3.10 Sudden unexpected death in infancy

• A sudden unexpected death in infancy (SUDI) is one not anticipated 24 hours before death occurred.

• All SUDI deaths must be referred to the coroner for investigation.

• After autopsy, an explanation will be found for some SUDI deaths.

• If no explanation is found after examining the circumstances of death, the clinical history and the autopsy findings, the diagnostic label sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) may be used.

• Parents of SUDI infants should be offered follow-up with a clinician who can discuss the autopsy and other findings in regard to their child’s death.

• Advising new parents to sleep their infant supine in a safe sleep space and to avoid smoking in pregnancy are important ways to prevent SUDI.

• A safe sleep space is one designed to make sure that the face is always clear, that there are no risks of wedging or strangulation and that enables a baby to maintain thermal balance.

Incidence and risk factors

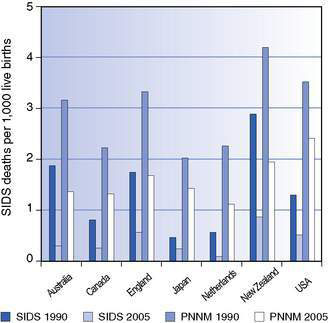

As can be deduced from the discussion above, the problems of definition make comparisons over time and between countries problematic! Figure 3.10.1 shows both SIDS mortality and total post-neonatal mortality in 1990 (before risk reduction campaigns in these countries) and in 2005, 15 years later.

• prone and side sleep position

• maternal smoking during pregnancy as well as postnatal second-hand smoke

• unsafe sleeping environments – especially parents falling asleep with their baby on the same sleeping surface, or in unusual sleeping places such as sofas

• bedding arrangements that allow the face to become covered.