CHAPTER 12 Surgical Treatment of Chest Wall Deformities

Open Repair

Step 1: Surgical Anatomy

♦ The severity and configuration of the pectus excavatum deformity vary widely. The depression involves posterior displacement of the sternum as well as the costal cartilages. The depression may also be linked with a protrusion of one side creating a “mixed” deformity.

♦ In teenagers, the posterior curvature of the ribs often involves part of the bony ribs as well as the cartilaginous portion.

♦ Another key consideration for these patients is the degree of asymmetry of the excavatum configuration. In some patients there is a marked asymmetry, often with a much shorter anteroposterior (AP) diameter of the chest on the right than on the left side. The sternum in these patients is often rotated with the right side down, and the ribs may actually take off at almost a right angle from the sternum. Surgical repair should address all of these anatomic components.

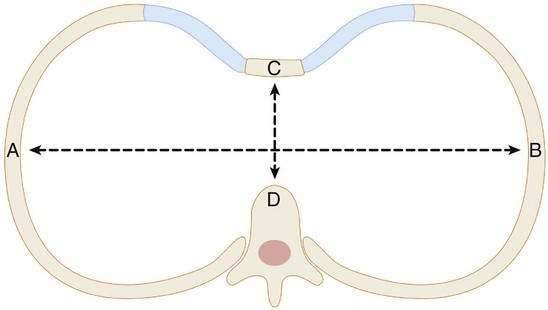

♦ The severity of the depression is often assessed using the Haller index, in which the transverse diameter of the chest (Fig. 12-1 A–B) is divided by the shortest distance between the sternum and the spine (Fig. 12-1 C–D). Indices greater than 3.25 are generally considered significant and appropriate for repair.

Step 2: Preoperative Considerations

♦ Many studies of the cardiopulmonary effects of the pectus excavatum have been completed in the last two decades. A “restrictive” pulmonary defect is often present in patients with an excavatum configuration.

Step 3: Operative Steps

Positioning

♦ The patients’ arms are best placed at their side to maintain symmetry and to allow the surgeon access to the entire side of the patient during the surgical repair.

Incision

♦ In females, the incision is placed in the inframammary crease. I mark this with the patient sitting in the preoperative area to ensure that it is correctly identified. The incision must not extend onto the breast, which can produce “tethering” of the scar between the breasts.

♦ Skin flaps are then developed superiorly to the level of the highest cartilage to be resected and inferiorly to allow exposure of the triangular insertion of the rectus muscle onto the base of the sternum.

♦ The pectoral muscles are mobilized off the sternum beginning at their insertion on the sternum, and care is taken to avoid injury of the periosteum, which in teenagers can result in significant bleeding (see Fig. 12-2). The muscle flaps are elevated to the lateral extent of the deformity. Ellis (1997) has described performing this flap elevation mobilizing the pectoral muscles with the skin flap rather than as separate layers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree