CHAPTER 1 Surgical anatomy

Introduction

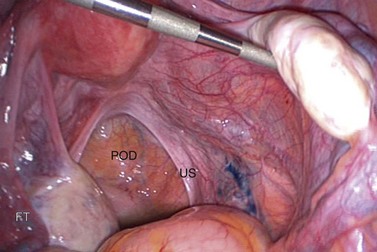

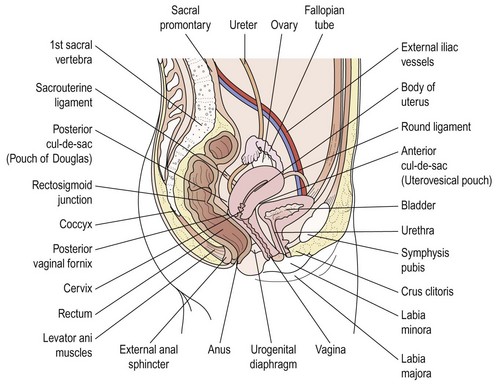

A clear understanding of the anatomy of the female pelvis is essential to successful gynaecological surgery and the avoidance of surgical morbidity. The close relationships between the reproductive, urinary and gastrointestinal tracts must be appreciated, together with the pelvic musculofascial support, vascular and lymphatic circulations, and neurological innervation. It is important to understand the effect of pneumoperitoneum on the anatomy and relationships of the pelvis, and the opportunities afforded by a retroperitoneal approach in minimal access techniques. Figure 1.1 shows a panoramic view of the pelvis from the umbilicus during a laparoscopy. The probe is lifting the right ovary, displaying the right pelvic side wall and ureter (arrows).

The Ovary

Structure

The ovary has a central vascular medulla, consisting of loose connective tissue containing many elastin fibres and non-striated muscle cells, and an outer thicker cortex, denser than the medulla and consisting of networks of reticular fibres and fusiform cells, although there is no clear-cut demarcation between the two. The surface of the ovary is covered by a single layer of cuboidal cells, the germinal epithelium. Beneath this is an ill-defined layer of condensed connective tissue, the tunica albuginea, which increases in density with age. At birth, numerous primordial follicles are found, mainly in the cortex but some in the medulla. With puberty, some form each month into Graafian follicles which, at later stages of their development, form corpora lutea and ultimately atretic follicles, the corpora albicantes (Figure 1.2).

Blood supply

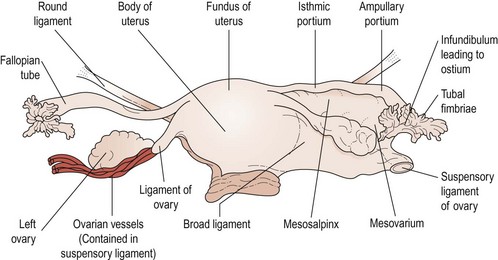

The main vascular supply to the ovaries is the ovarian artery, which arises from the anterolateral aspect of the aorta just below the origin of the renal arteries. The right artery crosses the anterior surface of the vena cava, the lower part of the abdominal ureter and then, lateral to the ureter, enters the pelvis via the infundibulopelvic ligament. The left artery crosses the ureter almost immediately after its origin and then travels lateral to it, crossing the bifurcation of the common iliac artery at the pelvic brim to enter the infundibulopelvic ligament. Both arteries then divide to send branches to the ovaries through the mesovarium. Small branches pass to the ureter and the fallopian tube, and one branch passes to the cornu of the uterus where it freely anastomoses with branches of the uterine artery to produce a continuous arterial arch (see Figure 1.3).

The Uterus

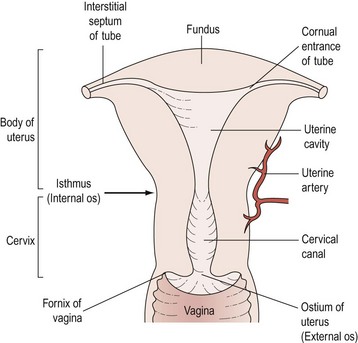

The uterus is shaped like an inverted pear, tapering inferiorly to the cervix and, in the non-pregnant state, is situated entirely within the lesser pelvis. It is hollow and has thick muscular walls. Its maximal external dimensions are approximately 9 cm long, 6 cm wide and 4 cm thick. The upper expanded part of the uterus is termed the ‘body’ or ‘corpus’. The area of insertion of each fallopian tube is termed the ‘cornu’ and that part of the body above the cornu, the ‘fundus’. The uterus tapers to a small central constricted area, the isthmus, and below this is the cervix, which projects obliquely into the vagina and can be divided into vaginal and supravaginal portions (Figure 1.4).

The cavity of the uterus has the shape of an inverted triangle when sectioned coronally; the fallopian tubes open at the upper lateral angles (Figure 1.5). The lumen is apposed anteroposteriorly. The constriction at the isthmus where the corpus joins the cervix is the anatomical internal os.

Figure 1.5 Sectional diagram showing the interior divisions of the uterus and its continuity with the vagina.

The Vagina

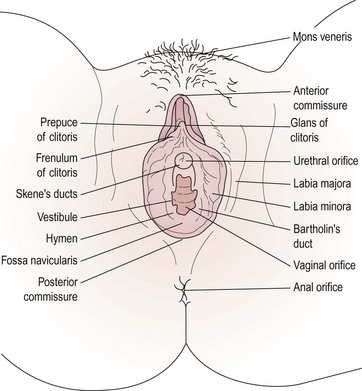

The Vulva

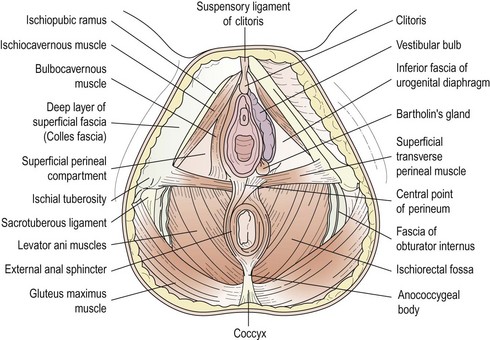

The female external genitalia, commonly referred to as the ‘vulva’, include the mons pubis, the labia majora and minora, the vestibule, the clitoris and the greater vestibular glands (Figure 1.6).

Vestibule

The vestibule is the cleft between the labia minora. The vagina, urethra, paraurethral (Skene’s) duct and ducts of the greater vestibular (Bartholin’s) glands open into the vestibule (see Figure 1.7). The vestibular bulbs are two masses of erectile tissue on either side of the vaginal opening, and contain a rich plexus of veins within bulbospongiosus muscle. Bartholin’s glands, each about the size of a small pea, lie at the base of each bulb and open via a 2 cm duct into the vestibule between the hymen and the labia minora. These glands secrete mucus, producing copious amounts during intercourse to act as a lubricant. They are compressed by contraction of the bulbospongiosus muscle.