CHAPTER 9 Urinary Complaints

URINARY TRACT INFECTION

Urinary tract infection (UTI) refers to the presence of microbes anywhere in the urinary tract, ranging from the distal urethra to the kidney. UTI in the kidney is called pyelonephritis; in the bladder, cystitis; and in the urethra, urethritis. Infection is usually caused by bacteria, particularly E. coli, which accounts for 85% to 90% of all UTIs, but also may be caused by other bacteria, viral, and fungal infection. Klebsiella, Proteus, and Pseudomonas are commonly associated with UTI, particularly in recurrent cases. Urine itself is normally sterile, but the moist environment of the periurethral area, the proximity of the urethral orifice to the rectum, and the short length of the urethra provide a conducive environment for the growth and ascension of potential uropathogenic microorganisms into the urinary system. The presence of bacteria in the urine is called bacteriuria. In nonpregnant women bacteriuria in the absence of symptoms is not considered an indication for treatment; however, during pregnancy, bacteriuria is associated with increased risk of pyelonephritis as well as prematurity and possibly other complications; therefore, UTI in pregnancy requires special consideration. 1 2 3

UTI INCIDENCE AND ETIOLOGY

It is estimated that several hundred million women suffer from UTI annually, with costs to health care providers amounting to over $6 billion annually worldwide, a figure that may even be an underestimate.4 Additional costs to society of UTI are tremendous in terms of the personal suffering of millions of women annually, lost work days, and childcare costs. Over 56% of women will experience a UTI in their lifetimes, and among those experiencing uncomplicated acute UTI, as many as 20% will have a recurrence within 6 months. Overall UTI recurrence rate is between 27% and 48%.4 Even with treatment, symptoms typically last for an average of 6 days, with nearly 2.5 days of limited activity. The rates of UTI are slightly higher in young, sexually active women because of mechanical factors affecting the urethra and the presence of uropathogenic organisms. UTI rates increase during pregnancy and with age, the former because of mechanical pressure of the growing uterus on the ureters and bladder preventing complete voiding, and the latter because of declining estrogen levels, declining mucin (a surface coating of the bladder epithelium that prevents bacterial adhesion), inability to void completely, incontinence, inadequate nutrition, and the occurrence of other disease and excessive catheter use as a result of medical procedures.

RISK FACTORS FOR URINARY TRACT INFECTION

A number of common factors appear to increase the risk of developing a UTI. As mentioned, sexual activity is associated with a higher incidence of symptomatic UTI; however, risk only seems to be increased in the presence of uropathogenic microorganisms, either from a woman’s own reservoir of bowel microbes, or passed from a sexual partner. Urinating after sexual activity decreases the rates of infection. Evidence suggests that host genetic factors influence susceptibility to UTI. A maternal history of UTI is more often found among women who have experienced recurrent UTIs than among controls. Susceptible patients may have a genetically increased number of receptors on uroepithelial cells to which bacteria may adhere. Additionally, nonsecretors of specific blood group antigens, which are glycoproteins, are at increased risk of recurrent UTI. Mutations in host genes integral to the immune response (interferon receptors and others) also may affect susceptibility to UTI.3 The use of oral contraceptives doubles the risk of UTI compared with no birth control, and the use of diaphragms and spermicides doubles the rate of UTI compared with OCs. Sexually transmitted infections and vaginitis can cause urethritis. Dehydration can increase bacterial growth leading to UTI. A history of antibiotic use is common in women with a UTI; a possible mechanism that has been suggested is disruption of the vaginal flora and consequently overgrowth of pathogenic organisms. An interesting correlation exists between recurrent UTI and exposure to cold. A case-controlled study demonstrated a higher rate of UTI in women who reported cold hands, feet, or buttocks in women with UTI than controls. In a nonrandomized crossover study, cooling the feet of 29 healthy women with a history of recurrent UTI led to the development of UTI in five participants, compared with no UTI development in the control group.1

SYMPTOMS

Pyelonephritis commonly has a gradual onset, although it can seem sudden if preceded by lower UTI, and is associated with not only urinary symptoms, but generalized symptoms such as fever, chills, nausea, malaise, and mild to extremely severe lower to middle back discomfort. Patients with pyelonephritis may appear quite ill. It is critical to differentiate between the symptoms of cystitis and pyelonephritis, as the latter requires more aggressive treatment and carries greater risks, particularly during pregnancy (Box 9-1). Cystitis may resolve spontaneously; however, effective treatment lessens the duration of symptoms and reduces the incidence of progression to upper UTI. Pyelonephritis is associated with substantial morbidity. Complications include acute papillary necrosis with possible development of urethral obstruction, septic shock, and perinephric abscess. Chronic pyelonephritis may lead to scarring with diminished renal function.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Primary differential diagnoses include urethritis, cystitis, and pyelonephritis.2 In women with recurring infection, it is important to differentiate between relapse and reinfection. Additional considerations for acute or chronic UTI include:5

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT APPROACHES

Oral antibiotics effective against gram-negative aerobic coliform bacteria, particularly E. coli, is the principal treatment in patients with UTI. A 3-day course is typical in patients with an uncomplicated lower UTI or simple cystitis with symptoms for less than 48 hours. A bladder analgesic may be given if the patient has intense dysuria. Increased fluid intake is often recommended to promote dilute urine flow. Pregnant, otherwise healthy women with no evidence of an upper UTI may be treated with a 7- to 10-day course of a cephalosporin, such as cephalexin, even in the absence of upper urinary tract signs. Pregnant women are typically treated for all episodes of bacteriuria, even in the absence of symptoms. Upper UTI requires antibiotic treatment and may require IV therapy and hospitalization. In most cases, pyelonephritis responds to antibiotic treatment in 48 to 72 hours.5 Therapeutic approaches to treatment and prevention of urogenital infections have remained essentially unchanged for many years. Antibiotics and antifungals remain the mainstay of therapy. Several antibiotic therapies have become less effective because of antibiotic resistance, and the use of antibiotics in pregnancy often leads to vaginal yeast infection requiring treatment.6

Lifestyle changes may be recommended, such as teaching the client to void at the first urge to urinate, void after intercourse, drink adequate fluids, and avoid contraceptives associated with high UTI risk. Estrogen cream may be recommended for older women.1,2 Other risk factors may include use of menstrual pads (i.e., rather than tampons), wiping the anogenital region from back to front after a bowel movement (front to back is the proper motion), wearing nonabsorbent underpants or pantyhose, and bubble baths with irritating soaps; however, none of these factors have been found to be significant in clinical trials.1 Increasingly, conventional practitioners are recommending the use of cranberry juice and vitamin C for UTI treatment. These are discussed under Botanical Protocol.

THE BOTANICAL PRACTITIONER’S PERSPECTIVE

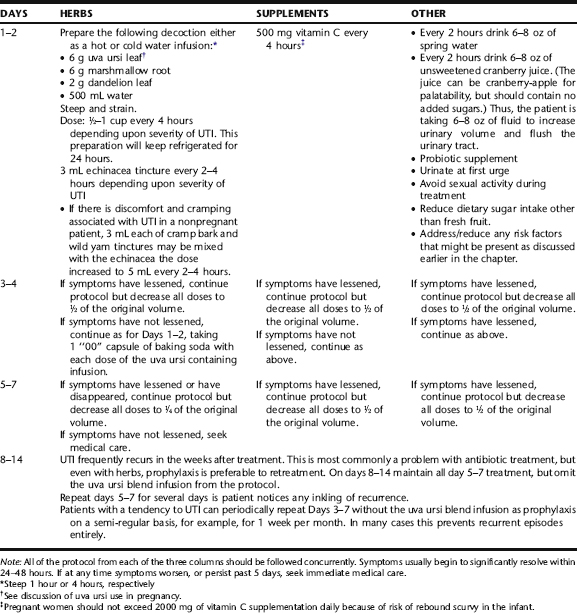

Botanical medicine provides an excellent alternative to antibiotic use for reducing the duration and symptoms of lower UTI, preventing progression to upper UTI, and preventing recurrence. Lower UTI in nonpregnant women is often easily treated with simple protocol. Because of the risks associated with untreated pyelonephritis, it is recommended that patients with upper UTI be referred for medical care, and that botanical interventions be used in the context of complementary care. Care of pregnant women requires specific expertise in midwifery or obstetrics, as well as knowledge of herbs that are contraindicated in pregnancy, and must be done in consultation with an obstetric care provider. This section provides guidelines for the treatment of uncomplicated cystitis (Table 9-1).

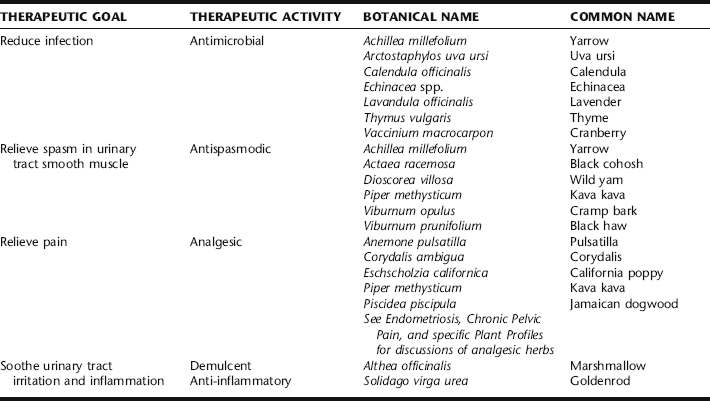

Botanical treatment of lower UTI incorporates the use of urinary antiseptic and antimicrobial herbs with demulcent herbs (Table 9-2). Additionally, a diuretic may be included to assist the body in its attempt to increase the delivery of fluids through the bladder. Herbs for cramping and aching may be included if needed. Herbs are used in the context of an overall protocol to increase fluids and diuresis, and to relieve offending lifestyle causes (e.g., chronic vulvovaginitis, overgrowth of uropathogenic bowel flora, or use of birth control methods or sexual habits that may contribute to the problem). Rarely UTI can lead to vaginal bleeding, sometimes quite copious. If this occurs seek medical care.

