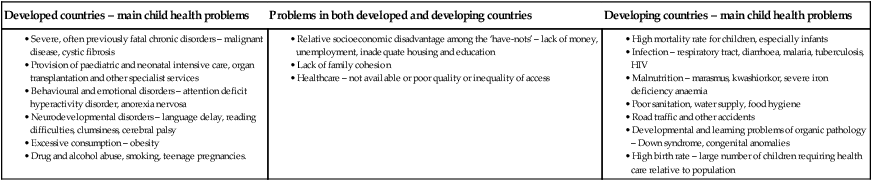

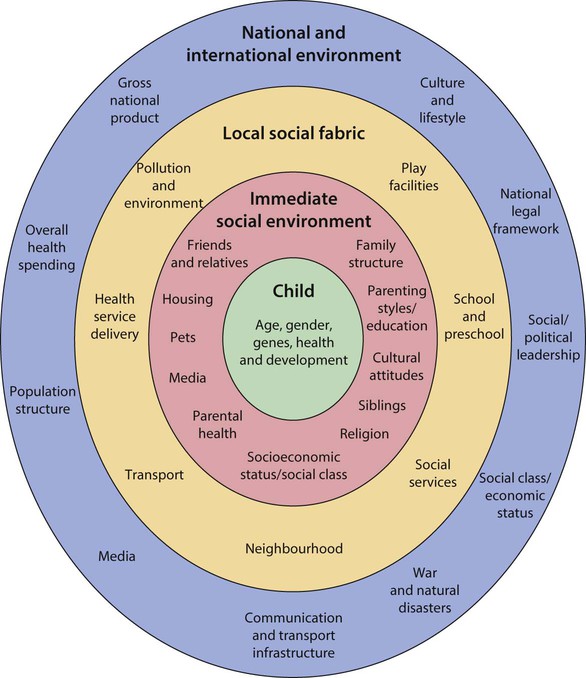

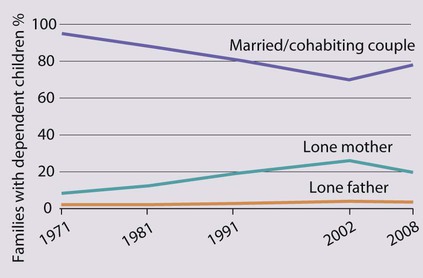

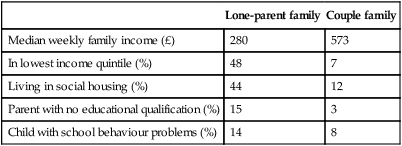

• likely cause: if the diarrhoea is likely to be from a viral illness or from a contaminated water supply if in a developing country • severity of the child’s illness: the organism likely to be responsible and the child’s nutritional status • management options: who will take care of the child when ill; is pre-prepared oral rehydration therapy available; is hospital treatment possible and what facilities can it offer? Important goals for a society are that its children and young people are healthy, safe, enjoy, achieve and make a positive contribution and achieve economic well-being (Every Child Matters, 2003 at: http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/everychildmatters). These are included in the UN Rights of the Child (see below). The way in which the environment impacts on a child achieving good health is exemplified by the contrast between the major child health problems in developed and developing countries. In developed countries these are a range of complex, often previously fatal, chronic disorders and behavioural, emotional or developmental problems. By contrast, in developing countries the predominant problems are infection and malnutrition (Box 1.1). Children’s health is profoundly influenced by their social, cultural and physical environment. This can be considered in terms of the child, the family and immediate social environment, the local social fabric and the national and international environment (Fig. 1.1). Our ability to intervene as clinicians needs to be seen within this context of complex interrelating influences on health. Although the ‘two biological parent family’ remains the norm, there are many variations in family structure. In the UK, the family structure has changed markedly over the last 30 years (Fig. 1.2). Single-parent households – One in four children now live in a single-parent household. Disadvantages of single parenthood include a higher level of unemployment, poor housing and financial hardship (Table 1.1). These social adversities may affect parenting resources, e.g. vigilance about safety, adequacy of nutrition, take-up of preventive services, such as immunisation and regular screening, and ability to cope with an acutely sick child at home. Table 1.1 Comparison between parents who are single or couples General Household Survey, Office for National Statistics, England 2008. Socioeconomic status is a key determinant of health and well-being of children. It is estimated that 2.8 million children in the UK are living in poverty (below 60% of the national median income after adjustment for housing costs). The proportion of children in poverty in different countries is shown in Figure 1.3. Health issues in the UK in which prevalence rates are increased by poverty include:

The child in society

The child’s world

Immediate social environment

Family structure

Lone-parent family

Couple family

Median weekly family income (£)

280

573

In lowest income quintile (%)

48

7

Living in social housing (%)

44

12

Parent with no educational qualification (%)

15

3

Child with school behaviour problems (%)

14

8

Socioeconomic status

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

The child in society