(1)

Department Obstetrics & Gynaecology, St George Hospital, Kogarah, New South Wales, Australia

Abstract

This chapter deals first with incontinence/voiding dysfunction, then prolapse and fecal incontinence. Detailed history taking for bacterial cystitis and interstitial cystitis is included in the relevant chapters, but the basic features are given here.

This chapter deals first with incontinence/voiding dysfunction, then prolapse and fecal incontinence. Detailed history taking for bacterial cystitis and interstitial cystitis is included in the relevant chapters, but the basic features are given here.

Many urogynecology patients have multiple symptoms, for example, mixed stress and urge leak along with prolapse or postoperative voiding difficulty with recurrent cystitis and dyspareunia. It is important to untangle or dissect the different problems and then tackle them one by one (although the total picture must fit together at the end).

To help you manage the patient, ask, “What is your main problem. What bothers you the most?” Only after you have sorted this question out fully should a systematic review be undertaken. Let the patient tell you her story.

History Taking for Incontinent Women

Incontinence Symptoms

Stress Incontinence (leakage with cough, sneeze, lifting heavy objects; see Fig. 1.1a). Note that stress incontinence is a symptom. Stress incontinence is a physical sign (see Chap. 2). Urodynamic stress incontinence means that on urodynamic testing the patient leaks with a rise in intra-abdominal pressure, in the absence of a detrusor contraction (see Fig. 1.1b and Chap. 4).

Figure 1.1

(a) Stress incontinence, leakage associated with raised intra-abdominal pressure. (b) Urge incontinence, leakage associated with a detrusor contraction

Urge incontinence (leakage with the desperate desire to void) is a symptom that is difficult to elicit on physical examination (see Chap. 2).

On urodynamic testing, if the patient leaks when a detrusor contraction occurs, associated with the symptom of urgency, the condition is termed detrusor overactivity (see Chap. 4).

Many patients will have mixed stress and urge incontinence but can tell you which one bothers them the most or makes them leak the most.

Take the time to ask the patient, because this guides initial therapy and helps you to interpret urodynamic tests.

Nonincontinent Symptoms of Storage Disorders: Frequency, Urgency, and Nocturia

Frequency of micturition is defined as eight or more voids per day.

The normal adult with an average fluid intake of 1.5–2 l/day will void five to six times per day.

If a woman has increased frequency, ask whether she voids “just in case”: before going shopping and so on, because many women with stress incontinence do this to avoid having a full bladder when they lift shopping bags and the like. The difference is important.

The woman with an overactive detrusor muscle will rush to the toilet frequently because she has an urgent desire to void, caused by the bladder spasm, and she is afraid she will leak if she does not make the toilet on time. The urgent desire to void for fear of leakage is defined as “urgency.”

Nocturia is defined as the regular need to pass urine once or more per night in women aged 60 or less. One episode of nocturia is allowed per decade thereafter, for example, twice per night in the 70-year-old is not considered abnormal (as renal perfusion in the elderly improves at night when the patient lies down and blood flow to the kidneys increases).

The overactive bladder (OAB) is a clinical syndrome, not a urodynamic diagnosis. It comprises frequency, urgency, and nocturia, with or without urge incontinence (in the absence of bacterial cystitis or hematuria). It was defined by the International Continence Society in order to help general practitioners to identify patients likely to have detrusor overactivity, so that they could be treated in the general practice setting without recourse to urodynamic testing.

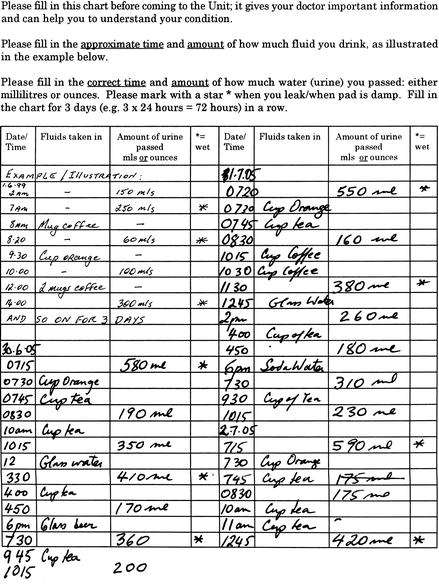

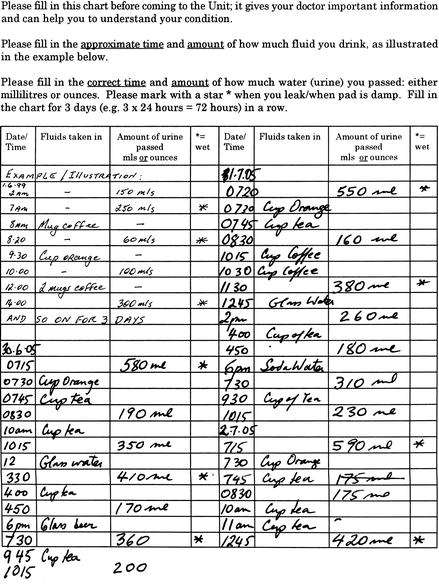

The Frequency–Volume Chart (FVC)

This chart (Fig. 1.2) is especially helpful in assessing whether the patient suffers from daytime frequency or nocturia and how much urine she generally can store (her functional bladder capacity). The average patient has difficulty remembering exactly how often she voids and of course has no idea of the volume she can store.

Figure 1.2

Frequency–volume chart, showing a patient with good bladder volumes, adequate fluid intake, and typical stress leak. Note the “just in case” voiding before going to work (08:30) and coming home (4:50 P.M.) on the train

Most urogynecologists send out a blank FVC to patients prior to the first visit, so she can complete it before the first visit. See Chap. 5 (Outcome Measures) for more detail. This is a crucial part of starting bladder training for patients with overactive bladder (see Chap. 7).

Other Types of Leakage

These may denote a more complex situation.

Leakage when rising from the sitting position can be due to stress incontinence (relative rise in abdominal pressure when standing) or due to urge incontinence (gravitational receptors in the wall of the bladder trigger a detrusor contraction upon standing).

“Leakage without warning” is a nonspecific but important symptom. It may indicate detrusor overactivity, when a patient reaches her threshold bladder volume triggering a detrusor contraction. It may also indicate stress incontinence that the patient cannot verbalize; for example, she leaks with the slightest movement.

Leakage when arising from bed at night to go to the toilet is also nonspecific but important. Nocturia usually is associated with an overactive bladder. However, some patients with a very weak sphincter and other causes for nocturia (such as night sweats, obstructive sleep apnea, or a snoring husband) may leak as soon as they get up to go to the toilet. Leakage during intercourse is seldom volunteered. Ask this question tactfully. Coital incontinence that occurs during penetration is most likely due to stress incontinence, whereas leakage during orgasm is more likely due to detrusor overactivity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree