(1)

Department Obstetrics & Gynaecology, St George Hospital, Kogarah, New South Wales, Australia

Abstract

Prior to the late 1960s, patients who leaked when they coughed usually underwent an anterior colporrhaphy (anterior repair) with a bladder neck buttress. Urodynamic testing was not commonplace until the late 1970s.

Introduction

Prior to the late 1960s, patients who leaked when they coughed usually underwent an anterior colporrhaphy (anterior repair) with a bladder neck buttress. Urodynamic testing was not commonplace until the late 1970s.

Once urodynamic studies were introduced, it was realized that coughing can provoke a detrusor contraction. Thus, many women who underwent anterior repair did not obtain cure (because they had an element of detrusor overactivity). This poor success rate was one of the reasons that gynecologists became interested in performing urodynamic tests (to improve their surgical cure rates) and was one stimulus to the establishment of urogynecology as a subspecialty.

Once a diagnosis of urodynamics stress incontinence has been made, without substantial voiding difficulty, any detrusor overactivity has been thoroughly treated; then this chapter describes the surgical options available.

Bladder Neck Buttress

This procedure is still used in highly selected cases. For example, if a woman mainly complains of prolapse due to cystocele but is found to have a minor element of stress incontinence on urodynamic testing, then it may be reasonable to perform this procedure. This is particularly true if an elderly woman with prolapse and stress incontinence is found to have an underactive detrusor at urodynamics; one may counsel her that a simple repair with buttress for her stress incontinence is not likely to cause voiding difficulty. The evidence for this comes from retrospective case series, rather than randomized controlled trial [13].

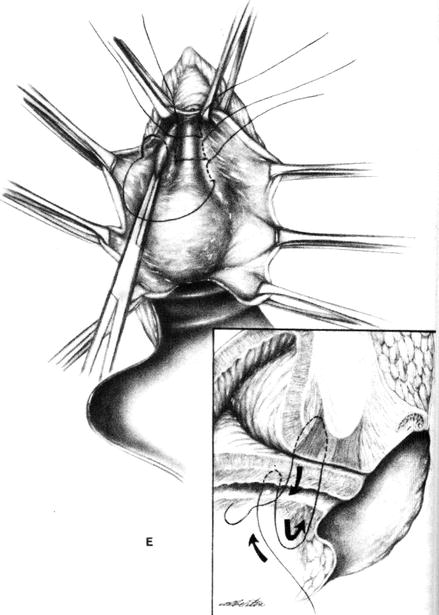

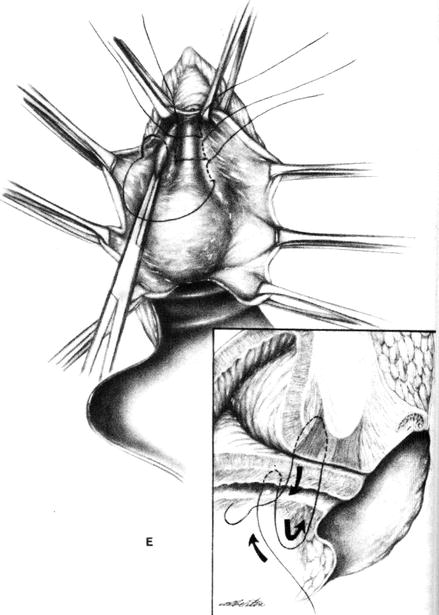

The bladder neck buttress involves the following (see Fig. 9.1):

Figure 9.1

Bladder neck buttress procedure. The sutures pass deeply through the periurethral endopelvic fascia on the posterior aspect of the symphysis pubis (arrow) (Reprinted with permission from Thompson and Rock [28])

Inject local anesthetic with adrenaline into subcutaneous plane.

Insert urethral catheter with 5 ml balloon (to delineate urethrovesical junction).

Dissect vaginal epithelium off the bladder and proximal urethra.

Use a small needle with 1 Vicryl or nonabsorbable suture.

Place three mattress sutures at the bladder neck and proximal urethra to plicate (or buttress) the periurethral fascia that borders the levator hiatus.

The goal is to assist closure of an open bladder neck, but if done correctly, it will also elevate the urethrovesical junction in the retropubic space. This procedure was first described by Kelly in 1913, who reported an initial subjective success rate of 90 %, but this decreased to 60 % subjectively continent over 5 years.

For further details of associated anterior repair for cystocele, see Chap. 10 (prolapse). For postoperative management of voiding function, see “Colposuspension” below.

Colposuspension

From about 1970 until the late 1990s, the most common procedure for USI was the colposuspension. This is still a very useful procedure if the patient requires an abdominal procedure for some other reason.

The procedure is mainly indicated for USI in the presence of urethral hypermobility. If previous surgery has created a fixed, nonmobile urethra, consideration should be given to performing an abdomino-vaginal sling or injecting collagen (but see discussion of TVT). The colposuspension is also highly effective in correcting cystocele.

Preoperative Consent Discussion

Before consenting a patient for colposuspension, ensure that she understands fully the 5–15 % risk of developing de novo detrusor overactivity. Patients can be very distressed if they have an operation because they leak when they play tennis but afterward have to void frequently and leak with unpredictable urge, not to mention nocturia. Such angry patients are commonly referred to a tertiary urogynecology unit!

Also, ensure that the patient understands the 2–5 % risk of longer-term voiding dysfunction (with approximately 0.5 % risk of clean intermittent self-catheterization, CISC). Some urogynecologists ask the patient to meet with a nurse continence advisor to explain CISC before carrying out the operation.

Postoperative Convalescence

This is similar to abdominal hysterectomy, for example, the first week at home should be spent in quiet leisure (reading books, watching TV, etc.). The next 5 weeks are “light duties” (including driving locally, ordinary shopping, with regular rest periods). At 6 weeks, normal activity resumes (including intercourse, swimming, light gym exercise) but with no heavy lifting for a further 6 weeks.

Patients want to know the chance of failure. Objective success rates depend very much on the outcome measure chosen. The original series by Burch [5] revealed a cure rate of 93 % (n = 143) at approximately 2 years, as judged by a stress test at 250 ml and a lateral X-ray with a metal bead chain in the urethra (to look for stress leak or an open bladder neck). The cure rate at a mean of 14 years follow-up (range 10–20 years, n = 109) was 80 % on 1-h pad testing [2].

The Technique of Colposuspension

This involves the following (see Fig. 9.2):

Place a 14–16-gauge catheter (easy to feel vaginally) in the urethra.

Inflate 5-ml balloon (30-ml balloon is too big, will get in the way).

Make a Pfannenstiel incision.

Access the retropubic space (the Cave of Retzius).

By careful dissection (to avoid large veins in this region), expose the back of the pubic bone and the lateral aspects of the urethra.

The right-handed operator double gloves and places the left hand in the vagina.

With fingers on either side of the catheter in the vagina, define the urethrovesical junction (at the balloon).

Place three Ethibond J-shaped sutures on either side of the urethrovesical junction.

Attach each suture to the iliopectineal ligament at the back of the pubic bone.

With the surgeon’s left hand lifting up the vagina, the assistant ties the sutures onto the iliopectineal ligament.

The surgeon dictates the degree of tension so as not to overcorrect (tissue should not be taut, just comfortably elevated).

Insert a drain to the retropubic space.

Insert suprapubic catheter and empty the bladder (no vaginal pack).

Immediate Complications of Colposuspension

Hemorrhage into the retropubic space, with a transfusion risk of about 0.5 %

Trauma to the bladder (inadvertent cystotomy) requiring repair and subsequent urethral catheter for 7–10 days, approximately 2–3 %

Long-Term Complications of Colposuspension

Figure 9.2

Three permanent sutures are (a) placed through the endopelvic fascia on each side of the urethra and (b) passed through the iliopectineal ligament of Cooper

Postoperative Management for Colposuspension

Free drainage of SPC for 36–48 h; patient unlikely to void due to pain of incision over this time frame.

Commence trial of void at approximately 36 h, if patient is ambulant.

Once residual volumes is less than 100 ml on three consecutive occasions, usually by day 5 post-op, remove suprapubic catheter.

Double Voiding Technique

If residuals are gradually getting lower but still not <100 ml at day 4–5, teach patient to:

Void the first time in normal position.

Stand up and rotate the pelvis a few times to stimulate the afferent nerves.

Sit down and lean forward with elbows on knees.

“Drop” or purposefully relax the pelvic floor muscles.

Remain so for 2–3 m, perhaps read a magazine, and await further flow.

This often will produce another 50–100 ml, sufficient to give residual <100.

How to Manage Short-Term Voiding Difficulty

Note that the literature often does not define what is meant by “voiding difficulty.” In this text, “short-term voiding difficulty” means the management of a temporary suprapubic catheter (SPC), or self-catheterization, for up to 4 weeks. “Long-term voiding dysfunction” means that the temporary SPC required removal, and thus CISC was instigated, from 4 weeks to permanently.

If patient is not voiding to completion by fifth postoperative day and not suffering from persistent wound pain (hematoma/ infection), able to defecate fully (no impacted feces or perineal pain from other repair), urine is not infected, double-emptying technique is being used, but otherwise well and ready to plan discharge from hospital:

Discard the drainage bag.

Attach a Staubli valve or Flip Flow valve (Fig. 9.3) to the SPC.

Figure 9.3

Witches’ hat urine collection device and Staubli/Flip Flow valves

Teach patient to record own voided volumes and residual volumes on chart.

After training for 12–24 h, using a “witches’ hat” graduated collecting device placed in the toilet (Fig. 9.3).

Send her home for 3 or 4 days to continue trial of void in home toilet.

Review back in clinic in 3 or 4 days with her residual volume chart.

Majority of patients will void well with this method.

How to Manage Long-Term Voiding Dysfunction

If unable to void after 2–3 weeks of home trial of void, the SPC site will become inflamed and painful.

If patient is almost voiding normally, flucloxacillin 500 mg TDS may help to preserve the SPC for a few more days.

After this, patient should be trained in clean intermittent self-catheterization (CISC), by a specialist nurse continence advisor because the SPC site will become inflamed.

Follow-up with a voided volume and residual chart, kept for 24 h prior to each visit, should be every 2 weeks thereafter. If the bladder is kept well emptied by CISC, spontaneous resolution of the voiding dysfunction often occurs over 3 months.

Bad prognostic features are:

Patients with previous pelvic radiotherapy

Patients taking psychotropic drugs with anticholinergic properties

Patients who have undergone radical bowel resection with denervation of pelvic nerves

The Abdomino-Vaginal Sling

Also known as the pubovaginal sling, this procedure is the time-honored operation for patients with previous failed continence surgery, particularly if:

There is persistent hypermobility on vaginal examination and videourodynamics (VCU).

If the urethra is fixed in the retropubic space (on VE and VCU) but the urethra closure pressure is low (below 20 cm) or the Valsalva leak point pressure is low (below 60 cm), then the abdomino-vaginal sling is worthwhile.

Note that if the urethra is fixed in the retropubic space but the urethral closure pressure or Valsalva leak point pressure is normal, then collagen/Macroplastique injections may be worthwhile; see later section this chapter.

Preoperative Consent Discussion

This discussion is similar to that for the colposuspension, except that risk of voiding difficulty/dysfunction is probably higher, mean of 12.5 % (range 3–32 %); risk of de novo detrusor overactivity is similar (mean risk 10 %, range 4–18 %). The objective success rate after previous failed procedures is 86 % (all data from Jarvis [13]).

After a procedure involving a Pfannenstiel incision and a vaginal incision, the first “quiet” week of the convalescence period should probably increase to 2 weeks, but light duties should still be appropriate at 6 weeks.

The abdomino-vaginal sling procedure entails the following (see Fig. 9.4):

Figure 9.4

(a) Harvesting a strip of rectus abdominus fascia 13 × 2.5 cm. (b) Placement of autologous sling under urethra and then attachment to rectus abdominus under minimal tension

Insert 16-G Foley catheter into bladder with 5 ml balloon.

Make a wide Pfannenstiel incision.

Harvest a strip of rectus abdominus fascia 13 × 2 cm; wrap in moist gauze.

Dissect down to the retropubic space as for a colposuspension.

From below, incise the anterior vaginal wall as for an anterior repair but should only need to dissect about 3 cm below the urethrovesical junction.

Working on a flat sterile surface; insert nylon 1.0 sutures to the four corners of the rectus sheath strip.

Insert a long narrow Bosman’s packing forcep downward from the retropubic space into the vagina, emerging at the urethrovesical junction (guided by the balloon of the catheter).

Bring the nylon sutures attached to the strip of sheath up into the abdominal wound (first on the left, then on the right).

Place the fascia strip under the urethrovesical junction.

Apply 2.0 Vicryl tacking sutures to the fascia at the edges of the vaginal wound to maintain the position of the strip at the urethrovesical junction.

Lift the nylon sutures into the abdominal wound so as to place the fascial strip just under the urethra, with absolutely no tension.

Tie the nylon sutures at the four corners of the strip to the rectus abdominus fascia.

Close the abdominal and vaginal wounds in the traditional fashion.

Insert SPC. Insert drain to the retropubic space. Pack is not mandatory.

Postoperative management is as for a colposuspension. Some surgeons perform this sling procedure using artificial mesh, but most prefer to harvest the patient’s own (autologous) fascia. The relative risk of mesh erosion using artificial mesh has not been well published; there are no randomized trials.

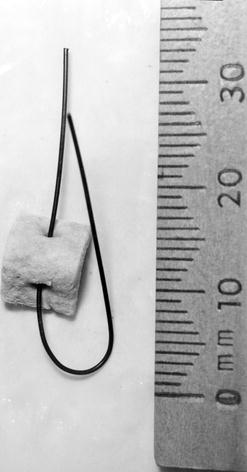

Historical Note: Stamey Needle Suspension and Raz/Pereyra/Gittes Procedures

In 1973, Stamey described a minimally invasive procedure to correct stress incontinence. This involved two passages of a long needle behind the pubic bone; after the first pass, a polypropylene suture was threaded through the needle. An arterial graft pledget was threaded onto the vaginal end of this suture (Fig. 9.5). A second pass of the needle brought the suture back up behind the pubic bone, capturing a thick bridge of periurethral tissue; the suture was tied over the rectus sheath (then repeated on other side). The Raz, Pereyra, and Gittes modifications did not use the nonabsorbable pledget.