Figure 5.1 The lymphatic drainage of the vulva initially flows to the superficial inguinal nodes and then to the deep femoral and iliac groups. Drainage from midline structures may flow directly beneath the symphysis to the pelvic nodes. Source: Modified from DiSaia PJ, Creasman WT, Rich WM. An alternative approach to early cancer of the vulva. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;133:825.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

KEY POINTS

- Vulvar cancer is more common in menopausal women.

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) is found in 55% to 60% of invasive tumors.

- All suspicious lesions should be biopsied in the office.

- Vulvar dystrophies may be precursor lesions of invasive disease.

Most vulvar cancers occur in postmenopausal women, although more recent reports suggest a trend toward younger age at diagnosis. Risk factors for vulvar cancer include a history of genital condylomata, a previously abnormal Papanicolaou smear, a history of smoking, and chronic immunosuppression. Both chronic vulvar inflammatory lesions, such as vulvar dystrophy or lichen sclerosus, and squamous intraepithelial lesions, particularly carcinoma in situ, have been suggested as precursors of invasive squamous cancers.

HPV DNA has been isolated from both invasive and carcinoma in situ lesions, with HPV type 16 being the most common subtype. Insinga and colleagues have reported that HPV DNA can be identified in approximately 80% to 90% of intraepithelial lesions, and 50% to 60% of invasive lesions. The rising incidence of HPV-related vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) among young women may explain the trend toward younger age at diagnosis of invasive vulvar cancers. Other infectious agents that have been proposed as possible etiologic agents in vulvar carcinoma include granulomatous infections and herpes simplex virus.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Most women with vulvar cancer present with pruritus and a recognizable lesion. Optimal management for any patient presenting with a suspicious lesion is to proceed directly to biopsy under local analgesia. Tissue biopsies should include the cutaneous lesion in question and contiguous underlying stroma so that the presence and depth of invasion can be accurately assessed. The goals of immediate evaluation with outpatient biopsy are to avoid delay in the planning of appropriate therapy. The presentation in advanced disease is generally dominated by local pain, bleeding, and surface drainage from the tumor.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Initial evaluation should include a detailed physical examination with measurements of the primary tumor, assessment for extension to adjacent mucosal or bony structures, and possible involvement of the inguinal lymph nodes. Because neoplasia of the female genital tract is often multifocal, evaluation of the vagina and cervix—including cervical cytologic screening—should always be performed in women with vulvar neoplasms. Fine needle aspiration biopsy from sites of suspected metastases may eliminate the need for surgical exploration in some patients with advanced tumors.

STAGING SYSTEMS

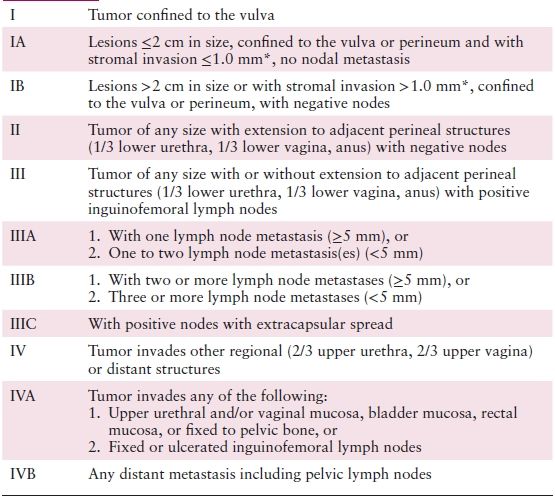

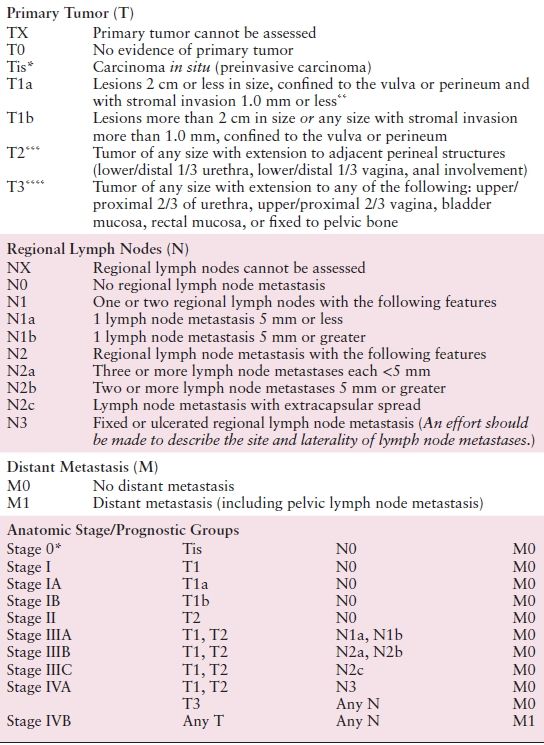

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) adopted a modified surgical staging system for vulvar cancer in 1989, which was most recently modified in 2009 (Table 5.1). The TNM classification scheme is correlated with the updated FIGO staging system (Table 5.2). Nodal status is determined by the surgical evaluation of the groin. The presence or absence of distant metastases is based on an unspecified diagnostic workup tailored to the patient’s clinical presentation.

Table 5.1 FIGO Staging of Carcinoma of the Vulva (Updated 2009)

* The depth of invasion is defined as the measurement of the tumor from the epithelial–stromal junction of the adjacent most superficial dermal papilla to the deepest point of invasion.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;105:103–104.

Table 5.2 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Staging of Vulvar Cancer (7th Edition)

* FIGO no longer includes Stage 0 (Tis).

** The depth of invasion is defined as the measurement of the tumor from the epithelial–stromal junction of the adjacent most superficial dermal papilla to the deepest point of invasion.

*** FIGO uses the classification T2/T3. This is defined as T2 in TNM.

**** FIGO uses the classification T4. This is defined as T3 in TNM.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Byrd SB, Compton DR, Fritz CC, et al., eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual Edge, 7th ed.; New York, NY: Springer, 2010:383–384.

PATTERNS OF SPREAD

Vulvar cancers metastasize in three ways: (i) local growth and extension into adjacent organs; (ii) lymphatic embolization to regional lymph nodes in the groin; and (iii) hematogenous dissemination to distant sites. Descriptive definitions of local extension are clinically useful in that local surgical resection with a wide margin is almost universally feasible in women with T1 or T2 tumors, occasionally possible in those with T3 lesions and impossible in those with T4 tumors without resorting to an exenterative operation. More recent experience with intraoperative mapping has demonstrated that lymphatic drainage from most vulvar sites proceeds initially to a “sentinel” node located within the superficial inguinal group.

Inguinal node metastasis can be predicted by the presence of certain parameters, including lesion diameter greater than 2 cm, poor differentiation, increasing depth of stromal invasion, and invasion of lymphovascular spaces. Clinically important observations regarding nodal metastases include the following: (i) the superficial inguinal nodes are the most frequent site of lymphatic metastasis; (ii) in-transit metastases within the vulvar skin are exceedingly rare, suggesting that most initial lymphatic metastases represent embolic phenomena; (iii) metastasis to the contralateral groin or deep pelvic nodes is unusual in the absence of ipsilateral groin metastases; and (iv) nodal involvement generally proceeds in a stepwise fashion from the superficial inguinal to the deep inguinal and then to the pelvic nodes. Spread beyond the inguinal lymph nodes is considered distant metastasis.

PATHOLOGY

KEY POINTS

- Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common histologic subtype.

- Melanoma is the second most common subtype, and 25% may be nonpigmented.

- The risk of lymph node metastases is negligible when the depth of invasion is less than or equal to 1 mm.

- Paget disease of the vulva has a high likelihood of recurrence and may be associated with underlying adenocarcinoma.

Most vulvar squamous carcinomas arise within areas of epithelium involved by some recognized epithelial cell abnormality. Approximately 60% of cases have adjacent VIN. In cases of superficially invasive squamous carcinoma of the vulva, the frequency of adjacent VIN approaches 85%. Lichen sclerosus, usually with associated squamous cell hyperplasia, and/or VIN, can be found adjacent to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma in 15% to 40% of the cases.

Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma precursors can be considered in two distinct groups: those associated with HPV, usually associated VIN, and those that are not (e.g., those associated with lichen sclerosus, chronic granulomatous disease).

Vulvar Carcinomas

Squamous Cell Carcinomas

The term microinvasive carcinoma is not recognized as meaningful in reference to the vulva because there are no commonly agreed upon pathologic criteria established for this term. However, a substage of FIGO stage I, stage IA, is defined as a solitary squamous carcinoma of the vulva measuring 2 cm or less in diameter with clinically negative nodes, with depth of tumor invasion 1 mm or less. Tumors with a depth or thickness of 1 mm or less carry little or no risk of lymph node metastasis. Stage I squamous carcinomas of the vulva, with a reported depth or thickness of 5 mm or more, have a lymph node metastasis rate of 15% or higher. In addition to tumor stage and depth or thickness, other pathologic features include lymphovascular space invasion, growth pattern of the tumor, grade of the tumor, and tumor type.

In a multivariable retrospective analysis of 39 cases of vulvar squamous carcinoma, in addition to clinical stage, and when corrected for treatment modality, pattern of tumor invasion, depth of tumor invasion, and lymph node status were all found to be significant prognostic factors. In addition, desmoplasia (a fibroblastic stromal tumor response) has been correlated with a higher risk of lymph node metastasis and poorer survival.

Verrucous carcinoma of the vulva is an exophytic-appearing growth that can be locally destructive. Clinically, it may resemble condyloma acuminatum. Because of its excellent prognosis, strict histologic criteria should be used in the diagnosis of verrucous carcinoma. Verrucous tumors may be associated with HPV type 6 or its variants.

Adenocarcinoma and Carcinoma of Bartholin Gland

Most primary adenocarcinomas of the vulva arise within Bartholin glands. Invasive vulvar Paget disease has been associated with underlying adenocarcinoma. Primary malignant tumors arising within Bartholin glands include adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, which occur with approximately equal frequency. Carcinoma of Bartholin glands generally occurs in older women and is rare in women younger than 50. In clinical practice, it is generally advisable to excise an enlarged Bartholin gland in a woman 50 years of age or older, especially if there is no known history of prior Bartholin cyst. If a cyst is drained and a palpable mass persists, excision is also indicated.

Primary carcinomas within Bartholin glands are characteristically deep in location and difficult to detect in their early growth. Approximately 20% of women with primary carcinoma of Bartholin glands have metastatic tumor to the inguinofemoral lymph nodes at the time of primary tumor diagnosis.

Vulvar Paget Disease and Paget-Like Lesions

Vulvar Paget disease typically presents as an eczematoid, red, weeping area on the vulva, often localized to the labia majora, perineal body, clitoral area, or other sites. This disease typically occurs in older, postmenopausal Caucasian women and may be associated with an underlying primary adenocarcinoma. Invasive Paget disease 1 mm or less in depth of invasion has reportedly little risk for recurrence.

Vulvar Malignant Melanoma

Malignant melanoma of the vulva accounts for approximately 9% of all primary malignant neoplasms on the vulva, and vulvar melanoma accounts for approximately 3% of all melanomas in women. This tumor occurs predominantly in Caucasian women, and the mean age at diagnosis is 55 years. Although usually pigmented, approximately one fourth are nonpigmented, amelanotic melanomas.

The level of invasion and tumor thickness are essential measurements in evaluating malignant melanoma. Malignant melanomas that have a thickness of less than 0.75 mm have little or no risk for metastasis and tumors up to 1 mm in thickness are generally considered to have minimal risk of recurrence. Melanomas of 1.49 mm thickness or less also correlate with good prognosis. A poor prognosis is correlated with thickness greater than 2 mm, or mitotic count exceeding 10/mm2. Other poor prognostic factors include minimal or nil inflammatory reaction and surface ulceration.

Metastatic Tumors to the Vulva

Most metastatic tumors to the vulva involve the labia majora or Bartholin glands. Metastatic tumors account for approximately 8% of all vulvar tumors, and in approximately one half of the cases, the primary tumor is in the lower genital tract, including the cervix, vagina, endometrium, and ovary. In approximately 10% of the cases, the primary site of the metastatic tumor cannot be identified.

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

Prognosis has been most extensively evaluated in women with SCC. The major prognostic factors in vulvar cancer—tumor diameter, depth of tumor invasion, nodal spread, and distant metastasis—have been incorporated into the current FIGO staging system. Risk of local recurrence, although clearly associated with tumor size and extent, is also related to the adequacy of the surgical resection margins. Several retrospective studies have confirmed an increased incidence of local recurrence in patients with microscopic margins less than 8 mm in formalin-fixed tissue specimens.

The single most important prognostic factor in women with vulvar cancer is metastasis to the inguinal lymph nodes, and most recurrences will occur within 2 years of primary treatment. The presence of inguinal node metastases portends a 50% reduction in long-term survival. Because the clinical prediction of lymph node spread is inaccurate, node status is best determined via surgical biopsy. Prognostic issues that appear to be important in evaluating lymphatic involvement are (i) whether nodal spread is bilateral or unilateral, (ii) the number of positive nodes, (iii) the volume of tumor in the metastasis, and (iv) the level of the metastatic disease. Multiple positive nodes, bilateral metastases, involvement beyond the groin, and bulky disease are associated with poor prognosis.

TREATMENT

KEY POINTS

- Treatment should be individualized based on lesion location.

- Partial radical vulvectomy with inguinal lymphadenectomy through separate incisions is the treatment of choice for stage IB and some stage II tumors.

- Combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy is indicated for more advanced lesions and those that involve vital structures where primary resection would be morbid.

- Postoperative inguinal and pelvic irradiations are indicated for most patients with positive nodes.

The development of the radical vulvectomy with bilateral inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy during the 1940s and 1950s was a dramatic improvement over prior surgical options and greatly enhanced survival, particularly for women with smaller tumors and negative lymph nodes. Long-term survival of 85% to 90% can now be routinely obtained with radical surgery. However, radical surgery can be associated with postoperative complications such as disfigurement, wound breakdown, and lymphedema.

More recently, surgical emphasis has evolved to an individualized approach for tumors at either end of the spectrum. Many gynecologic oncologists believe that smaller vulvar tumors can be acceptably managed by less radical surgical approaches and have proposed more limited resections for certain subsets considered to represent early or low-risk disease. The obvious advantages of such an approach are retention of a significant portion of the uninvolved vulva, less operative morbidity, and fewer late complications. In contrast, radical surgery is frequently ineffective in curing patients with bulky tumors or positive groin nodes. Multimodality programs that incorporate radiation, surgery, and chemotherapy are now being investigated in women with these high-risk tumors based upon success with similar approaches in women with squamous cancers of the cervix.

Early Tumors

Tumors demonstrating early invasion of the vulvar stroma (≤1 mm) have minimal risk for lymphatic dissemination. Excisional procedures that incorporate a 1-cm unfixed normal tissue margin are likely to provide a curative result. Patients in this category represent the only subset for whom evaluation of the groin lymph nodes is unnecessary. After primary therapy, these patients should undergo frequent follow-up examinations.

Stage I and II Cancers

Traditional management of stage I and II vulvar cancers has been radical vulvectomy with bilateral inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. The operation removes the primary tumor with a wide margin of normal skin, along with the remaining vulva, dermal lymphatics, and regional nodes. This approach provides excellent long-term survival and local control in approximately 90% of patients. Disadvantages of radical surgery include the loss of normal vulvar tissue with alterations in appearance and sexual function, a 50% incidence of wound breakdown, a 30% incidence of groin complications (breakdown, lymphocyst, and lymphangitis), and a 10% to 15% incidence of lower extremity lymphedema. Additional postoperative therapy, primarily irradiation, should be considered in the 10% to 20% of patients with positive nodes with the understanding that this will further increase the incidence of lymphedema.

In an effort to reduce morbidity and enhance psychosexual recovery, several groups have espoused a more limited surgical approach for women with small vulvar cancers. The most frequent recommendation is to resect the primary lesion with a 1- to 2-cm margin of normal tissue and to carry the dissection to the deep perineal fascia. This partial radical vulvectomy should not be confused with the concept of excisional biopsy, which is used primarily as a diagnostic procedure.

Limited resection of the primary tumor is combined with a more conservative surgical approach to the groin, in which the ipsilateral groin nodes are used as the sentinel group for lymphatic metastases. Bilateral dissections are performed in patients whose tumors encroach on midline structures (within 1 cm of midline or involvement of midline structures such as the clitoris or perineal body). In patients with negative inguinal nodes, no further dissection or postoperative therapy is used. Patients with positive nodes can undergo additional nodal dissection of the contralateral groin or be treated with postoperative irradiation, or both. Patients with deep lymphadenectomy followed by irradiation have the greatest likelihood of lymphedema.

With limited resection, survival of 90% or better is attainable for patients with stage I vulva carcinoma with acceptable anatomic appearance and function. In an attempt to reduce treatment-related morbidity, the classic radical operation has been replaced by the use of “triple incision” techniques that separate the vulvectomy incision from the groin incisions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree