Sinusoidal pattern seen after ruptured membranes associated with anaemia from vasa praevia.

Cord Prolapse

The diagnosis of cord prolapse is made on vaginal examination. The management is to deliver the fetus promptly. Elevation of the presenting part above the pelvic brim will relieve cord compression. This can be achieved by digital displacement, keeping the hand in the vagina until delivery. Alternatively, a knee–elbow position or an exaggerated Sims’ position can be used. Bladder filling with 500 ml of saline using a Foley catheter can also be useful. Tocolysis will help reduce compression of the cord from contractions. If the FHR recovers with these measures then a rapid sequence spinal block can be used in favour of a general anaesthetic.

Abruption

The presence of continued pain between contractions with or without bleeding may suggest an intrapartum abruption as a cause of the fetal distress. This is unlikely to respond to resuscitation.

Uterine Rupture

Fetal distress may be the first sign of impending uterine rupture. The presence of pain between contractions, vaginal bleeding, sudden cessation of contractions or a rise of the presenting part should alert the obstetrician to the possibility of uterine rupture, particularly in a woman at risk. Again, this will not respond to resuscitation.

Fetal distress caused by sudden dramatic labour events will not be reversed with intrauterine resuscitation. However, intrauterine resuscitation is rarely contraindicated, even when immediate delivery is planned, as it will optimize fetal oxygenation during preparation for delivery. Table 6.3 summarizes the potential response to intrauterine resuscitation.

| Yes | Maybe | No |

|---|---|---|

| Hyper-stimulation | Cord compression | Placental abruption |

| Supine hypotension | Placental insufficiency | Uterine rupture |

| Dehydration | Infection | Vasa praevia |

| Hypotension, e.g. following regional anaesthetic | Cord prolapse |

Intrauterine Resuscitation

Maternal Positioning in Left Lateral

An upright or left lateral position reduces the risk of fetal heart decelerations. It makes sense to prevent the effects of aorto-caval compression by discouraging the use of supine or tilt positions in favour of the lateral or upright position. If fetal distress is suspected, then using the lateral position is good practice to correct any revealed or concealed aorto-caval compression.

Stopping the Contractions

Maternal blood flow to the placental villous space is reduced or altered during a contraction. Increasing the frequency of contractions above four in 10 min will reduce gaseous exchange across the placenta.

Recognizing hyper-stimulation is the first step in preventing this. Commonly, this is missed. In the Swedish survey of malpractice claims, 71% had injudicious use of oxytocin, with greater than six contractions observed in 10 min [14]. With hyper-stimulation, the oxytocin infusion must be stopped for a short period of time before recommencing at a lower rate once the fetus has recovered. Oxytocin has a half-life of 15 min; therefore, reducing the rate of the infusion will reduce the serum levels quickly. An infusion should be stopped for at least 15 min before recommencing. Tocolytics should be considered in addition to stopping oxytocin.

Tocolysis

Acute tocolysis or uterine relaxation can be a valuable tool in the management of fetal distress. By correcting the hyper-stimulation causing the fetal distress, it may be possible to continue with the labour or convert an immediate category 1 caesarean to a less-urgent category 2.

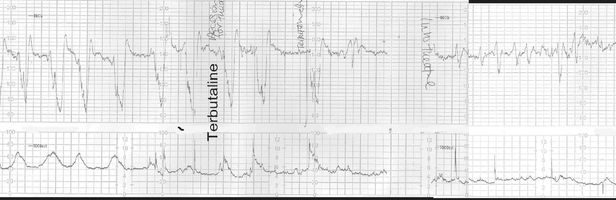

Terbutaline, a betasympathomimetic, is the tocolytic with most published data. The NICE guidance recommends a dose of 250 mcg given subcutaneously [15]. The effect of abolishing contractions can be seen in Figure 6.2. Fears regarding risk of postpartum haemorrhage are largely unfounded in practice. If this does occur, the action can be reversed with 1 mg of propranolol given intravenously.

Cardiotocograph showing the effect of terbutaline on contraction frequency and fetal heart rate.

Atosiban, an oxytocin antagonist developed for the treatment of preterm labour, has the potential for use as an acute tocolytic as it has a favourable side-effect profile and is currently being evaluated. Nitroglycerin as a sublingual preparation (400 mg) has been shown to be useful for acute tocolysis. Its very short duration of action (2–3 min) makes it ideal for use at caesarean section to aid delivery – for example in a transverse lie with no liquor – but not so good for tocolysis in labour, as the dose has to be repeated every 2 min. Side-effects such as hypotension, nausea and headache are common.

Intravenous Fluids

Maternal hypovolaemia and hypotension can decrease the uteroplacental blood supply. For this reason, the NICE guidance recommends assessing the mother for signs of dehydration and/or hypotension when assessing a suspicious CTG in labour, and treatment with a bolus of 500 ml crystalloid is recommended [15]. There are no randomized trials looking at the use of an intravenous fluid bolus for the management of fetal distress, and caution must be used in the presence of pre-eclampsia because of the risk of pulmonary oedema. However, it does seem sensible to correct dehydration and hypotension if present. Intravenous fluid boluses of glucose-containing solutions should be avoided because of potentially detrimental effects on fetal status, including increased fetal lactate and decreased fetal pH.

Amnioinfusion

Amnioinfusion has been used as a treatment for fetal distress with some promising results in trials in resource-poor areas. One potential use is in the case of meconium staining of the liquor to dilute the meconium and therefore make the incidence of meconium aspiration less likely. Unfortunately, trials have not shown the benefit of this [15]. It is likely that the meconium has already been inhaled in utero down to the alveoli levels. Therefore adding more fluid once thick meconium has been seen is unlikely to be of significant benefit.

The other potential use is in the presence of variable decelerations thought to be due to cord compression. The addition of fluid would cushion the cord compression occurring during a contraction. A meta-analysis did show a modest reduction in FHR abnormalities and a reduction in low Apgars and low arterial pH at birth. However, the trials included were too small to address rare but serious maternal side-effects of amnioinfusion [16].

Trials based in centres with standard peripartum surveillance have not demonstrated benefit in either scenario and therefore amnioinfusion is not recommended for management of fetal distress.

Oxygen

Oxygen administration has been shown to increase fetal oxygenation as measured by pulse oximetry, and some studies have shown improvements in FHR patterns. However, oxygen administration may be potentially harmful. Studies have demonstrated that routine oxygenation in the second stage caused deterioration in cord blood gas values. Other studies in animals have shown raised harmful free radicals as a result of maternal oxygen administration, and neonatal resuscitation uses air initially to avoid high concentrations of oxygen, again because of free radical formation.

There is increasing evidence that maternal facial oxygen administration can be a frightening experience for mothers and partners at a particularly stressful time and may distract attention from other preparations for emergency delivery. Based on current evidence, maternal oxygen administration cannot be recommended for intrauterine resuscitation for the fetus [15]. However, pre-oxygenation for the mother is useful if a general anaesthetic is being considered.

Delivering the Fetus

Having considered the fetal reserve, the nature of the insult and the potential or actual response to resuscitation, the decision is whether to expedite delivery.

There is only one randomized trial comparing delivery for fetal distress to a conservative approach which was published in 1959 from South Africa. Women were randomized to intervention (delivery by caesarean, symphysiotomy or forceps), or a conservative approach to fetal distress as picked up by FHR abnormalities on intermittent auscultation or the presence of meconium staining of the liquor. There was a high perinatal mortality rate in both arms of the study, with a significant number of deaths in the intervention group due to trauma. The study was underpowered for differences in perinatal mortality. The Cochrane reviewers concluded that there was too little evidence to show whether operative management is more beneficial than treating factors which may be causing the baby’s distress, and that further contemporary research is needed. Such a trial will be difficult to perform [7].

Caesarean Section or Operative Delivery

Having decided to deliver a distressed baby, the next decision is how to do so. During preparation for delivery, resuscitation methods can continue. In the first stage of labour the option is CS, except in rare circumstances (for example, rapid progress in a multiparous patient or a second twin) where a vaginal birth can be considered.

The classification of urgency is useful in determining good communication with the anaesthetist. The choice of anaesthesia has to be made between the anaesthetist and the mother. Increasingly, regional analgesia is favoured in preference to general anaesthesia. With the use of a ‘rapid sequence’ spinal anaesthetic, a decision interval can be less than the gold standard of 30 min [1]. The use of an urgency classification helps communication between the whole team in preparing for delivery, balancing the need for urgency and adequate careful preparation for the mother.

Poor fetal outcome with instrumental vaginal births relate to inappropriate application and/or excessive traction, particularly at mid-cavity and rotational deliveries in the presence of fetal distress.

A prospective cohort study of 393 women experiencing operative delivery in the second stage of labour reported an increased risk of neonatal trauma and admission to the special care baby unit (SCBU) following excessive pulls (more than three pulls) and sequential use of instruments. The risk was further increased where delivery was completed by CS following a protracted attempt at operative vaginal delivery [17].

The bulk of malpractice litigation results from failure to abandon the procedure at the appropriate time, particularly the failure to eschew prolonged, repeated or excessive traction efforts in the presence of poor progress. The choice of instrument will depend on the skill and expertise of the operator and the assessment of the ease and difficulty of the planned delivery. Mid-cavity and rotational deliveries will have a higher complexity (and thus higher morbidity) than low-cavity and non-rotational deliveries. Opting for CS is not always the safest way for mother or baby, and considerable morbidity can occur to either.

The wise obstetrician in the presence of fetal distress will choose the instrument that will have the best chance of delivering the baby the safest and quickest way with the least risk of failure or use of multiple instruments.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree