Fig. 1.1

Hua Tuo (c. 140–208 ce). The ancient texts Records of the Three Kingdoms and Book of the Later Han record Hua as the first person in China to use anesthesia during surgery, referring specifically to mafeisan. The illustration portrays Hua Tuo’s surgical and medicinal abilities as well as his use of moxibustion

Hindu Drugs

Brahman priests and scholars were the medical leaders in the earliest recorded histories, three of which are of primary importance:

Charaka Samhita (second century CE, but copied from an earlier work)

Susruta (fifth century CE)

Vagbhata (seventh century CE)

The Susruta detailed more than 700 medicinal plants, the most common of which were condiments such as sugar, cinnamon, pepper, and various other spices. Included among them were descriptions of the depressant effects of Hyoscyamus and Cannabis indica. The eponymously named text (Susruta, c. 700–600 bce) described Susruta’s use of wine to the point of inebriation as well as fumitory cannabis in preparation for surgical procedures. Part of the difficulty with so many drugs was that they were not well codified and were prescribed in casual ways by numerous practitioners, who relied on (clinical) observation of effects [6].

Sumerian Drugs

Agriculture developed in the area between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, and a sophisticated cultivation of plant materials useful for the alleviation of symptomatic disease was not only practiced, but also recorded. Nearly 30,000 clay tablets from the era of Ashurbanipal of Assyria (568–626 bce) were discovered in the mid-nineteenth century near the site of Nineveh, capital of the neo-Assyrian Empire, with numerous references to plant remedies. Beers were especially well developed in ancient Babylon. Cannabis indica was known for producing intoxication, ecstasy, and hallucinations, when reinforced with hemp. This was all under the supervision of the priesthood. In addition, hallucinogenic mushrooms were employed in ancient Sumeria. Poppies were used mainly as a condiment in Sumerian life. Although there is no drug activity in the poppy leaves, fruit, or root, if the unripe seed capsule is opened, the white juice resulting from that is (raw) opium, the dried “latex” of which forms alkaloids as it dries. However, opium was not described (as far as we know) in the Ashurbanipal tablets.

Jewish Medicine

Jewish medicine received significant contributions from the Babylonians during the Babylonian captivity (597–538 bce) as well as from the Egyptians during the Egyptian Captivity (a date which is much less clear, based on 430 years of captivity prior to the Exodus, accepted as 1313 bce in rabbinic literature [7]). Jewish potions were prepared by the priesthood for pain relief and the imparting of sleep during surgical procedures, venesection, and leeching; Samme de shinda was probably a hemp potion, but probably not an opium derivative [8].

Egyptian Medicine

The major influence on the emerging Greek world of medicine came from Egypt. Our knowledge of their codification is relatively robust because of the medical papyri, most of which were hieratic (hieroglyphics or ideographs), compiled from around 2000–1200 bce (Table 1.1). They themselves were probably copied from older originals, as evidenced by the use of archaic terminology within the medical papyri, more characteristic of language from around 3,000 bce.

Table 1.1

List of Egyptian medical records

Document | Date | Comment |

|---|---|---|

Kahun Papyrus | 1900 bce | Primarily veterinary medicine |

Edwin Smith Papyrus | 1600 bce | Consists of 48 case histories; a well-organized surgical text |

Ebers Medical Papyrus | 1550 bce | Deals with medical rather than surgical conditions; emphasizes recipes |

Hearst Medical Papyrus | 1550 bce | Poorly organized; a practicing physician’s formulary |

The Erman Document | 1550 bce | Deals largely with childbirth and diseases of children |

The London Papyrus | 1350 bce | Poorly organized; a practicing physician’s formulary |

The Berlin Papyrus | 1350 bce | Poorly organized; a practicing physician’s formulary |

The Chester Beatty Papyrus | 1200 bce | Formulary for anal diseases; one case report |

It is ironic, and somewhat puzzling, that despite the richness of ancient documentation from the aforementioned artifacts, there is a paucity of information about narcotics and sedatives in ancient Egypt. Most of the suggestions about the use of such medications are by inference. For example, Ebers 782 cites “shepnen of shepen” (poppy seeds of poppy) to settle crying children. Interestingly, the poppy seed contains relatively little morphine; it is the latex produced from the incision of the seed pod that actually contains the active ingredient. Another suggestion, by inference, is that base ring juglets were used to import opium from Cyprus in about 1500 bce, because of the resemblance of these juglets, when inverted, to a poppy head [9] (Fig. 1.2) and the reported finding of morphine in an Egyptian juglet from the tomb of Kha (19th Dynasty), although this has been disputed [10]. Cannabis (C. sativa) was prescribed by mouth, rectum, vagina, and delivered transdermally and by fumigation, yet central nervous system effects were not described. The London and Ebers papyri refer to mantraguru, an obvious common origin with mandrake, or Mandragora. Some species of lotus (Nymphaea caerulea and N. lotos) are native to Egypt and contain several narcotic alkaloids that can be extracted in alcohol, leading to a logical hypothesis that lotus-containing wine might have additional narcotic effects. Ebers 209 and 479 both refer to preparations for the relief of right-sided abdominal pain and jaundice (respectively) containing lotus flower as an ingredient, but directing that the lotus flower has to “spend the night” with wine and beer—conditions that would likely permit alkaloid extraction. It is therefore interesting that depictions of the lotus flower being sniffed are the only artifactual suggestion of the possible medical use of lotus (Fig. 1.3).

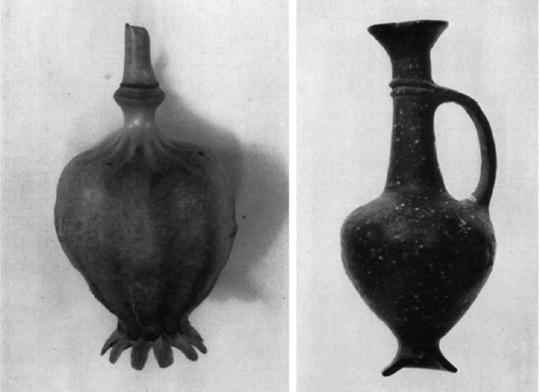

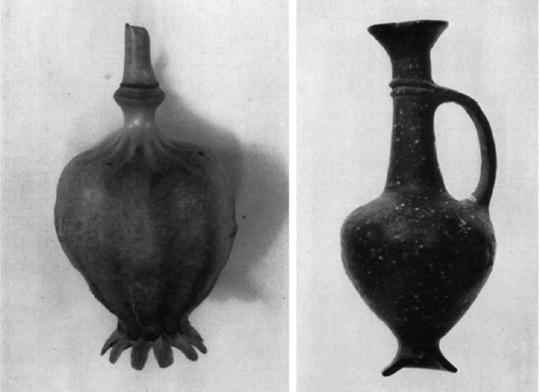

Fig. 1.2

Comparison of an opium poppy capsule and a base ring juglet. An inverted opium poppy capsule on the left, and a base ring juglet from the Bronze Age (dated to Egypt’s 18th Dynasty). Note that the solid pottery base ring takes the place of the serrated upper portion of the capsule, but the flaring angle is almost identical. Overall, the outline of the body of the juglet almost parallels that of the poppy head, and its tall slender neck corresponds to the poppy’s thin stalk

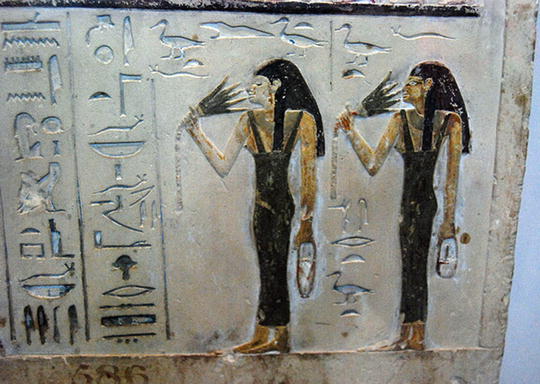

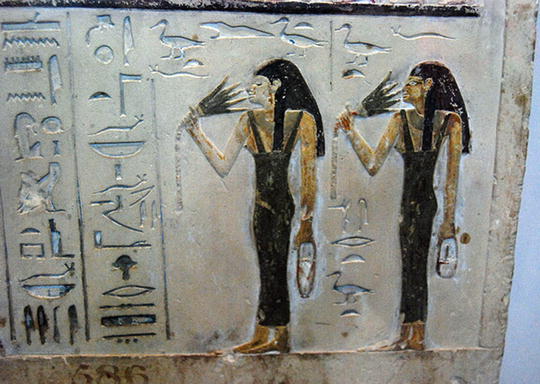

Fig. 1.3

Stela of Ity (from the British Museum EA 586). Painted limestone Stela of Ity, dated to the 12th Dynasty, c. 1942 bce. Ity’s many titles and the names of his mother, wife, sons, and daughters are listed. Note the illustration of the lotus flower being sniffed

All over the world, indigenous people have learned the medicinal properties of plants in their environments and have applied them to medical use. The remarkable acquisition of a sufficient amount of experience to provide the basis for a systematic analysis and an accumulated fund of knowledge, probably transmitted initially through oral tradition and along specific lines of professional authority (physicians, priesthood, specialized castes of drug-gatherers and preparers), undoubtedly took a long time. It is extraordinary, moreover, for its survival and consistency through the ages, laying the groundwork for Classical civilization and beyond.

Classical History

Greek Medicine

Chaldo-Egyptian magic, lore, and medicine were transferred to the coasts of Crete and Greece by migrating Semitic Phoenicians or Jews and the stage was then set for incorporating ancient Egyptian drug lore into Greek medicine. Two prominent medical groups developed on the mainland of Asia Minor: the group on Cnidos, which was the first, and then the group on Kos, of which Hippocrates (460–380 bce) was one member. While they were accomplished surgeons, they generally eschewed drugs, believing that most sick people get well regardless of treatment. Although Hippocrates did not gather his herbal remedies, he did prescribe plant drugs, and a cult of root diggers (rhizotomoi) developed, as did a group of drug merchants (pharmacopuloi). In Greece, plants were used not only for healing but also as a means of inducing death, either through suicide or execution; perhaps the best example was the death of Socrates. Later, Theophrastus (380–287 bc), a pupil of Aristotle (384–322 bce), classified plants and noted their medicinal properties. This was a departure from previous recordings, as Theophrastus analyzed remedies on the basis of their individual characteristics, rather than a codification of combinations as in Egyptian formularies. He provided the earliest reference in Greek literature to mandragora [11].

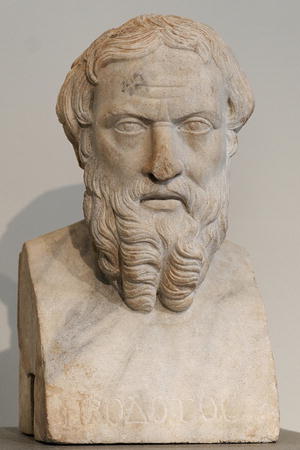

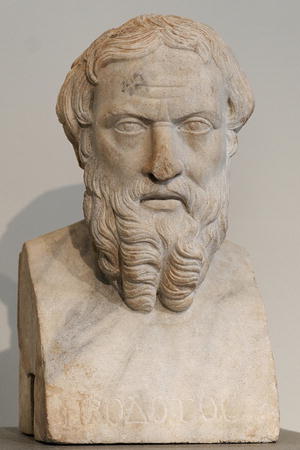

The father of history, Herodotus (484–425 bce) (Fig. 1.4), left a detailed description of the mass inhalation of cannabis in the Scythian baths [12]:

Fig. 1.4

Herodotus (484–425 bce). Source: Marie-Lan Nguyen (2011)/Wikimedia Commons

The Scythians, as I said, take some of this hemp-seed, and, creeping under the felt coverings, throw it upon the red-hot stones; immediately it smokes, and gives out such a vapour as no Grecian vapour-bath can exceed; the Scyths, delighted, shout for joy, and this vapour serves them instead of a water-bath; for they never by any chance wash their bodies with water.

Compression of the great vessels of the neck was also recognized as a form of inducing unconsciousness. It was recognized that compression of the carotid5 arteries would result in unconsciousness and insensibility, as would pressure on the jugular veins. Aristotle recognized this, saying of jugular vein compression, “if these veins are pressed externally, men, though not actually choked, become insensible, shut their eyes, and fall flat on the ground” [13].

The poets Virgil and Ovid described the soporific effects of opium. Virgil (70–19 bce) described the power of the poppy through the personification “Lethaeo perfusa papavera somno” (“poppies steeped in Lethe’s slumber”),6 while Ovid (43 bce–17/18 bce) also invoked the personification of Lethe by stating, “There are drugs which induce deep slumber, and steep the vanquished eyes in Lethean night.”7

Roman Medicine

After the decline of the Greek empire following the death of Alexander the Great (323 bce), Greek medicine was widely disseminated throughout the Roman Empire by Greek physicians, who often were slaves. Dioscorides (c. 40–90 ce) described some 600 plants and non-plant materials including metals. His description of mandragora is famous—the root of which he indicates may be made into a preparation that can be administered by various routes and will cause some degree of sleepiness and relief of pain [14]. Pliny the Elder (23–79 ce) described the anesthetic efficacy of mandragora in the following manner [15]:

…(mandragora is) given for injuries inflicted by serpents and before incisions or punctures are made in the body, in order to insure insensibility to pain. Indeed for this last purpose, for some persons the odor is quite sufficient to induce sleep.

In the first century, Scribonius Largus compiled Compositiones Medicorum and gave the first description of opium in Western medicine, describing the way the juice exudes from the unripe seed capsule and how it is gathered for use after it is dried. It was suggested by the author that it be given in a water emulsion for the purpose of producing sleep and relieving pain [16]. Galen (129–199 ce), another Greek, in De Simplicibus (about 180 ad), described plant, animal, and mineral materials in a systematic and rational manner. His prescriptions suggested medicinal uses for opium and hyoscyamus, among others; his formulations became known as galenicals.

Islamic Medicine

In 640 ce, the Saracens conquered Alexandria, Egypt’s seat of ancient Greek culture, and by 711 ce they were patrons of learning, collecting medical knowledge along the way. Unlike the Christians, who believed that one must suffer as part of the cure, the Saracens tried to ease the discomfort of the sick. They flavored bitter drugs with orange peels and sweets, coated unpleasant pills with sugar, and studied the lore of Hippocrates and Galen. Persian physicians became the major medical teachers after the rise of the Baghdad Caliphate around 749 ce, with some even penetrating as far east as India and China. By 887 there was a medical training center with a hospital in Kairouan in Northern Africa.

The most prominent of the Arab writers on medicine and pharmacy were Rhazes (865–925 ce) and Avicenna (930–1036 ce), whose main work was A Canon on Medicine. The significance of this thread of ancient medical philosophy was that during the eleventh and twelfth centuries this preserved knowledge was transmitted back to Christian Europe during the Crusades. Avicenna noted the special analgesic and soporific properties of opium, henbane, and mandrake [17] (Fig. 1.5).

Fig. 1.5

Avicenna (930–1036 ce). “If it is desirable to get a person unconscious quickly, without his being harmed, add sweet-smelling moss or aloes-wood to the wine. If it is desirable to procure a deeply unconscious state, so as to enable the pain to be borne, which is involved in painful application to a member, place darnel-water into the wine, or administer fumitory opium, hyoscyamus (half dram dose of each); nutmeg, crude aloes-wood (four grains of each). Add this to the wine, and take as much as is necessary for the purpose. Or boil black hyoscyamus in water, with mandragora bark, until it becomes red, and then add this to the wine” [17]

Medieval Medicine

The first Christian early medieval reference to anesthesia is found in the fourth century in the writings of Hilary, the bishop of Poitiers [18]. In his treatise on the Trinity, Hilary distinguished between anesthesia due to disease and “intentional” anesthesia resulting from drugs. While St. Hilary does not describe the drugs that lulled the soul to sleep, at this time (and for the following few centuries) the emphasis remained on mandragora.

From 500 to 1400 ce, the church was the dominant institution in all walks of life, and medicine, like other learned disciplines, survived in Western Europe between the seventh or eighth and eleventh centuries mainly in a clerical environment. However, monks did not copy or read medical books merely as an academic exercise; Cassiodorus (c. 485 ce–c. 585 ce), in his efforts to bring Greek learning to Latin readers and preserve sacred and secular texts, recommended books by Hippocrates, Galen, and Dioscorides while linking the purpose of medical reading with charity care and help.

Conventional Greco-Roman drug tradition, organized and preserved by the Muslims, returned to Europe chiefly through Salerno, an important trade center on the southwest coast of Italy in the mid 900s. One of the more impressive practices documented at Salerno was intentional surgical anesthesia, described in Practica Chirugiae in 1170 by the surgeon Roger Frugardi (Roger of Salerno, 1140–1195), in which he mentions a sponge soaked in “narcotics” and held to the patient’s nose. Hugh of Lucca (ca. 1160–1252) prepared such a sleeping sponge according to a prescription later described by Theodoric of Cervia (ca. 1205–1296). As an added precaution, Theodoric bound his patients prior to incision. The description of the soporific sponge of Theodoric survived through the Renaissance largely because of Guy de Chauliac’s (1300–1367) The Grand Surgery and the clinical practices of Hans von Gersdorff (c. 1519) and Giambattista della Porta (1535–1615), who used essentially the same formula of opium, unripe mulberry, hyoscyamus, hemlock, mandragora, wood-ivy, forest mulberry, seeds of lettuce, and water hemlock (Fig. 1.6).

Fig. 1.6

The Alcohol Sponge [46]. “Take of opium, of the juice of the unripe mulberry, of hyoscyamus, of the juice of hemlock, of the juice of the leaves of mandragora, of the juice of the wood-ivy, of the juice of the forest mulberry, of the seeds of lettuce, of the seeds of the dock, which has large round apples, and of the water hemlock—each an ounce; mix all these in a brazen vessel, and then place in it a new sponge; let the whole boil, as long as the sun lasts on the dog-days, until the sponge consumes it all, and it is boiled away in it. As oft as there shall be need of it, place this sponge in hot water for an hour, and let it be applied to the nostrils of him who is to be operated on, until he has fallen asleep, and so let the surgery be performed. This being finished, in order to awaken him, apply another sponge, dipped in vinegar, frequently to the nose, or throw the juice of the root of fenugreek into the nostrils; shortly he awakes” [47]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree