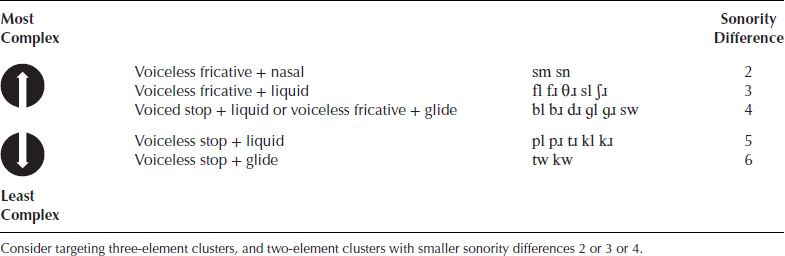

Chapter 8 Hollywood cameraman John Alton wrote the first book on cinematography in 1949, calling it Painting with Light. This title may have been the inspiration for The Publicity Photograph (Galton & Simpson, 1958), a radio sketch for Hancock’s Half Hour. Persuaded by Miss Pugh (Hattie Jacques), Bill (Bill Kerr) and Sid (Sid James) that he needs to update his image, Hancock (Tony Hancock) and Sid consult flamboyant theatrical photographer Hilary St. Clair (Kenneth Williams, he of the soaring triphthongs). When Sid tells St. Clair, ‘I want you to take some snaps’, he is outraged! ‘Snaps, Sidney? I don’t take snaps; I paint with light!’ The topic of ‘therapy tips’ often arises in social media discussions and at professional development events. When it does, there can be an urge to mount one’s high horse and emulate St. Clair’s retort. ‘Tips? Tips? I don’t do tips! I put solid theory and evidence into practice!’ or whatever the SLP/SLT equivalent of painting with light might be. But as seasoned interventionists know, therapy breakthroughs often come when, without abandoning evidence-based practice, we play educated clinical hunches, have a good idea, apply inspired brainwaves shared by mentors and colleagues, simply try something different, or implement a tip or trick from our repertoire that has worked for us before in making our jobs as scientific clinicians easier, especially with more complex clients. This chapter holds a compilation of such tips, tricks and insights, and pointers for where to find more. As shown in Boxes 6.1 and 6.4, points 7, 8, 9 and 10, there are four signs that may help us determine whether a child’s speech difficulties, or at least some of them, are phonological in nature. We should consider the possibility of phonological disorder and a phonological intervention approach if the puzzle phenomenon is evident, if there is a pattern of unusual errors, if the child is marking contrasts ‘oddly’, and if error sounds are readily stimulable. Two of these giveaway signs, the puzzle phenomenon and marking, can be difficult to ‘pick’ unless the clinician is actively looking for them, so examples are provided below. The puzzle phenomenon occurs when a child consistently mispronounces sounds where they should occur, but uses them as substitutes where they should not! A ‘demonstration’ by Dane, father of Quentin, 6;1, exemplifies this. Dane: Show her how you say thumb. Quentin: Fum. Dane: Now say sum. Quentin: Thum. Dane: If he can say thumb when he means sum, how come he says fum when he means thumb? I think he’s just lazy. A second example of the puzzle phenomenon comes from Andrew, 4;6. Some of the errors children make deceive our trained ears; but when we listen closely, we may find that the errors provide hints that a child knows more than he or she is able to produce, and that their difficulties are phonological and not phonetic. They do so by ‘marking’ the presence of the correct sound, with nasality and/or with vowel length. Uzzia, 5;1, with extensive final consonant deletion, talked about going to [bϵ](bed) and referred to her brother as [bϵ̃]. Although it was easy to hear these as homonyms, it was apparent that Uzzia was marking the presence of the /n/ in Ben by nasalising the preceding vowel. This hint of a nasal final consonant was consistent with what happens normally, in that vowels preceding nasal consonants are usually nasalised. Like Uzzia, Owen, 4;3, also exhibited final consonant deletion, producing bus as [bʌ] and Buzz Lightyear’s name as [bʌː], and again these two productions, [bʌ] and [bʌː], were readily mistaken for homonyms. But when we recall that vowels are typically longer before voiced consonants, we would be on safe ground to assume that Owen’s lengthening of the short vowel /ʌ/ to [ʌː] meant that he ‘knew’ the difference between /s/ and /z/ but was not yet able to produce them SFWF. Individualised Education Programs (IEPs) or Individualised Education Plans (IEPs) for articulation therapy tend to be along the lines of the following ones for Alison 7;1 who had /s/ as a phonetic target. These goals are based on those in the IEP Goal Bank provided at www.speakingofspeech.com/IEP_Goal_Bank.html#artic. Long-Term Goal: Alison will produce the /s/ speech sound with 90% mastery. Short-Term Objectives: Chapter 6 contains an exploration of the six-shared characteristics of phonological disorders and childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) (see Tables 6.1 and 6.4 and associated discussion) and 14 goals in common. The six characteristics are: (1) Consonant inventory constraints; vowel inventory constraints; phonotactic inventory constraints. (2) Omissions of consonants, vowels and syllable shapes that are already in the child’s inventory. (3) Vowel errors. (4) Altered suprasegmentals. (5) More errors with longer and/or more complex utterances, including the so-called ‘SODA’ errors of substitution, omission, distortion and addition. (6) Use of simple, but not complex, syllable shapes and word shapes. The 14-shared goals are: (1) Consonant inventory expansion. (2) Vowel inventory expansion. (3) Phonotactic inventory expansion. (4) Syllable shape inventory expansion. (5) Word shape inventory expansion. (6) Increased accuracy of production of target structures. (7) More complete vowel repertoire. (8) More accurate vowel production. (9) Production of strong and weak syllables. (10) Differentiation of strong and weak syllables. (11) Generalisation of new consonants and vowels, syllable structures, and word structures, to more challenging contexts. (12) More complete phonotactic repertoire. (13) More varied use of phonotactic range within syllables and words. (14) Improved accuracy. Clearly, when goal setting and writing IEPs for children with phonological disorder and/or CAS these 14 goals cannot be expressed in the same way articulation goals usually are, using ‘mastery’ criteria and percentages. So, what follows is a suggested guide for wording IEP goals, based on the six characteristics common to both diagnoses, and the 14 treatment goals in common. Then follow examples of IEPs that were used for Tad who had CAS in combination with significant phonological issues. Tad’s IEP goals encompassed 1, 2, 4 and 8 in the guide. Expanding the consonant inventory; promoting more accurate consonant production. Long-Term Goal: Tad will produce the stops /p b t d k ɡ/ and the fricatives /f s ʃ/ or close approximations in CV and VC syllable and word contexts. Short-Term Objectives Expanding the vowel inventory; promoting more accurate vowel production. Long-Term Goal: Tad will produce all vowels and diphthongs in CV and VC syllable and word contexts. Short-Term Objectives Expanding the word shape inventory; promoting more accurate word structures. Long-Term Goal: Tad will produce the clusters /pl bl kl and ɡl/ or close approximations in CCV and CCVC word contexts. Short-Term Objectives Promoting generalisation of accurate new: segments, syllable structures, word structures and prosodic features – to more challenging contexts. Long-Term Goal: Tad will produce segmentally correct trochaic sequences, with appropriate prosody (stress and intonation), in word and sentence contexts. Short-Term Objectives A tradition is a ritual, belief or object passed down within a society, maintained in the present, with origins in the past. A scientist embarking on a research trend inherits the tradition of preceding scientists, along with their conclusions and critical discussion. A sense of such a crucial inheritance of tradition is what sets apart the best scientists; those who change their fields through their embrasure [widening] of tradition. (Kuhn, 1977) In the left column of Table 8.1 is a list of eight familiar, traditional target selection criteria that are not strongly based, if at all, in evidence or solid theory. In the right column are eight newer criteria with stronger linguistic underpinnings and empirical support. The implication here is not ‘out with the old criteria, and in with the new(ish)’! We can combine all of these criteria to bring the evidence, theory and critical discussion of science, and the wisdom of tradition, to the same table while respecting the characteristics and preferences of the child, the family and the clinician, and the individual child’s intervention needs. Table 8.1 Traditional and newer criteria for treatment target selection Working on sound targets in the typical sequence of acquisition is done on the logical assumption that earlier developing sounds are easier for a child to learn first, less frustrating for them to attempt, or easier for the clinician to teach (Hodson, 2007, 2010; Van Riper & Irwin, 1958). A clinician using this strategy might prioritise intervention targets following Shriberg’s (1993) early, middle, and late eight acquired sounds, displayed in Table 1.2, proceeding from the early eight: /m n j b w d p h/ to the middle eight: /t ŋ k ɡ f v tʃ ʤ/ to the late eight: /ʃ ʒ l ɹ s z θ ð/, or they might refer to any number of ‘age of acquisition tables’ (McLeod, 2013) or ‘phonetic mastery tables’ (Kilminster & Laird, 1978, also displayed in Table 1.2), or Hodson’s (2007, 2010) target selection guidelines. The notion of ‘social importance’ usually implies a significant target for the child or parents in terms of how the child is perceived, and may relate to avoiding embarrassment, as in the following examples. Stoel-Gammon (A9) describes Brett, 4;9, who was teased for saying Bwett. Tired of the hilarity it generated, the Ayres family were anxious for Gerri, 5;3, to stop calling herself /dϵɹiϵːz/ (example used by permission); and Shaun, 4;9, was eager to work on /ʃ/ because he was taunted for saying his name /dɔn/. Many SLPs/SLTs have been asked by parents if the word truck might be considered as a target in children who pronounce /tɹ/ as in tree as /f/. Prioritising for intervention the child’s stimulable, most knowledge phonemes (see Table 8.4) is based on the interwoven ideas of developmental readiness, ease of learning, and early success as a motivator (Hodson, 2007, 2010) for the child, and ease of teaching (for the clinician). Traditionally, ‘stimulable’ has meant that a consonant or vowel can be produced in isolation by the child, in direct imitation of an auditory and visual model with or without instructions, cues, imagery, feedback, and encouragement. For example, a clinician might elicit /f/ simply by providing placement cues and modelling it. Meaningful minimal word-pairs, or real words contrasted with each other, can be maximally opposed, like sick-wick, which differs in place, voice, manner and major class (and markedness); ‘nearly maximally opposed’, like big-jig, which cuts across many featural dimensions but shares the voicing feature; or minimally opposed, like pat-bat differing in voice only, tip-sip differing in manner only, and cap-tap differing in place of articulation only. Targeting error phonemes, or error patterns, using minimally opposed words is done on the understanding that it is the most direct way of demonstrating (his or her own) homophony to a child (Dean, Howell, Waters & Reid, 1995; Grunwell, 1989). So, in choosing treatment words for a child exhibiting voiced velar fronting SFWF, word contrasts such as bug-bud, cog-cod, beg-bed and mug-mud would be selected, with just one feature difference (in place) between error and target. In the process of constructing minimal pair sets, the clinician would attempt to find phonetically appropriate picturable words representing age-appropriate vocabulary that lend themselves to activities for pre-readers, and in most instances would include printed captions, in lower case, on picture cards and worksheets. For example, peel would be printed ‘peel’, not ‘PEEL’ or ‘Peel’ and Paul would be printed ‘Paul’ not ‘PAUL’ or ‘paul’, to be consistent with the way early literacy instruction is commonly delivered. Note that a near minimal pair is formed with the addition or removal of a sound, or in other words, a change in syllable structure, as in lap-clap, blimp-limp, moat-most, and mild-mile. Bound morphemes used to mark inflection generate morphosyntactic minimal pairs (e.g., jumps-jumped, drags-dragged) and morphosyntactic near minimal pairs (e.g., book-books, run-runs). Choosing unfamiliar words or low-frequency words (in terms of their usage) for treatment stimuli is based on the premise that a child’s error production of seldom-spoken or novel words (like yowie, yeti, and yen) will not be as habituated as familiar words (such as yes, yell, you and yet), or well-established, frozen (fossilised) forms like /lϵloʊ/ for yellow. The principle governing the selection of sounds that are sometimes pronounced correctly is that, because the child demonstrates some knowledge of an inconsistently erred target, it will be easier to learn and teach than a sound for which a child has less (or no) knowledge. For example, following the developmental trend, a child receiving intervention might have acquired velar stops word finally in words like shake and big, but not in other syllable contexts, encouraging the clinician to target /k/ and /ɡ/ pre-vocalically, inter-vocalically, and in clusters, perhaps using facilitative contexts containing final velars (see Backward Chaining in Chapter 6). Similarly, a child might be producing the /k/ and /ɡ/ in /kl/ and /ɡl/ clusters but not in other positions, as can happen in typical acquisition, prompting the construction of near minimal pairs, such as clap-cap, clean-keen; glow-go, glad-lad, to facilitate velar stops SIWI. Again, a child may be able to produce the voiceless affricate only in words ending with /ntʃ/, suggesting that practising words such as those found here: www.speech-language-therapy.com/pdf/clustersNCHsfwf.pdf, might be facilitative. Sometimes an error has such a pervasive, negative impact on intelligibility that it compels consideration as a high treatment priority (Grunwell, 1989). My client Yoshi, 4;2, with English as his first language had a PCC below 30% in both Japanese and English. His mother’s second language was Japanese, English was his monolingual father’s only language, and his Japanese au pair communicated with him in Japanese and German. In English, Yoshi had widespread glottal insertion before and after utterances and pre- and post-vocalically (as in Japanese). This, coupled with a complete absence of voiced stops had a devastating effect on his intelligibility. Early treatment goals included achieving stimulability of /b d ɡ/ to two-syllable positions and elimination of glottal insertion. Yoshi’s phonology was unusual in there being no glottal replacement evident, only glottal insertion. Another client Sam, 4;1, had the unusual pattern of replacing stops with /f/ or /v/ which I saw only twice over 40 years of clinical practice, and had no clusters (e.g., boo → /vu/ blue → /vu/ Pooh → /fu/ do → /vu/ coo → /fu/ goo → /vu/). Note that Sam marked the voiced-voiceless cognate correspondences. The effect of these idiosyncratic errors meant that stops and clusters virtually had to be early targets for him. Flipsen Jr. and Parker (2008) drew upon Dodd and Iacono (1989), Edwards and Shriberg (1983) and Khan and Lewis (1983) to make lists of non-developmental and developmental patterns, based on the 1983 and 1989 authors’ interpretation of what was ‘developmental’ and what was not. Flipsen Jr. and Parker reported that the non-developmental patterns include: initial consonant deletion; within word consonant deletion (SIWW and SFWW); deletion of unmarked elements of clusters; within word consonant replacement (SIWW and SFWW); errors of insertion and addition (e.g., schwa insertion or addition; vowel addition word finally) and intrusive consonants; backing of stops, fricatives, and affricates; dena- salisation; devoicing of stops; idiosyncratic systematic sound preferences; and glottal replacement, unless it is dialectal. Developmental patterns include final consonant deletion; reduplication; weak syllable deletion; cluster reduction; context-sensitive voicing; depalatalisation; fronting of fricatives, affricates, and velars; alveolarisation of stops and fricatives; labialisation of stops; stopping of fricatives and affricates; gliding of fricatives and liquids; deaffrication; epenthesis; metathesis; migration; and vocalisation. Grunwell (1989) recommended that patterns that ‘deviated most from normal development’ (i.e., non-developmental phonological patterns) should be given priority as treatment targets, particularly initial consonant deletion, which is not attested in normal development in English, and glottal replacement where it is not dialectal. These non-developmental patterns often beg to be eliminated because they can sound ‘odd’ even to the untrained ear, and they can disrupt prosody and affect intelligibility. Non-developmental phonetic errors are also often given priority. These include lateral fricatives and affricates, ingressive fricatives, phoneme specific nasality and vowel errors. Prevalent or inconsistent vowel errors are a diagnostic marker for CAS. Children with CAS and those with moderate/severe phonological disorder frequently experience difficulties producing vowels (Gibbon, A29). Vowel errors may occur in as many as 50% of children with these diagnoses (Eisenson & Ogilvie, 1963; Pollock & Berni, 2003). Depending which study is consulted, 24%–65% typically developing children below 35 months have a high incidence of vowel errors. This is a wide range that it is difficult to interpret. A more meaningful, useful piece of information for clinicians’ guidance is that by 35 months errors are far less prevalent, ranging from zero to 4% (Pollock & Berni, 2003). Some research suggests selecting later developing sounds (e.g., the late eight acquired consonants: /ʃ ʒ l ɹ s z θ ð/ in Table 1.2), complex targets (e.g., the marked consonants from a choice of /p t k f v θ ð s z ʃ ʒ tʃ ʤ/ that are missing from the child’s inventory), and the more marked of the clusters: /spɹ/, /stɹ/, /skɹ/, /spl/ and /skw/, and /sm/, /sn/, /fl/, /fɹ/, /θɹ/, /sl/, /ʃɹ/, /bl/, /bɹ/, /dɹ/, /ɡl/, /ɡɹ/ and /sw/ (see points 10 and 14 below) as early treatment targets because training them will result in greater system-wide change (Gierut, Morrisette, Hughes & Rowland, 1996). Gierut and colleagues furnish persuasive arguments in favour of devising complex targets that are marked, non-stimulable, late acquired, consistently erred, and presented to the child in high-frequency words representing maximally distinct feature oppositions (Baker, A13). A distinctive feature, or ‘feature’, is an acoustic or articulatory parameter whose presence of absence defines a phonetic category, distinguishing it from another phonetic category (Chomsky & Halle, 1968). Targeting the marked properties (features) of phonemes is prioritised on the understanding that it may well facilitate acquisition of unmarked aspects of the system. Markedness is a concept from the study of the sound systems of all natural languages. A marked feature in a language implies the necessary presence of another feature, hence the term ‘implicational relationship’. There are languages, like English, that have stops and fricatives. There are languages that have stops, but no fricatives. But no language has fricatives and no stops. This means that fricatives are a marked class of sounds because the presence of fricatives necessarily implies the presence of stops in a particular language. Thus, it is said that there is an implicational relationship between the fricatives /f v θ ð s z ʃ ʒ/ and stops (Elbert, Dinnsen & Powell, 1984). Another way of putting this is to say that the fricatives, /f v θ ð s z ʃ ʒ/, are marked because they imply stops. Similarly, the voiceless stops that occur in /s/ clusters (/p t k/) are marked because they imply voiced stops: /b d ɡ/. Furthermore, according to this interesting but somewhat controversial body of research, consonants imply vowels (Robb, Bleile & Yee, 1999); affricates /tʃ and dʒ/ imply fricatives (Schmidt & Meyers, 1995); clusters (except for /sp, st, sk/) imply affricates (Gierut & O’Connor, 2002); and true clusters with small sonority differences imply true clusters with larger sonority differences (Gierut, 1999). David Ingram (personal correspondence, May 2011) notes that Jakobson discussed the voiceless stops /p/, /t/ and /k/ as unmarked, and that this is common in the linguistic literature. This general claim, however, is based on languages where the voiceless stops are unaspirated and have roughly a zero voice onset time (VOT). English speaking children start out with stops that are characterised by 0 VOT, but English speaking parents (including researchers) hear and often transcribe these as voiced because they are within the VOT boundaries for English voiced stops. So, the unmarked stop for English children is neither the English voiced nor voiceless aspirated stop, but those stops that occur after ‘s’ in clusters (i.e., /st/, /sp/ and /sk/). Based on judgements of accuracy, the voiced stops in English actually are acquired before the voiceless ones, and can be interpreted as the unmarked ones. Interestingly, the opposite occurs in Spanish where the voiceless stops are 0 VOT and the voiced stops are prevoiced. Spanish children start out doing well with voiceless stops, which are perceived by Spanish speakers as voiceless, and have errors with the voiced ones, sometimes making them fricatives, something rarely if ever seen in children with English as their first language (L1). So the markedness of stops has to be viewed in relation to whether a language has one, two or even three series of stops, and in relation to their VOT values. In summary then, some research suggests we should target the marked consonants and clusters, particularly those with small sonority differences (see point 14 below), to facilitate the acquisition of unmarked ones. Clinicians interested in applying these ideas in intervention can be guided as follows: Since the mid-1990s, sections of the research world have encouraged clinicians to target non-stimulable sounds because if a sound is stimulable, or if it becomes stimulable, it is likely to be added to a child’s inventory without direct treatment (Miccio, A23; Miccio, Elbert & Forrest, 1999). As sounds that are not stimulable have poorer short-term prognosis than those that are, treatment outcomes are likely to be enhanced when SLPs/SLTs use their unique skills to address the production of those non-stimulable sounds – to make them stimulable. Once the sounds are stimulable, in two-syllable positions (e.g., /f/ SIWI and SFWF in fie and off, respectively; or alternatively /f/ SIWI and SIWW in far and Sophie, respectively), they are likely to progress and become established in the child’s productive repertoire even if not targeted directly for treatment beyond that level. This has strong implications for clinicians who, for whatever reason, can only see a child with significant inventory constraints infrequently. The available time to provide intervention in such circumstances may be best spent doing stimulability therapy, something we are exclusively qualified to do, rather than expect an unskilled non-SLP/SLT, perhaps armed with a ‘home program’, to teach sounds absent from the child’s repertoire. Targeting stimulable sounds yields short-term but limited gains, in terms of generalisation (Powell & Miccio, 1996), whereas targeting non-stimulable sounds via stimulability therapy (Miccio, A23), exploratory sound play, and phonetic placement techniques increases the probability of generalisation, once stimulability has been achieved (Rvachew, Rafaat & Martin, 1999). Rvachew & Nowack (2001) determined that clinicians can be reasonably confident that provided the child has relatively greater productive phonological knowledge for them, that is, the child is stimulable for them, developmentally earlier targets will be easier for pre-schoolers to acquire than target phonemes that are both unstimulable and late developing. The rationale for using maximally opposed, non-proportional contrasts (Gierut, 1992) is that the heightened perceptual saliency of the contrasts so formed increases learnability, facilitating phonemic change. This is discussed under Maximal Oppositions and Empty Set in Chapter 4 with examples of treatment targets for Xing-Fu, 4;5, and Vaughan, 5;8, and elaborated by Baker (A13). A maximal opposition cuts across many featural dimensions. For example, by referring to the Table 2.5 and Table 8.2 we see that the contrast between /b/ and /s/ in the word pair bun-sun is in place (labial is distinct from coronal), manner (stop is distinct from fricative) and voice (/b/ is voiced and /s/ is voiceless). The contrast between /f/ and /n/ in fat-gnat is in place, manner, voice and major class (/f/ is an obstruent; /n/ is a sonorant). Table 8.2 ‘Place-Voice-Manner Chart’ for PVM Analysis, after Kleinschmidt, in Hanson 1983, pp. 132–133. Reproduced with permission from Elsevier Williams (A26; 2010) describes a non-traditional approach to target selection, based on analysis of the function of the sound in the child’s own system, as having maximal impact on phonological restructuring. This is explained with examples in Chapter 4 under the heading Minimal Pair Approaches: Multiple Oppositions, and by Williams herself in A26. Sonority is the amount of ‘sound’ or ‘stricture’ in a consonant or vowel, represented numerically in a ‘sonority hierarchy’ devised by Steriade (1990). Steriade’s proposed hierarchy was from most to least sonorous: vowels (=0) were most sonorous, followed by glides (=1), liquids (=2), nasals (=3), voiced fricatives (=4), voiceless fricatives (=5), voiced stops (=6) and finally voiceless stops (=7), the least sonorous. Markedness data tell us that consonant clusters are more marked than singletons (see point 10 above). Sonority theory adds to the picture by ranking two-element consonant clusters (note: just the two-element ones) in terms of markedness according to their sonority difference scores (Ohala, 1999), as displayed in Table 8.3. Table 8.3 Sonority Difference Scores For example, /kl/ (7 minus 1 in Steriade’s hierarchy) has a sonority difference score of 6, whereas /fɹ/ (5 minus 2) scores 3. As Baker (A13) discusses, small sonority differences of 3 (like /sl/ and /ʃɹ/) or 4 (like /ɡl/), and the three-element clusters may promote generalised change to singletons and clusters (Gierut, 1999; Gierut & Champion, 2001; Morrisette, Farris & Gierut, 2006) than other two-element clusters. It should be noted again here that Morrisette et al. (2006) count initial /s/ + stop ‘clusters’ as adjuncts and not ‘true clusters’. Some research suggests selecting sounds for which the child has ‘least knowledge’ in terms of the ‘knowledge types’ described in Table 8.4, because they will be easier to learn (Barlow & Gierut, 2002; Gierut, 2001; Williams, 1991). Applying learnability theory, Gierut (2007) provides support for the position that, in order for efficient learning to occur, we should teach phonologically impaired children complex aspects of the target system, outside of what they have learned already. Table 8.4 Knowledge Types. Reproduced with permission from the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association We can consider word properties when we choose words to use in intervention. In this respect we have the choice of selecting words that are either of ‘high frequency’ in the language, or words with ‘low neighbourhood density’. High-frequency words are those words that occur often in the language. They are recognised (comprehended) faster by children than low-frequency words. High neighbourhood density words are phonetically similar to many other words. Children recognise and repeat high-density words slower and with less accuracy than low-density words. As well, children name high-density words more accurately than low-density words, suggesting that lexical processing in children entails a high-density disadvantage in recognition and a high-density advantage in production (Storkel, Armbruster & Hogan, 2006). In view of this, in choosing stimulus words, or ‘treatment words’, the clinician might consider those that are either high frequency or have low neighbourhood density (Storkel & Morrisette, 2002).

Treatment targets and strategies for speech sound disorders

Phonological disorder signs

Puzzle phenomenon

yellow

/lϵloʊ/

brother

/bwʌzə/

then

/dϵn/

globe

/bloʊb/

those

/doʊz/

rabbit

/bɹæbɪt/

glove

/gwʌb/

some

/θʌm/

breathe

/bwiv/

thumb

/sʌm/

snooze

/ðuð/

zoo

/ðu/

Marking

Marking with nasality

Marking with vowel length

Individualised education programs: IEPs

Guide to expressing IEP goals phonological disorder and CAS

Tad’s IEP goals

Target selection

Traditional selection criteria Associated with: little or no evidence, logic, intuition, experience, hunches

Newer selection criteria These tend to be evidence-based, linguistically driven, theoretically sound

1. Work in developmental sequence

2. Choose socially important targets

3. Work on phonemes that are stimulable

4. Use minimal feature contrasts in treatment

5. Choose unfamiliar words as targets

6. Work on inconsistently erred sounds

7. Target sounds most destructive of intelligibility

8. Target non-developmental errors

9. Work on later developing sounds/structures first

10. Work on marked consonants first

11. Work on non-stimulable phonemes first

12. Use maximal feature contrasts in treatment

13. Use a systemic approach to analyse the child’s rules

14. Apply the sonority sequencing principle

15. Prioritise least knowledge sounds in treatment

16. Consider lexical properties of ‘therapy words’

Traditional target selection criteria

1. Work in developmental sequence

2. Choose socially important targets

3. Work on phonemes that are stimulable

4. Use minimal feature contrasts in treatment

5. Choose unfamiliar words as targets

6. Work on inconsistently erred sounds

7. Target sounds most destructive of intelligibility

8. Target non-developmental errors

Newer target selection criteria

9. Work on later developing sounds and structures first

10. Work on marked consonants first

11. Work on non-stimulable phonemes first

12. Use maximal feature contrasts in treatment

English Phonemes

Place

Labial

Coronal

Dorsal

Manner

NOTE cognate pairs:

voiceless on the left

Bilabial

Labiodental

Interdental

Alveolar

Palato-alveolar

Palatal

Velar

Glottal

Obstruents

Stop

p b

t d

k ɡ

Ɂ

Fricative

f v

θ ð

s z

ʃ ʒ

h

Affricate

ʧ ʤ

Sonorants

Nasal

m

n

ŋ

Liquid

l

ɹ

Glide

w

j

w

13. Use a systemic approach to analyse the child’s rules

14. Apply the sonority sequencing principle

15. Prioritise least knowledge sounds in treatment

Description

Examples

Type-1 knowledge – Most knowledge

A child displaying type-1 knowledge of target [s] would produce this sound correctly in all word positions and for all morphemes; [s] would never be produced incorrectly.

sun /sʌn/

soup /sup/

messy /mesi/

missing /mɪsɪŋ/

miss /mɪs/

Type-2 knowledge

A child displaying type-2 knowledge of target [s] would produce this sound correctly for all morphemes and positions. However, a phonological rule would apply to account for observed alternations between, for example, [s] and [t] in morpheme final position.

sun /sʌn/

soup /sup/

messy /mesi/

ice /aɪs/

BUT

miss /mɪt/

kiss /kɪt/

Type-3 knowledge

A child displaying type-3 knowledge of target [s] would produce this sound would produce this sound correctly in all positions. However, certain morphemes that were presumably acquired early and acquired incorrectly ‘fossilised’ would always be produced in error.

sun /sʌn/

messy /mesi/

miss /mɪs/

BUT

Santa /næ̃ntə/

juice /wu/

Type-4 knowledge

A child displaying type-4 knowledge of target [s] would produce this sound for all morphemes, in, for example, initial position. However, production of [s] would be incorrect in within-word and word final positions.

sun /sʌn/ soup /sup/

BUT

messy /meti/

missing /mɪtɪŋ/

miss /mɪt/

kiss /kɪt/

Type-5 knowledge

A child displaying type-5 knowledge of target [s] would produce this sound correctly in, for example, initial position. However, only some morphemes in this position would be produced correctly. All [s] morphemes in post-vocalic positions would be produced incorrectly.

sun /sʌn/

soup /sup/

BUT

soap /təup/

sock /sɔk/

messy /meti/

kiss /kɪt/

Type-6 knowledge – Least knowledge

A child displaying type-6 knowledge of target [s] would produce this sound incorrectly in all word positions and for all morphemes; [s] would never be produced correctly.

sun /tʌn/

soup /tup/

missing /mɪtɪŋ/

miss /mɪt/

kiss /kɪt/

16. Consider the lexical properties of ‘therapy words’

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree