The obstetric population is generally fit and healthy with a small proportion of women in this age group having pre-existing disease. When there is pre-existing disease the ideal approach would be for the patient to be assessed before pregnancy as described for pre-pregnancy care. Either at this stage, or when pregnancy has occurred, the approach of the obstetrician must be to involve a multidisciplinary team of colleagues. Thus management of conditions such as diabetes, epilepsy or heart disease must involve the expertise of the appropriate physicians.

CARDIAC DISEASE

EFFECTS OF PREGNANCY ON HEART DISEASE

EFFECT OF HEART DISEASE ON PREGNANCY

PRE-PREGNANCY AND EARLY PREGNANCY ASSESSMENT

TERMINATION AND SURGICAL TREATMENT

ANTENATAL CARE

HEART DISEASE — LABOUR AND DELIVERY

1. Position

2. Analgesia

3. Antibiotics

5. Third Stage

ACUTE PULMONARY OEDEMA

PUERPERIUM

PERIPARTUM CARDIOMYOPATHY

RESPIRATORY DISEASES

ASTHMA

CYSTIC FIBROSIS

VENOUS THROMBO-EMBOLISM

Changes in Rate of Flow

Changes in Vascular Intima

DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS

1. Clinical Features

3. Diagnosis

a). Venography

b). Duplex ultrasound

4. Treatment

5. Prophylaxis

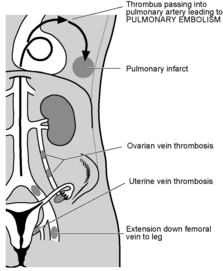

PULMONARY EMBOLISM

Diagnosis

Treatment

Systemic Diseases in Pregnancy

In considering systemic diseases in pregnancy consideration must be given to two basic issues:

1. The effect of the pregnancy on the disease.

2. The effect of the disease (and its treatment) on the pregnancy.

Between 1997 and 1999 there was a total of 35 deaths as a result of heart disease in pregnancy in the UK. Because of the reduction in the numbers of deaths from other causes, heart disease now equals thrombo-embolism as one of the leading reported causes of maternal death. Of these deaths, 10 resulted from congenital causes and 25 from acquired disease.

One third of the causes of congenital heart disease contributing to death comprised women with primary pulmonary hypertension. Some of these cases are hereditary and at least one gene responsible for some cases has been identified.

Of the 25 cases of acquired cardiac disease the majority, seven, resulted from puerperal cardiomyopathy. This represents a significant change over the years in the underlying pathology of cardiac disease in pregnancy and its contribution to maternal death.

Further, older motherhood and lifestyle habits have led to an increasing number of cases of ischaemic heart disease.

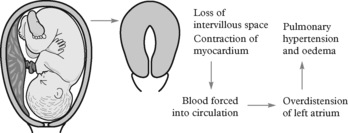

The physiological changes in the cardiovascular system have been described in Chapter 2. In summary it can be said that there is an early and sharp rise in cardiac output in the first trimester and a further slower rise to a maximum of 40% above normal in mid-pregnancy. During labour, cardiac output rises even higher during contractions but falls again between contractions. There is a significant rise after delivery when dramatic changes take place in the uterine blood flow due to reduction in flow to the placental bed. This acts almost like a sudden autologous blood transfusion and, in cases of heart disease, may result in considerable myocardial compromise.

The effect of pregnancy on heart disease, in general then, is to increase the risk of cardiovascular compromise, most noticeably in labour and the third stage in particular. Cardiac failure may occur gradually, however, throughout pregnancy as the heart fails to meet the demands on the circulation.

Left heart failure, presenting as pulmonary oedema, may present early in pregnancy in those with moderate or severe disease. More commonly acute failure is precipitated when situations such as marked tachycardia of 110 per minute reduce the interval for ventricular filling with resulting pulmonary vascular congestion.

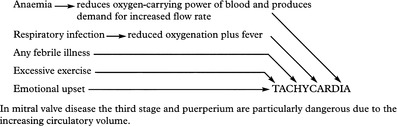

Common aggravating factors are:

Infective endocarditis is a significant risk indicating the need for antibiotic prophylaxis during labour. Other infections during pregnancy may cause endocarditis and women with cardiac disease who are febrile should be treated with appropriate antibiotics and carefully observed.

a) Pre-pregnancy counselling is important for women with known heart disease. It allows a detailed assessment of their cardiac status and the likely effect of pregnancy on it. Women with certain conditions such as Eisenmenger’s syndrome should be told that pregnancy is absolutely contraindicated.

b) A heart murmur may be detected for the first time at the booking antenatal visit. Haemic systolic murmurs are common in pregnancy and the significance of such a finding can be difficult to determine. Careful enquiry should be made for any history which might suggest organic heart disease. Assessment by a cardiologist should be requested.

c) Patients with known heart lesions should be supervised throughout the pregnancy jointly by obstetrician and cardiologist.

Termination of pregnancy is not usually indicated on grounds of cardiac disease alone. Exceptions to this are lesions such as Eisenmenger’s syndrome (mortality 30–50%). Fallot’s tetralogy also carries a small but appreciable mortality (1%) in corrected cases.

After 12 weeks gestation the risks of termination are as great as continuing the pregnancy.

The decline in the incidence of rheumatic heart disease means that mitral valve disease, and consequently valvotomy, are very rare. Minor lesions such as uncomplicated septal defects and patent ductus arteriosus rarely justify surgical treatment during pregnancy.

This is shared between the obstetrician and the cardiologist. The principles are simple: plenty of rest and avoidance of the aggravating factors mentioned earlier.

1. The majority of cardiac patients may be managed as outpatients or attend a day care assessment unit. Admission for rest and treatment must be available at any time. Any deterioration in the cardiac state is an indication for admission and expert cardiological opinion.

2. Any infections should be treated vigorously. Smoking should be strongly discouraged and any chest infection managed by admission, antibiotic treatment and physiotherapy.

3. Anaemia should be avoided and, when found, treated appropriately.

4. Good dental care is essential. All dental surgery should be covered with antibiotics to avoid the risk of bacterial endocarditis.

5. Patients with prosthetic cardiac valves or in atrial fibrillation may be receiving anticoagulants. Warfarin is the most appropriate anticoagulant but carries the risk of fetal damage. Conversion to intravenous heparin may be considered for the first trimester although fetal effects of warfarin are not restricted to the first trimester.

The aim should be to make the labour as easy and non-stressful as possible. Prolonged labour is physically and emotionally draining and increases the risk of infection.

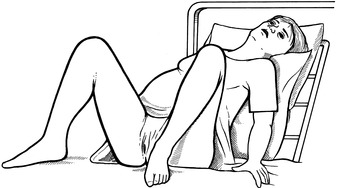

The patient should labour in a propped-up, comfortable position. She may maintain this position for delivery, even when this has to be assisted. The lithotomy position should be avoided because of the sudden increase in venous return to the right side of the heart when the legs are raised above the level of the atria.

Good analgesia is essential in order to avoid the tachycardia associated with labour pain.

Epidural anaesthesia is the method of choice provided hypotension is avoided. This also facilitates operative delivery should this become necessary. Morphine or diamorphine given intramuscularly have much to commend them if an epidural service is not available.

It is now standard practice to give antibiotic prophylaxis to protect against the dangers of bacterial endocarditis in women with structural cardiac lesions. Intramuscular administration of ampicillin and gentamicin is recommended.

There should be no hurry at this point. Time should be allowed for circulatory adjustment as blood returns from the uterine circulation as the uterus contracts. The risks of atonic postpartum haemorrhage must be balanced against the risk of tachycardia and hypotension associated with the use of oxytocin.

In women with severe heart disease a maximum of 5 units of oxytocin should be given over some minutes. In the UK women with such severe disease delivery will often be by caesarean section with a multidisciplinary team in attendance. Delivery by section permits direct uterine compression following delivery if an atonic situation persists following circulatory redistribution of blood.

The patient quickly becomes dyspnoeic and may have frothy sputum or haemoptysis. She should be propped up and, if possible, the legs allowed to hang over the edge of the bed. Oxygen should be given by face mask.

Morphine (5–15 mg) may be given intra-muscularly and furosemide (20–40 mg) given intravenously. Venous return can be reduced by applying inflatable cuffs to the limbs. These measures will reduce the need for more invasive techniques. A cardiology opinion should be obtained about further management.

Early ambulation with appropriate rest is advised. Vigilance should be maintained for signs of infection. Pyrexia merits blood cultures.

Counselling about the risks of future pregnancies should be provided.

This condition occurs in the last month of pregnancy or first five months after delivery. The cause is unknown but may be autoimmune or postviral in origin. Its management is largely of cardiac failure and anticoagulants may be required to prevent thrombi forming in the dilated cardiac chambers.

The patient’s usual medication can be maintained. Inhaled sympathomimetics such as salbutamol remain the mainstay of treatment. Inhaled steroids may be continued if required.

Systemic steroids should be given without hesitation if indicated for acute severe asthma since the dangers of hypoxia to mother and fetus greatly outweigh any disadvantage.

Young women with cystic fibrosis (CF) are increasingly entering the reproductive age group due to advances in treatment. Mild or moderate CF is not a contraindication to pregnancy but ideally these women should be seen preconceptionally and respiratory function optimised.

In the presence of pulmonary hypertension, risks are increased both for the woman and her fetus.

Treatment is multidisciplinary, with attention to adequate nutrition, appropriate antibiotic use and, when required, vigorous physiotherapy.

The pathologist Virchow described a triad of causes of venous thrombosis:

1. Changes in the composition of blood.

2. Changes in the rate of blood flow.

3. Lesions of the vascular intima.

In general, changes in the composition of the blood play a minor role in venous thrombosis in pregnancy except in situations such as dehydration, as in hyperemesis gravidarum, and in pre-eclampsia, in which the intravascular fluid volume is reduced.

Increasingly the hereditary thrombophilias, such as protein S and protein C deficiency and Anti-thrombin III deficiency are being recognised as contributors to antenatal venous thrombosis.

The rate of flow in the leg veins is much reduced in the later weeks of pregnancy, partly from pressure on the pelvic veins by the gravid uterus, and also from the reduced activity of the woman advanced in pregnancy. Bedrest in pregnancy for any reason will increase this risk. Early mobilisation after delivery is now invariable.

These can result from hypertensive disease, surgery and local or blood-borne infection which can follow any delivery, spontaneous or operative. The risk of thrombo-embolism after caesarean section is 5 times higher than after vaginal delivery.

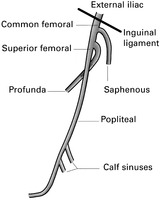

Sites of thrombus formation:

1. Calf veins (often extending to the popliteal vein).

2. Common femoral vein.

3. Iliofemoral (perhaps extending to the vena cava).

4. Saphenous vein at or above the knee.

5. Superficial thrombosis in varices.

Emboli may come from any of these sites except the last. Unfortunately, in many cases of pulmonary embolism there are no preceding signs of venous thrombosis. Diagnosis of venous thrombosis is difficult and many cases suspected on clinical examination prove normal on investigation.

There may be no complaint, but examination of the legs either as a routine or in search of the cause of a mild pyrexia may reveal signs.

This is not always easy as the clinical signs are unreliable. Because of the dangers of the condition, the risks of treatment and the implications for the future it is important to establish the diagnosis accurately.

Venography is the most established technique for diagnosis. Unfortunately it relies on the use of X-rays following the injection of a radio-opaque dye. When used in pregnancy the fetus must be shielded from irradiation.

Compression ultrasonography of the deep veins. Repeat testing may be required to identify thrombi extending into the proximal deep veins since it is these which are thought to be clinically significant. The test is easily repeatable and non-invasive.

As warfarin crosses the placenta, heparin is preferred as it carries no risk to the fetus. If warfarin is used it should be replaced with heparin for the last three weeks of pregnancy to reduce the risk of fetal intra-cranial haemorrhage.

Osteoporosis and thrombocytopenia are complications of prolonged heparin therapy and careful monitoring of heparin levels is required. The former is not common with low molecular weight heparins but platelet levels must be checked regularly in all women receiving heparin.

Anticoagulation can be discontinued during labour and, after delivery, warfarin can be commenced for a period of at least 6 weeks.

Preventing stasis. Patients with varicose veins should wear full-length elasticated stockings. Bedrest should be discouraged both before and after delivery. All puerperal patients should be seen by the physiotherapist. A short postnatal stay, if mother and baby are well, should be encouraged.

In the non-acute situation a ventilation/perfusion scan may be helpful. In severe cases in which surgery may be required, pulmonary angiography is indicated. The role of spiral computed tomography in the evaluation of pulmonary embolism is still being evaluated. These cases should be managed with the aid of physicians with an interest in chest disease.

Continuous intravenous heparin, as described earlier, is employed. Admission to an intensive care unit may be advised.