Calendula, Thyme, and Lavender

Calendula is typically used as a topical anti-inflammatory rinse with mild antimicrobial activity, either in the form of an infusion or diluted tincture, 1 tbs/125 mL water. Thyme and lavender are used topically for their antimicrobial activity and mild anti-inflammatory activity. in the form of peri-rinses for the treatment of urethritis associated with vulvo-vaginitis, and also for the reduction of rectal to urethral microbial spread. They can be used as infusions or the essential oils can be diluted in tea or warm water. Ingredients for a sample peri-rinse are provided in Table 9-1 (also see Chapter 3). Topical use of these herbs is considered safe during pregnancy.

Cranberry

The use of cranberries (Fig. 9-1) for the treatment of UTI dates back to the mid-nineteenth century when German chemists discovered that consumption of the berries produced a bacteriostatic acid in the urine. By 1900 in the United States, it was postulated that eating cranberries acidified the urine and prevented UTIs.7 This mechanism of action has been questioned as studies have failed to consistently show acidification of the urine with consumption of cranberry juice. There are mixed results regarding the effect of cranberry juice, fruit, and extract on urine pH. It appears that cranberry does not consistently lower urine pH and it is uncertain whether any reduction in urine pH that does occur has an antibacterial effect.8 However, the use of cranberry products continues to be a popular and empirically efficacious means of preventing and treating uncomplicated lower UTI. It is now accepted that the primary mechanism of action of cranberries is caused by two compounds in cranberries that each prevent fimbriated E. coli from adhering to uroepithelial cells in the urinary tract. 9 10 11 These compounds are also found in blueberries, which may also be used as part of the prevention and treatment of UTI.12 Although cranberry has primarily been used against uropathogenic E. coli, recent evidence from in vitro studies suggests that it may have activity against other uropathogenic organisms, and also against H. pylori, responsible for gastric ulcers.13 Cranberry also may prevent the formation of biofilms on epithelial mucosa, reservoirs of bacteria that are difficult to effectively treat with antibiotics.8

Based on a comprehensive review of the literature by the Cochrane Collaboration, there is some evidence from two good-quality RCTs that cranberry juice may decrease the number of symptomatic UTIs in women over a 12-month period. Based on the literature, there have been problems with noncompliance over long periods of administration, probably because of the taste of some cranberry products or possibly other side effects; and the optimum dosage and administration methods (e.g., juice or tablets) are unclear, necessitating further properly designed trials.14 However, clinical experience with cranberry juice products in herbal practice suggests that compliance problems can be overcome by using palatable products. In two good-quality RCTs, cranberry products significantly reduced the incidence of UTIs at 12 months compared with placebo/control in women. One trial gave 7.5 g cranberry concentrate daily (in 50 mL); the other

Topical Treatment for Urethritis

gave 1:30 concentrate given either in 250 mL juice or tablet form. There was no significant difference in the incidence of UTIs between cranberry juice vs. cranberry capsules.14 The safety of cranberries and their general healthful properties, along with combined empiric evidence of numerous practitioners, suggests that it is reasonable for women with no other significant health problems to use cranberry products for the prevention of recurrent UTI.15 A recent review article on cranberry summarizes that “recent, randomized controlled trials demonstrate evidence of cranberry’s utility in urinary tract infection prophylaxis. … Cranberry is a safe, well-tolerated herbal supplement that does not have significant drug interactions.”16 Recommended daily doses of cranberry for the prevention of UTI vary. Based on the available literature, the therapeutic dose of cranberry juice is 30 to 300 mL daily or three 8-oz glasses of unsweetened juice daily, or one tablet (300 to 400 mg) of cranberry extract tablets twice daily.8,16

Uva Ursi

Uva ursi (Fig. 9-2) is one of the most commonly used urinary tract disinfectants in modern herbal medicine.17 The leaves, taken as a cold or hot infusion, decoction, or tincture, are primarily used as an antiseptic in urinary tract infections.7 Uva ursi is commonly combined with urinary demulcents, such as marshmallow root or corn silk, and also may be taken with an herbal diuretic, most commonly dandelion leaf, but goldenrod or birch

leaf may be used as well. Diuretics are contraindicated in pregnancy. Cold infusion reduces the tannin content of the product, making it easier for the digestive system to handle and reducing the nausea sometimes associated with its use; however, cold preparations might be inadvisable for immunocompromised patients because of the potential for microbial contamination from the herbs. Uva ursi is approved by the German Commission E for the treatment of inflammatory conditions of the urinary tract.18 It is widely used in the treatment of uncomplicated acute and recurrent UTI, based on its astringent and antibacterial actions, and when antibiotics are not deemed essential.19 Midwives include the herb as an astringent anti-inflammatory in sitz baths and perineal rinses for postnatal perineal healing and as part of treatment of vaginitis and urethritis. Unfortunately, there are few clinical trials and pharmacodynamic studies of uva ursi. In vitro studies using crude leaf preparations and extracts of uva ursi leaf have demonstrated mild antimicrobial activity against known UTI-causing organisms including C. albicans, E. coli, S. aureus, and Proteus vulgaris, and others.20 Several studies have also demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity of the herb, particularly enhanced when extracts are used in combination with anti-inflammatory pharmaceutical drugs, such as prednisolone, indomethacin, or dexamethazone.21,22 One double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study of 57 women utilized a combination extract of hydroalcoholic extract of uva ursi leaves, standardized to an unknown amount of arbutin and methylarbutin uva ursi with dandelion leaf (Taraxacum officinalis) to evaluate the efficacy of this combination for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection. Inclusion in the study required that otherwise healthy individuals had suffered at least three episodes of cystitis in the past year and at least one episode in the last 6 months prior to this study. Patients received either the extract (n = 30) or placebo (n = 27) three tablets three times daily for 1 month and were then followed for 12 months. At the end of the 12-month monitoring period, significantly more women in the placebo group experienced recurrent cystitis compared with the treatment group (p < 0.05). No adverse effects were reported.17,23

Some amount of disagreement can be found in the literature regarding the requirement of an alkaline pH environment for the efficacy of this herb. Some authors postulate that a reduced urinary pH inhibits the efficacy of the herb; others argue that increasing the alkalinity of the urinary environment enhances the efficacy of the herb, while still others state that activity is not dependent on urinary pH. Given the reliability of this herb generally, it is prudent to conclude that if uva ursi does not seem to be working, the addition of four “00” capsules of the equivalent of 1 tablespoon sodium or potassium bicarbonate may be taken once or twice daily, divided between uva ursi doses, to alkalinize the urine in such situations before making a final determination about efficacy.15,19,24,25

The question of whether this herb is safe for use in pregnancy is difficult to definitely answer based on the available evidence. The Botanical Safety Handbook gives this herb a Class 2b and 2d rating: Not to be used in pregnancy, a caution that is reiterated by many authorities.17,18,26,27 However, the reasons for contraindication are variable and not well supported, ranging from alleged uterotonic and oxytocic activity to “theoretical fetotoxicity.”17,27 The original source of the concern of oxytocic activity appears to stem from Brinker, who reported that there is “empirical” evidence of oxytocic action with no further explanation.28 Low Dog states that the herb has potential fetotoxicity because of its hydroquinone content. Studies using pure hydroquinone (i.e., not the whole herb or whole herb products) have produced microtubulin dysfunction in bone marrow, and exposure of human lymphocytes and cell lines to hydroquinone has been shown to cause genetic damage.15 However, giving pure constituent is not the same as giving a whole herb, a perennial problem in assessing the safety of herbs with conventional pharmaceutical testing models. Although Tyler et al. state that mutagenicity may be associated with this herb, other researchers report on low potential for mutagenicity and negative Ames’ test.17 In animals administered 100 and 400 mg/kg per day of arbutin, no signs of fetal toxicity were observed.17 Uva ursi has been used by midwives as a mainstay treatment of acute symptomatic cystitis in pregnancy for over two decades in the United States with no adverse reports associated with its use.29 Empiric observation demonstrates less recurrence of UTI with uva ursi versus treatment with antibiotics. The transference to infants of arbutin/hydroquinone from uva ursi use during lactation has not been researched and therefore is not recommended by German authorities; however, the risk remains speculative.18 McKenna et al. recommend using only the lowest doses during lactation, observing the infant for side effects, and using under the guidance of a knowledgeable lactation expert.7 It is always prudent to avoid the medical use of herbs during the first trimester unless absolutely necessary. In the case of uva ursi, it is advisable to avoid it entirely during the first trimester, and to use it only if it is the best option for treatment of UTI later in pregnancy, using only at a minimal effective dose and for minimal duration. Further research in this area is clearly needed, particularly given the volume and frequency of UTIs among pregnant women.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree