|

MANAGEMENT OF THE NEWBORN BABY

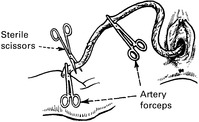

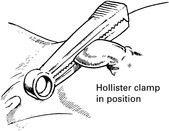

CLAMPING AND LIGATING THE CORD

All mucus, blood and meconium must be sucked out of the pharynx before the baby has a chance to inhale them. This should be done using mechanical suction to minimise the risk of virus transmission.

|

ASSESSMENT OF THE BABY’S CONDITION AT BIRTH

The Apgar scoring system is universally accepted, and evaluation is made at one minute after birth and again at five minutes. A score above 7 indicates good condition. A score of three or less at one minute indicates the need for active full resuscitation which may include external cardiac massage, intubation and ventilation. A score of 6 or less at five minutes suggests perinatal asphyxia but is a poor prognostic indicator. Most infants will establish respiration within three minutes of birth.

| Sign | 0 points | 1 point | 2 points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin colour | Cyanosis pallor | Peripheral cyanosis | Pink |

| Muscle tone | Flaccid | Moves limbs | Good |

| Resp. effort | None | Gasps | Good |

| Heart rate | None | <100 | >100 |

| Response to stimulus | None | Slight | Good |

NEONATAL APNOEA

A relatively high negative pressure is required to overcome lung resistance to expansion, but lung compliance increases thereafter, and progressively less effort is needed. The first breath is all-important, and if it does not occur within one minute of delivery a state of apnoea is considered to exist.

DEGREES OF APNOEA

1. Primary Apnoea

Cyanosed, with some muscle tone and a heart beat over 100. Efforts at breathing are made and gasping occurs.

2. Secondary Apnoea

This is sometimes called terminal apnoea because if not soon corrected brain damage or death will follow. The skin is greyish-white, there is no muscle tone and the heart beat is less than 100. There is associated hypotension which is poorly tolerated by the newborn infant.

It is often difficult in practice to decide on the degree of apnoea, especially when drug-induced depression is present.

CAUSES OF APNOEA

Antenatal

Any condition leading to fetal hypoxia, such as placental insufficiency, pre-eclampsia, placental abruption.

Intrapartum

Prolonged hypoxic labour, traumatic delivery, opiate drugs, anaesthesia. (Even epidural anaesthesia if prolonged.)

Postnatal

Immaturity, cerebral trauma, congenital abnormalities such as diaphragmatic hernia.

MANAGEMENT OF PRIMARY APNOEA

Drugs such as diamorphine, morphine and pethidine, which are commonly used in labour, all cross the placental barrier and cause some degree of respiratory depression and hence asphyxia (an increase in pCO2 and a lowering of the oxygen saturation). Pethidine has been shown to have a more prolonged effect and may retard the development of feeding and other reflexes.

|

SECONDARY APNOEA

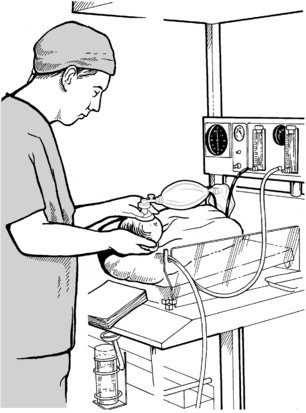

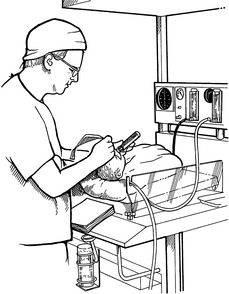

MANAGEMENT OF SECONDARY APNOEA

This technique requires practice and is best done by a paediatrician, but the obstetrician and midwife should have some experience. It is vital to remove any meconium visible in the upper airway and larynx before attempting assisted ventilation.

|

|

Bag and Mask Ventilation

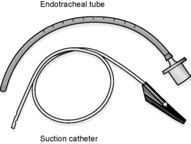

A straight endotracheal tube is usually used but some centres use tubes with a shoulder near the tip to prevent it being inserted too far. The mucus aspirator also shown is small enough to pass through the catheter.

Straight Bladed Laryngoscope

The neonatal larynx lies opposite C3 and 4. The tip of the laryngoscope catches the epiglottis and pulls it forward to allow clear view of the vocal cords.

|

|

|

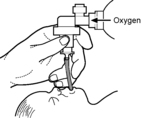

Once the endotracheal tube is inserted, the inflation pressure can be regulated by the bag ventilation. It is usual for the oxygen to pass through a water manometer which ‘blows off’ above a pressure of 30 cm of water.

APNOEA — RESUSCITATION

The first sign or recovery is a quickening and strengthening of the fetal heart, followed by attempts at respiration and improved colour. Once the baby is breathing spontaneously, consideration should be given to transfer to a special nursery.

|

It may be necessary to employ IPPV for up to 20 minutes before respiration becomes spontaneous, or death is recognised as inevitable.

OTHER MEASURES

Cardiac Massage

If the heart rate falls below 80, rhythmic compression should be applied over the sternum, at the rate of about 5 compressions to one inflation of the lungs.

Acidosis

This seldom requires correction once adequate ventilation is established, but in cases of severe asphyxia a combination of plasma volume expansion (normal saline or plasma protein solution) and, very occasionally, judicious infusion of a 0.5 molar solution (4.2%) sodium bicarbonate in 10% dextrose (2ml per kg) may be employed. This may be given via the umbilical vein after insertion of an umbilical catheter.

Hypothermia

An apnoeic baby loses heat very quickly, especially if it is immature and the recommended labour room temperature of 25°C is too low. Local heat must be provided by warm towels and preferably by an overhead radiant heater attached to the resuscitation trolley.

Drugs

Occasionally there may be a place for adrenaline (epinephrine) 1:10000, 1 ml in severe bradycardia or cardiac asystole.

HEAT LOSS IN THE NEWBORN

Heat Production

1. Energy from diet.

2. Metabolic activity mainly in the muscles. (Babies have no protective shivering reflex.)

3. Breakdown of fat. Fat in certain areas such as between the shoulder blades and the perirenal capsule (brown fat) can be catabolised very quickly.

Heat Loss from the Skin

1. Radiation.

2. Evaporation from wet skin exposed to air.

3. Convection.

4. Conduction.

Small amounts of heat are lost through respiration and in urine and faeces.

Clinical Features of Hypothermia (cold injury)

This is rare and avoidable.

The baby is difficult to rouse, cold to touch, lethargic and unwilling to feed. There is oedema of the hands and feet and eyelids and a hardening of the subcutaneous tissues (sclerema). The redness of cheeks and extremities and the absence of crying give a misleading appearance of healthiness. As the metabolism slows down, the baby becomes hypoglycaemic and death occurs.

|

Note oedema of face. Shaded areas represent redness and subcutaneous sclerema.

Treatment

Hypothermia is very difficult to reverse, and the only effective treatment is complete prevention.

1. The labour room temperature should be above 25°C.

2. All resuscitative procedures should be carried out under an infra-red heater.

3. The baby should be dried at birth and covered with a dry towel. It must be well wrapped up if it is staying in the ward.

4. If transfer to a special care baby unit (SCBU) is necessary this must be done in a heated cot. Once in an incubator the paediatrician’s object is to maintain the baby’s temperature at 37°C, and very small babies may require an ambient temperature as high as 37°C.

ROUTINE SCREENING TESTS

CONGENITAL DISLOCATION OF THE HIP (CDH)

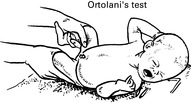

In the normal baby the flexed hip joints should be capable of 90 degree abduction with the baby supine.

|

Limitation of abduction would be an indication for continued investigation and observation.

|

The flexed legs are grasped with the forefingers along the outer aspect of the thigh and the thumb along the inner aspect. If the hip is dislocated, abduction will cause a ‘clunk’ as the femoral head slips into articulation.

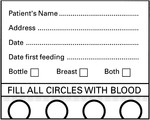

PKU IN THE BABY

Every baby is screened by the Guthrie test which demonstrates abnormal blood levels of PH after feeding is well established (5–10 days).

|

The paper disc impregnated with blood from a heel stab is placed in a bacterial plate of B. subtilis in which there is a special inhibitor. If PH is present in abnormal concentration the inhibitor is neutralised and growth of B. subtilis occurs.

If the test is positive the baby must be subjected to complex tests to establish the type of PKU.

PKU IN THE MOTHER

Transmission is by a recessive gene and it has been estimated that about 1:50000 mothers have undiagnosed PKU. The following ‘at risk’ groups should be screened:

1. Mothers with a family history of PKU.

2. Mothers of low intelligence.

3. Mothers who have had infants with microcephaly (this has an association with PKU).

Screening is complicated by the wide diurnal variation in PH levels and several tests are needed.

A woman with PKU should preferably return to a low PH diet before conception or as soon as she is pregnant. Her infant will also require Guthrie test monitoring.

In the common type 1, the diet must be low-phenylalanine for life. Failure to control PKU results in mental retardation and progressive neurological deterioration.

The Guthrie blood test can also be used to exclude HYPOTHYROIDISM, by measurement of thyroxine levels or thyroid stimulating hormone, the latter being more commonly used.

In the future the blood may also be used to screen for other conditions such as cystic fibrosis.

NURSING CARE

MANAGEMENT OF THE NEWBORN BABY

When given orally to breastfed babies, further doses of oral vitamin K will be required during the first month of life. It is particularly important to give vitamin K after birth if the mother is on oral anticonvulsants.

|

Usually the partner will have been present at birth and the baby is given to the mother and partner to hold as soon as the cord has been cut. If admission to the special care nursery is required, facilities should be provided to allow both parents and other family members to make frequent visits.

Ideally the baby should be offered a period of skin-to-skin contact with the mother, uninterrupted for half an hour. This greatly facilitates breastfeeding.

About 6–8 hours after delivery, traditionally, the baby is bathed and then dressed in a gown and placed in a cot in room temperature between 18 and 20°C.

The ideal cot for the newborn should be draught-proof and easily cleaned. It should be possible to raise and lower the head, and there should be a box for the toilet materials provided separately for each baby.

The importance of ‘bonding’ between the mother and child is widely recognised. Bonding is encouraged by nursing mother and child in the same room, with the cot alongside the bed so that there may be intimate contact. This facilitates demand feeding by the baby.

|

BREASTFEEDING

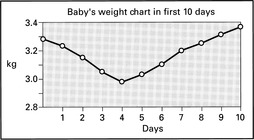

In normal circumstances babies will gain around 30 g per day though there will be initial loss of weight until lactation is established.

|

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE NEWBORN

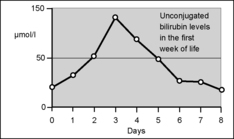

PHYSIOLOGICAL JAUNDICE

The haemoglobin levels fall from 200 g/l at birth to about 110 g/l by the 3rd month. This level rises again over the next 3 months.

|

STOOLS

Meconium (mainly cast-off cells, mucus and bile pigment) is passed for the first 2–3 days. It should appear within 36 hours of birth. The bowel is sterile at birth but is colonised by bacteria within a few hours. Formed stools usually appear by the 5th day, normally light in colour and with the odour of faeces.

RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

The fetal lungs are airless and filled with lung fluid and amniotic fluid. The fetus exists at an arterial oxygen pressure of approximately 4.5–5.5 kPa. This changes quickly to adult levels with the establishment of respiration. The rate is up to 40/minute and there may be much irregularity although this usually settles to under 40 per minute 8 hours after birth.

URINE

The fetus swallows liquor and the kidneys excrete in utero. Urine should be passed within 2 hours of birth.

GENITAL SYSTEM

Manifestations of oestrogen withdrawal may occur. There is sometimes swelling of the breasts and even a little colostrum secretion (‘witches’ milk’). The female may bleed a little from the vagina and the male may develop a transient hydrocele. No treatment is required.

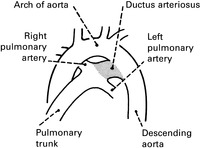

CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

The ductus arteriosus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree