6 The Team

In this chapter we focus on the development and structure of teams, a major feature of the care that is provided to children with life-threatening illnesses and their families. We do so with the caveat that the literature on teamwork in pediatric palliative care is rather limited.2,3 Conspicuously absent are systematic empirical studies of how teams develop and operate and their effects on team members, patients, families, institutions, and communities.4,5 The literature that does exist is descriptive and of varying depth and breadth.4 Articles that deal with teams focus on the educational background of professionals who make up the team, their roles, and responsibilities.6 With few exceptions little attention is given to team development, team functioning, and team support in the face of serious illness and death.7–10 The purpose of this chapter is to draw attention to these issues in order to enhance our understanding of the team’s role in the care of children with life-threatening illnesses and determine what is needed to ensure the highest quality of care. Also, we hope to point the way toward further research and training.

Our discussion and recommendations are rooted in a relationship-centered approach that focuses on relationships among children, adolescents, and families who receive care services, and professionals who offer them. Such an approach recognizes the reciprocal influence between children and families on the one hand, and professionals, teams, and organizations on the other. These professionals, affected by their interactions, seek creative ways to contain, reduce, or transform suffering, and in so doing enhance the quality of care for a child who may never grow into adulthood.9,11,12 In other words, the relationship-centered approach is concerned with the establishment of relations that are potentially enriching, and are rewarding for all involved. Achievement of this goal requires understanding not only the patient’s and family’s subjective views and experiences so as to provide them with appropriate care, but also the professionals’ and team’s subjectivity, which shapes interactions with children and parents, and affects the quality of services.

Team Development

A dynamic, non-linear process

For a group of people to become a team they must share a common purpose, be strongly committed to the achievement of specific tasks, and value teamwork through which they expect to accomplish more by cooperating. Setting a clear task that is owned by each member and sharing outcomes are central to the transition from a group to a team.13

Another characteristic that distinguishes groups from teams is their size and leadership.13 While groups vary in size, teams contain no more than a few members who share leadership in clinical practice, although at an administrative level they are led by a senior member. Depending on a child’s condition and family’s situation, for example, different professionals may take the lead at any time and make a special contribution in order to achieve the team’s goal and tasks. Regardless of whether the team uses a manager to facilitate the coordination of actions or it chooses to be self-managed, the importance is that responsibility for outcomes be shared. By contrast, in a group, leadership is assigned to one person who imposes his or her leadership style that usually remains unchanged despite the changing focus or work activity.14

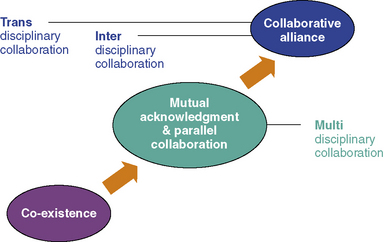

Among the available models for understanding team development, and especially applicable to palliative care, are those proposed by Papadatou and Morasz.9,15 They take the position that over the course of development, team members experience periods of co-existence, mutual acknowledgment and parallel collaboration, and of collaborative alliance with concomitant changes in disciplinary boundaries7,9,15,16 (Fig. 6-1).

Fig. 6-1 Dynamics of Team Development.

Redrawn from Papadatou, D. In the Face of Death: Professionals Who Care for the Dying and the Bereaved, New York, Springer Publishing; 2009.)

For a collaborative alliance to develop, care providers must spend time working together, sharing experiences, exploring different points of views, and developing a common language that does not exclude any member. Interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary teamwork require interdependent collaboration and are possible only if the team functions as an open system that makes use of relevant information. Relevant information is any information that helps members to understand how they operate as a system, how they manage suffering and adversities, and how they make use of their resources.9,17 Such information helps team members learn from experience, consider alternative ideas and coping patterns, embrace new initiatives, take risks, implement changes, and grow as a team. Unless there is opportunity to share information about what is happening in the day-to-day work, how things are accomplished, and how professionals think, feel and behave, team members cannot be in control of the quality of services they provide, and the system cannot be self-correcting.18 Such openness is not simply limited to the disclosure and airing of feelings and thoughts, but demands a reflective openness that enables team members to challenge their own and others’ thinking, suspend a sense of certainty, and share experiences with a receptiveness to having them challenged or changed.16,19

Organizational culture and context

A team’s development is not solely determined by its members.9,20 The social and organizational context in which it provides services has a major impact on how it develops and functions. For example, in some places pediatric palliative care services are delivered by teams in the community through home, respite, or hospice programs.21–24 In others, they are introduced in the hospital and offer consultation services to professionals, families, and other teams.4,25 In many countries that lack resources or are reluctant to acknowledge the needs of dying children and grieving families, palliative care teams are either non-existent or encounter major social, institutional, and legal obstacles in the provision of interdisciplinary services. Even in resource-rich countries that acknowledge the needs of dying children and grieving families, provision of interdisciplinary and palliative care services may be hampered by the country’s healthcare system.

Teams at Work

Indicators of team development, functionality, and effectiveness

We take the position that teams are active and dynamic systems with potential to change, develop, and grow. Teams, like the individuals who compose them, are not passive agents. Teams, like their members, are active agents who both shape and are shaped by their individual and collective responses to life-threatening illnesses, loss, suffering, and those whom they encounter in their work. Teams, like their members, are both subject to and react to internal and external stressors associated with the care of seriously ill patients and their families. Affected by the wider social and organizational context of work, team members, consciously or unconsciously, decide how to operate and collaborate with each other in order to meet the challenges of life-and-death situations. The team’s development, functionality and effectiveness are reflected in the patterns by which its members manage team boundaries and team operations as well as suffering and time.9

Experience and Management of Time

When a child’s life is threatened by a serious condition, time is perceived and experienced in unique ways by families and by care providers.26 A team that paces its work encourages children and their families not only to reflect on and work through their grief, but also to live a life that is meaningful to them. Such a team also takes the time to process work-related experiences that evoke anxiety in team members. The team learns from the past, integrates knowledge into the present practice, and strives toward future goals that aim at increasing the quality of the services it provides. In contrast, teams that avoid difficult subjects and experiences stagnate. Those teams become unable to take action, make decisions, and effect interventions. They delve into apathy and inertia. They become frozen in time. Some teams act as if time could be eliminated. They do too much; perhaps to avoid difficult issues such as case overload, loss, or death. Time is experienced as event-full. Work is driven by events or crises. An ongoing over-agitation prevents the team from slowing down in order to process its experiences and use relevant information for learning, changing, and growing.9,17

Teams and Families

A partnership in care

Most parents want to assume a central and active role in the care of their ill child. They acquire in-depth knowledge of the child’s condition and treatments, and develop appropriate skills in order to meet their complex needs.27,28 Parents of seriously ill children are faced with challenges and crises that are different from anything they have ever encountered in their lives.27 In their desire to be effective in this new parenting role, they have to interact with the professionals who can help them develop strategies and skills in order to manage present situations and anticipate future needs in both their sick and healthy children.27,28 This close involvement often leads to the erroneous assumption that parents are members of the team. Contrary to some clinicians who have written about teams and palliative care, we take the position that parents and patients are not members of the team.8,29

In this partnership, children’s views, concerns, and desires must be considered and approached with sensitivity and skill. This requires awareness of the differences in the ways children express both directly and symbolically, their physical, psychosocial and spiritual needs, preferences, and concerns; children and parents’ positions in the family; the rights, duties, and obligations each has to the other; and the impact of team’s actions on the patient’s and parents’ futures.30

Teams that experience difficulties with various aspects of boundary maintenance, goal setting, or time management are more likely to establish enmeshed or avoidant relationships with the patient and family.9 An enmeshed relationship develops when both the team and the family are unable to contain suffering, as well as the threat or reality of death. They become one, and remain undifferentiated, sometimes even after the child’s cure or death. For example, a team may need families that adore and glorify it, while at the same time some families need the team to maintain the memory of their deceased child to avoid moving on with life. An avoidant relationship between a team and a family, on the other hand, transforms their partnership into a strictly bureaucratic affair, a consumer-provider business that aims to manage practical issues without addressing the emotional and spiritual aspects of living with a life-threatening illness. Avoidant or enmeshed relationships are often reflective of the team’s and family’s inability to effectively manage the challenges of living with or dying from a life-threatening illness.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree