1. Evidence of involvement of 3 organs, systems, and/or tissues

2. Development of manifestations simultaneously or in less than 1 week

3. Laboratory confirmation of the presence of aPL (LAC and/or aCL and/or anti-2GPI antibodies) in titers higher than 40 UI/l

4. Exclude other diagnosis

Definite CAPS:

All 4 criteria

Probable CAPS:

All 4 criteria, except for involvement of only 2 organs, system, and/or tissues

All 4 criteria, except for the absence of laboratory confirmation at least 12 weeks apart associable to the early death of a patient never tested for aPL before onset of CAPS

1, 2, and 4

1, 3, and 4 and the development of a third event in >1 week but <1 month, despite anticoagulation treatment

Table 20.2

Differential diagnosis

CAPS | TTP | HELLP | Sepsis | DIC | HIT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Previous history | Previous APS/SLE/malignancy/pregnancy | Malignancy/non | Pregnancy | Infection | Infection/malignancy | Heparin exposure |

Thrombosis | Large/small vessels | Small vessels | Small vessels | Large/small vessels | Small vessels | Large/small vessels |

Typical antibodies | aPL | Anti-ADAMS-13 | None | None | None | Anti-HP4 |

Schizocytes | Present | Present | Scanty | Scanty | Scanty | Scanty |

Fibrinogen | Normal/high | Normal/high | Normal/high | Normal/low | Normal/low | Normal/high |

20.6 Treatment

Due to its bad prognosis, when CAPS is suspected, an aggressive treatment is justified. However, there are no randomized controlled trials to guide the efficacy of the therapies, and data is based on the reported cases and the analysis of the CAPS Registry [39]. Classically, three aspects have been claimed as the basis to treat this situation. First, the so-called supportive general measures; second, the aggressive treatment of any identifiable trigger; and, finally, the specific treatment [39].

The general measures treatment refers to supportive care. It often includes intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Sometimes, intubation is necessary but, mostly, only ICU admission and tight control are necessary. Whenever possible, classical thrombotic risk factors should be avoided, and external pneumatic compression devices might be used when immobility is a concern. When major surgery aim is not taking out necrotic tissue to control the cytokine storm, surgery procedures should be postponed. Additionally, CAPS patients may benefit from glycemic control, stress ulcer prophylaxis, and blood pressure control [39].

Treatment of any precipitating factor is mandatory. When an infection is suspected, an adequately chosen antibiotic treatment should be started, taking into account the infection site, pharmacokinetics, and organism pharmacodynamics. At the same time, amputation and debridation of necrotic tissue might help in controlling the systemic inflammatory response [39–41].

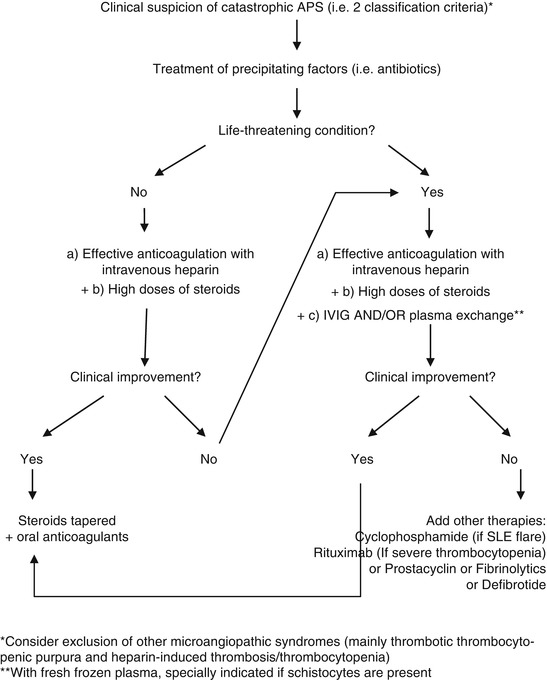

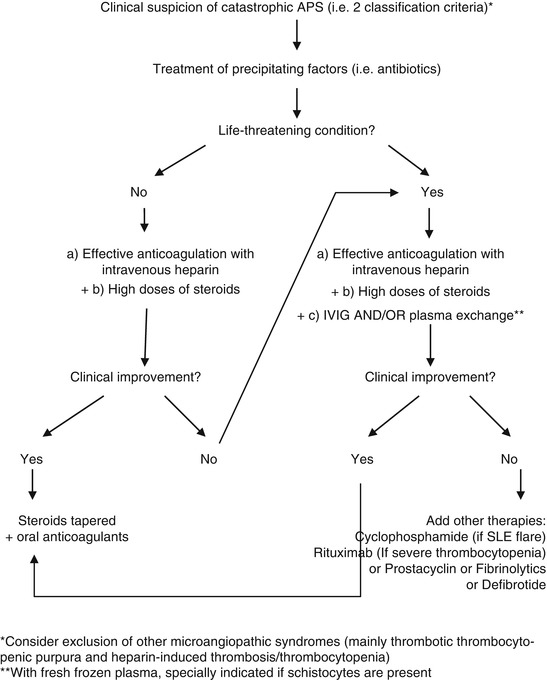

Since no randomized controlled trials have been conducted in CAPS, the specific treatment of this situation is based on the information provided by the analysis of the CAPS Registry and expert opinion. However, these data permitted the establishment of recommendations and the publication of a treatment algorithm [42].

Heparin is the mainstay of treatment in CAPS patients as it inhibits clot formation and lyses existing clots [22, 28, 30, 39, 43, 44]. Non-fractionated intravenous heparin is often chosen when the patient is in the ICU. Heparin does not only inhibit clot generation but also promotes clot fibrinolysis [45]. Additionally, heparin seems to inhibit aPL binding to their target on the cell surface [46]. Moreover, non-fractionated heparin enables throwback of its effect in case of necessity and it has an antidote. Thus, heparin is always the first line of treatment for thrombosis. Later, non-fractionated heparin can be switched to low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and finally to oral anticoagulation. Nevertheless, physician should try to keep patients time long enough with heparin to favor clot fibrinolysis.

The combination of corticosteroids with anticoagulant therapy is the standard of care in CAPS treatment.

Many similarities have been observed between the clinical manifestations of patients with CAPS and systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Since corticosteroids inhibit the nuclear factor (NF)-κB pathway and aPLs seem to signal NF-κB upregulation, beneficial effects of corticosteroids treatment have been invocated. However, in severe infections and in CAPS, no strong evidence has been found supporting corticosteroid use unless patients develop adrenal insufficiency [47, 48]. Until more studies analyzing the use of corticosteroids can be driven, the consensus treatment guidelines [22] should be followed [44], although there is no clear evidence on the route, dose, and duration of this treatment.

Only recently, the beneficial effects of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG) in primary APS have been proved. IVIG proved to decrease aPL titers and therefore, the thrombotic risk of these patients [49, 50]. However, IVIG and plasma exchanges were found few years ago to be a useful complementary tool for the treatment of patients with CAPS [51]. Their high economic cost and low availability may limit their use in patients with CAPS [52]. In this sense, an algorithm for the treatment of CAPS was published in order to guide physician facing these patients and establish treatment priorities [53]. This algorithm proposed to start specific treatment by handling independently each one of the main pathologic pathways. The authors recommended starting on anticoagulation and steroids as soon as the catastrophic situation is suspected. The former is given in order to stop the thrombophilic state and promote clot lysis and the later to downregulate the cytokine storm thought to be the one responsible for SIRS. When the patient is thought to be in a life-threatening condition, the authors suggested adding treatment with IVIG and/or plasma exchanges [53]. In case of active lupus manifestations, treatment with cyclophosphamide should be considered due to the better prognosis of these when they are treated with this drug. Cyclophosphamide is a nitrogen mustard-alkylating agent that binds to deoxyribonucleic acid in immune cells leading to cell death. Cyclophosphamide, probably, promotes the proliferation of T cells, suppression of helper Th1 activity, and enhances Th2 response (Fig. 20.1) [54].

Fig. 20.1

Treatment algorithm of catastrophic APS. Abbreviations: IVIG intravenous immunoglobulins, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus

Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody against CD20, a surface protein expressed on the cytoplasmic membrane of B cells. Rituximab is approved for the treatment of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and rheumatoid arthritis [55]. However, it has been used extensively for the treatment of several other autoimmune diseases [56–58]. Although two randomized controlled trials failed to demonstrate its effectiveness in SLE, it seems to be safe for the treatment of APS. Rituximab has been proposed as a second-line therapy when facing refractory CAPS cases with a relapsing course [59]. The analysis of 18 cases from the CAPS Registry showed that 80 % of them recovered from the CAPS episode in front of the 20 % who did not [22, 59]. Nevertheless, the small number of patients treated with rituximab makes difficult to propose definitive conclusions, but in light of these good results, rituximab has been also proposed as first-line therapy.

20.7 Prognostic

Despite aggressive treatment, mortality in patients with CAPS continues to be high [48]. It accounts for almost 30 % of cases according to the CAPS Registry data [3, 48, 60]. This disease normally have monophasic course, and most patients surviving a CAPS remain symptom free with anticoagulation, although some develop further APS-related events [61]. However, although rare, cases with a recurrent course have been reported. Of note, they present high prevalence of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia laboratory features [51, 62].

References

2.

3.

Cervera R, Rodríguez-Pintó I, Espinosa G (2014) On behalf of the Task Force on Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: task force report summary. Lupus 23:1283–1285

5.

6.

7.

Meroni PL, Raschi E, Camera M, Testoni C, Nicoletti F, Tincani A et al (2000) Endothelial activation by aPL: a potential pathogenetic mechanism for the clinical manifestations of the syndrome. J Autoimmun 15:237–240PubMedCrossRef

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree