Fig. 35.1

Contemporary simulation mannequin

Principles of Simulation-Based Training for Pediatric Sedation

Initial Training

Approaches to the development of simulation-based training for pediatric sedation are not fundamentally different than training for other competencies. There are some obvious prerequisites. In most cases some experience in pediatric care is required as well as certification in Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS). Training is typically preceded by theoretical preparations using didactic presentations and self-learning of material, which includes important topics in pediatric sedation: patient evaluation and preparation, pharmacology, physiologic monitoring, protocols, policies, and regulations.

Simulation-based training is usually a tiered evolution of skill acquisition. This begins with the acquisition of task-specific skills relevant to pediatric sedation. This encompasses proficiency in essential rescue measures such as head positioning and suctioning, oxygen supplementation, bag-mask ventilation, and recovery positions. It can include the appropriate use of pharmacologic reversal agents and the proper use and interpretation of physiologic monitoring technologies including pulse oximetry and capnography. The skill training is best when individualized and will serve to achieve a common foundation of knowledge and language for trainees from various disciplines and backgrounds. Often these skills are taught by demonstration and practice on mannequins during short sessions with an instructor.

After acquiring basic sedation skills, the next “tier” of training progresses to “real-life” sedation scenarios that challenge multiple members of the team. These scenarios require the application, practice, and integration of the basic sedation concepts with effective communication, crisis management, and advanced life support skills. Each session is followed by a facilitated debriefing session that allows for reflective practice and learning enhancement. The use of videotaping during the simulation sessions provides an objective reference for participants and facilitators during the debriefing. Videotaping encourages a learner-centered approach of self-reflection and transparency, thus maximizing the learning opportunity.

In 2003, the Israeli ministry of health instituted mandatory training for medical providers of pediatric sedation. To meet the growing need for training, the Israeli Center for Medical Simulation (MSR) has developed a simulation-based training program for patient safety during pediatric sedation based on the aforementioned principles (Fig. 35.2). An example of a curriculum for simulation-based basic training in patient safety during pediatric sedation is shown in Table 35.1.

Fig. 35.2

Team training in the pediatric intensive care unit at Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel

Table 35.1

A curriculum of patient safety during pediatric sedation

Learning objectives |

• To acquire proficiency in the use of medication regimens |

• To understand decision making in the context of pediatric sedation medications and patient safety. |

• To become competent in diagnosing and managing adverse sedation reactions |

• To understand and use monitoring technologies including capnometry and capnography |

• To acquire proficiency in essential rescue measures such as airway management, head and recovery positioning, suction, oxygen supplementation, bag-mask ventilation and use of reversal agents, position. |

Course outline: |

• Advanced E-learning theoretical presentation and pretest |

• Introduction |

• Simulation-based skill training for—monitoring technologies, positioning, airway management, and bag-mask ventilation |

• Practice of pediatric sedation simulation-based scenarios: |

– Oversedation leading to airway compromise |

– Sedative overdose leading to apnea and bradycardia |

Minimum requirements for successful completion of the course |

Upon completion of the course, participants are required to pass a written multiple choice examination and a simulated safety-skills session, which includes an evaluation of the participant’s ability to assess and manage airway complications |

In the decade that followed, hundreds of providers, including pediatric residents, fellows, senior physicians, and pediatric nurses were trained using this platform. This type of simulation-based training has significantly improved patient safety and led to better adherence to pediatric sedation protocols by nonanesthesiologists that routinely perform procedural sedation outside the operating room [32]. It demonstrated that following completion of simulation-based training, unsupervised pediatric residents performed procedural sedation in a manner that was safe and comparable to that performed by certified pediatric emergency physicians [33].

Advanced Training

The use of simulation for training and maintaining competencies in pediatric sedation does not end with the completion of the basic initial training. The use of in situ simulation (performing in the clinical setting where procedures take place) is growing rapidly and many units and institutions have developed these capabilities in recent years. In situ simulation enables providers to engage in their own setting, with their own equipment. This can uncover unidentified challenges and variables that could not have been otherwise anticipated [34, 35]. In situ simulation can also serve to monitor and test the efficiency, effectiveness, and applicability of various safety measures and protocols that are used for pediatric sedation [36, 37].

Future Trends

Contemporary medicine is confronted with escalating medical care costs and expanding demands for patient safety. Health care systems must balance the need for safe and high-quality care with the costs of training and assessing the provider competency. As technological developments lead to an ever-expanding diagnostic toolbox and novel potential therapies, there are increasing demands for sedation of children. Pediatric sedation is substantially safer than it was a generation ago. As pediatric sedation becomes safer, the risk of the sedation provider experiencing unintended consequences decreases. Simulation provides an opportunity to experience these increasingly rare events. It is one mechanism by which trainees and providers can be challenged to think beyond their routines and to develop a greater awareness of the complexity and potential hazards of their practice.

Simulation provides flexibility for different levels of experience and adaptability to different clinical domains and social situations. The limitations of simulation are related to financial expense and the limited outcome data. The costs include the purchase and maintenance of the mannequins, the salaries of the simulation staff, and the storage of equipment. A separate simulation center is not required; mobile simulation carts can provide the same experience at a more modest cost [38]. A dedicated simulation center, if remote from areas of clinical service, may actually limit simulation experience by depriving participants of experiencing the actual locations in which sedation is delivered.

Sedation providers for children are required to be certified in basic and advanced life support techniques for children. Current Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) and PALS courses present computer-based simulation scenarios that must be satisfactorily completed prior to application on the mannequin. Students are becoming familiar with this method of training, and have come to anticipate the stresses and challenges of the simulation environment. They are able to repeat the simulation when their performance does not reach their goal and practice until satisfactory performance is achieved.

Pediatric Sedation Simulation Scenario

A pediatric sedation simulation can be created using the most expensive of computer-controlled mannequins or with more modest simulators. Designing and delivering a meaningful simulation experience requires consideration of the purpose of the exercise: Who are the intended participants? What resources are available? What are the curricular goals? The content of simulation scenarios can be adjusted to serve participants of differing experiential levels. For example, a scenario built around a 3-year-old child being sedated for an MRI might be adapted for the early learner to practice MRI safety and basic sedation techniques. It could also be used to introduce more challenging problems such as laryngospasm, anaphylaxis, or pneumothorax. Complicating factors may be built into the scenario to increase their difficulty and make them more appropriate for advanced practitioners. Such content could include communication challenges, medical errors, and delivering bad news to the family. Sedation scenarios are also described in the literature that can be used to guide simulation development. Chen and colleagues described a simulation scenario for airway rescue during pediatric sedation. This was a comprehensive scenario of a 2-year-old child with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia undergoing sedation for PICC line placement and provides a template to follow [39]. The journal Simulation in Healthcare is dedicated to simulation-based investigation and is a resource for obtaining scenarios for program development.

The equipment necessary to run a scenario does not have to be prohibitively expensive and does not require a de dicated onsite simulation suite. It begins with a simulation mannequin. Mannequins are available from numerous vendors with a broad range of prices, sizes, and capabilities. Most can be intubated, can receive chest compressions, and provide cardiac and respiratory sounds. They are usually computer controlled, and some of the most recently developed are controlled by smart pad computers, which have the advantages of ease of use and portability. The vital signs are presented on a computer screen and can be altered by the controller or change in response to the participant’s actions during a scenario. Ultimately, equipment selection is guided by available resources and educational goals. For simulation scenarios, the mannequin does not have to be an expensive high-fidelity computer-controlled machine. Basic pediatric CPR trainers can be used, even without a computer monitor. In such cases, the vital signs and scenario development should be scripted and read to the participant as the scenario unfolds.

Simulation is being increasingly recognized by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) as a method to mark the achievement of milestones by residents and fellows. The methodology of simulation is familiar to medical students who, since 2004, have taken the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 2 Clinical Skills. This exam involves interacting appropriately with simulated patients, taking a medical history, performing a clinical exam, and then writing a summary including a differential diagnosis. Simulation has also been integrated into recertification training for experienced practitioners. The American Board of Anesthesiology’s Maintenance of Certification in Anesthesia (MOCA) program has incorporated simulation as a component of practice performance assessment and improvement for recertification. Participants typically spend a day working on recognition and response to crisis situations, crew resource management, and team training [40].

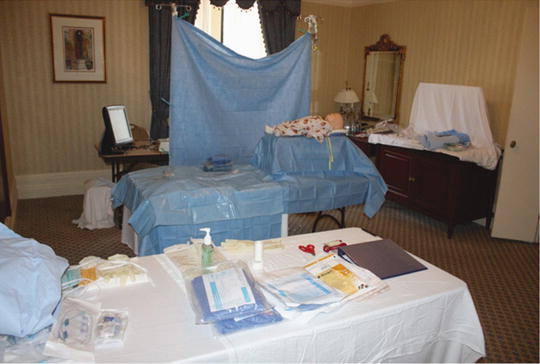

Simulation also can be incorporated more informally as a component workshop at national meetings. The logistics of securing meeting space can be challenging. Such simulations may involve a group of individuals participating in a scenario while the audience observes, or small groups rotating through simulation stations. The latter model has been used at the Pediatric Sedation Outside of the Operating Room conference1 of Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School [41], which is presented in a hotel room (Fig. 35.3). In this model, participants in groups of four to eight rotate for 1 h through a scenario. Five or six scenarios run concurrently and are repeated throughout the day. A range of topics can be covered including crisis resources management, laryngospasm, anaphylaxis, oversedation, airway obstruction, airway foreign body, and the challenging parent. With two to four faculty members participating, there is an extremely favorable student-to-faculty ratio and these sessions are generally positively reviewed.

Fig. 35.3

Setup for onsite simulation in hotel room at the Pediatric Sedation Outside of the Operating Room conference in Boston (www.PediatricSedationConference.com)

In considering how one might use simulation in an educational or evaluative sense, it is helpful to explore a hypothetical scenario. The following pediatric simulation case provides a construct for thinking about how to design, develop, and utilize simulation to train individuals in pediatric sedation. It can be adapted to local situations and modified to prevailing needs. Presented in Table 35.2 is some basic equipment that might be utilized in such a simulation and a proposed scenario template is provided in Table 35.3. The following scenario includes suggestions for equipment to consider making available for the simulation, the simulation script, and a potential checklist of key actions that one might consider should be accomplished by the participant. These key actions are suggested, not validated, and do not represent an absolute gold standard of performance.

Table 35.2

Suggested equipment for pediatric sedation simulations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree