive abnormalities can be corrected by surgery. Obstruction of the lower urinary tract is frequently associated with renal dysplasia.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT22.3.3.2 Hypospadias (Figure 22.3)

The urethral opening is on the ventral surface of the penis. If it is at the junction of the glans and shaft, no treatment is needed, but if it is on the shaft of the penis plastic surgery is required. In all but the mildest cases, there is ventral flexion (chordee) of the penis. There may be associated meatal stenosis.

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINT22.4 Renal disease

22.4.1 Terminology

Note that several different pathologies may be associated with one syndrome, and vice versa. For instance, proliferative glomerulonephritis may be found in several different clinical syndromes. One syndrome may be associated with several different morphological pictures, and have several different aetiologies.

- SYNDROMES: collection of symptoms and signs, e.g. acute nephritic syndrome, nephrotic syndrome

- PATHOLOGY: results of biopsy, e.g. proliferative glomerulonephritis, minimal changes

- AETIOLOGY: e.g. diabetic, poststreptococcal.

The most important syndromes of renal disease in childhood are:

- Acute nephritic syndrome

- Recurrent haematuria

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Symptomless proteinuria

- Renal calculi

- Renal insufficiency.

- Symptomless proteinuria

22.4.2 Acute nephritic syndrome

Renal inflammation provoked by deposition of immune complexes causing:

Renal inflammation provoked by deposition of immune complexes causing:- Haematuria

- Oliguria

- Hypertension

- Raised serum creatinine.

22.4.2.1 Aetiology

The best-known form is poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, which usually occurs 2–3 weeks after a β-haemolytic streptococcal throat infection. Immune complexes composed of streptococci, antibody and complement are deposited in the glomeruli. This provokes proliferation of the endothelial cells (proliferative glomerulonephritis). Although now rare in developed countries, it is common worldwide.

An acute nephritic syndrome may also occur at the time of pneumococcal pneumonia, septicaemia, glandular fever and other viral infections. It is sometimes seen in Henoch–Schönlein syndrome (Section 23.3.5) and the collagen diseases.

22.4.2.2 Features

- Age 3+ (peak 7 years)

- Sudden onset of illness 2–3 weeks after pharyngitis

- Coca-cola coloured urine

- Facial oedema (especially eyelids)

- Abdominal or loin pain

- ↑ blood pressure.

22.4.2.3 Investigations

A small volume of blood-stained urine is passed. In addition to copious red blood cells there is an excess of white cells and proteinuria. Red cell and granular casts are present. The serum creatinine is raised in two-thirds of children. If the cause is streptococcal, ASO titre is raised and serum complement is reduced. Blood pressure is raised.

22.4.2.4 Course and treatment

Oliguria lasts for only a few days. Diuresis usually occurs within a week and is accompanied by return of serum creatinine and blood pressure to normal. The haematuria and proteinuria gradually subside over the next year. During the oliguric phase, fluid and protein are restricted, but it is rarely necessary to start a strict renal failure regime. Other treatment is symptomatic. Over 80% make a full recovery, but a few develop progressive renal disease.

22.4.3 Recurrent haematuria syndrome

KEY POINTS

KEY POINTS- Episodes of haematuria

- Association with exercise, or systemic infection

- Red cell and granular casts in the urine.

The bouts of haematuria usually occur at the time of a systemic infection or exertion. The haematuria results from nephritis of unknown cause. The child may feel unwell but more often has no symptoms. The urine contains red cell and granular casts.

Between attacks the urine is normal or shows microscopic haematuria. Proteinuria is less common and may indicate more serious renal disease. Investigations are done to exclude other causes of haematuria: urine culture, ultrasound scan and intravenous pyelogram for a tumour or stone, and screening tests for bleeding disorders.

- Renal – brown colour, glomerular casts, features of nephritis

- Lower tract – red, may vary with phase of micturition (e.g. terminal haematuria)

- Urine infection (UTI symptoms? – positive microscopy and culture)

- Glomerulonephritis (check BP, do U&Es, ASOT, complement)

- Recurrent haematuria syndrome

- Tumour (abdominal mass? – renal USS)

- Bleeding diathesis (other bleeding or easy bruising? – clotting screen)

- Trauma

- Urinary stones and hypercalcuria (family history?)

- Drugs.

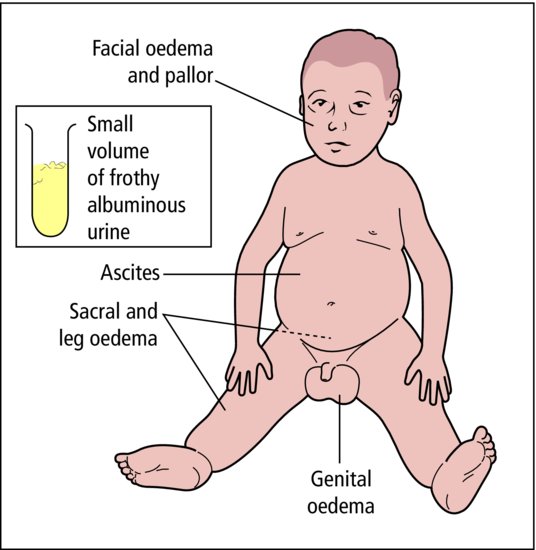

22.4.3.1 Nephrotic syndrome

Glomeruli become leaky to protein (cause unknown) resulting in:

Glomeruli become leaky to protein (cause unknown) resulting in:- Heavy proteinuria

- Hypo-albuminaemia

- Oedema.

22.4.3.2 Features

Peak onset is between the ages of 2 and 5 years. Apart from the gradual onset of generalized oedema, the child may be only mildly off colour. Other symptoms are directly related to oedema, for instance discomfort from ascites or breathlessness from pleural effusion (Figure 22.4).

22.4.3.3 Aetiology

Over 90% of childhood nephrotic syndrome is the result of primary renal disease of unknown cause. Nephrotic syndrome secondary to systemic illness is less common than in adults, the least rare cause being Henoch–Schönlein syndrome (Section 23.3.5). In Africa, malaria is an important cause.

22.4.3.4 Pathology

Up to the age of 5 years, over 80% of affected children show no significant abnormality on renal biopsy, hence the term ‘minimal change disease’, which has a good prognosis. After the age of 10, more serious pathology becomes likely.

22.4.3.5 Investigations

The urine is frothy and there is heavy albuminuria. Highly selective proteinuria, i.e. urine containing a high proportion of small molecular weight proteins, is a good prognostic feature suggesting minimal change histology. Hyaline casts are abundant. Serum albumin is below 25 g/L and the serum cholesterol is usually raised. Serum creatinine is usually normal (Table 22.2).

Table 22.2 Acute nephritic and nephrotic syndromes

| Acute nephritic | Nephrotic | |

| syndrome | syndrome | |

| Child | ||

| Oedema | Mild facial | Gross |

| Blood pressure | Raised | Normal |

| Urine | ||

| Albumin | + + | + + + + |

| RBC | + + + + | 0 or + |

| WBC | + + | 0 |

| Casts | Cellular/granular | Hyaline |

| Bacteria | 0 | 0 |

| Serum | ||

| Albumin | Normal | Low |

22.4.3.6 Treatment and prognosis

Corticosteroids are given in large doses for 4 weeks. While there is oedema, fluid and salt are restricted: diuretics may be needed if the oedema is causing symptoms. Most children go into remission within 2 weeks of starting steroids. Diuresis occurs and the oedema and albuminuria disappear rapidly. A large proportion relapse within the next year. They can be given further courses of steroids, but if the relapses are frequent, cyclophosphamide will usually produce a longer remission.

The long-term prognosis is good. Although frequent relapses can be most troublesome during childhood, with increasing age they become less frequent and most children grow out of the condition by the time they are adults and thereafter have normal renal function and good health. A few (mainly those initially unresponsive to steroids) develop renal insufficiency.

22.4.4 Symptomless proteinuria

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree