Chapter 53 Teaching Visual

Growth Plate Fracture Classification

Medical Knowledge

The pediatric skeleton has unique features that allow for growth and contribute to patterns of injury different from those of an adult. The periosteum of a child is thicker and stronger and has greater osteogenic potential, leading to more rapid callus formation in the setting of fracture. The cortex of pediatric bone is more porous, making it more flexible and able to withstand a greater degree of deformation.1 In addition, remodeling (correction of fractured bone alignment) is generally more predictable. For these reasons, children are generally less likely than their adult counterparts to require surgical management of uncomplicated fractures.2 However, they are also susceptible to unique complications, including growth arrest.3

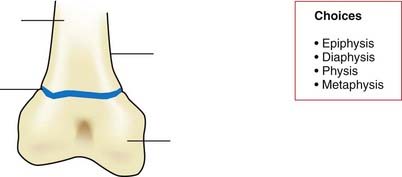

The physis is composed of radiolucent cartilage that is weaker than bone and therefore more susceptible to fracture.1,2 Although uncommon, growth disturbance can occur as a complication of physeal fracture and is related to a number of factors, including the location within the affected physis. Classification of physeal fractures is paramount to guiding management, assessing risk, and predicting prognosis.1 In Figure 53-1, label the parts of the immature long bone as described in the text.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree