(1)

Department Obstetrics & Gynaecology, St George Hospital, Kogarah, New South Wales, Australia

Abstract

If a patient has a main complaint of frequency/urgency/nocturia/urge incontinence on history or if urodynamic testing has revealed detrusor overactivity, then bladder training is an essential part of treatment. Most continence clinicians would not prescribe anticholinergic drugs without teaching bladder training first.

If a patient has a main complaint of frequency/urgency/nocturia/urge incontinence on history or if urodynamic testing has revealed detrusor overactivity, then bladder training is an essential part of treatment. Most continence clinicians would not prescribe anticholinergic drugs without teaching bladder training first.

Explain the Condition

This is the first step. Many patients with this problem think that they are “neurotic”; often they are an embarrassment to their families as they frequently need to rush to the toilet at social occasions. In fact, during the 1970s and 1980s, several studies suggested that this condition was largely psychosomatic, but conclusive evidence of this was not found.

Since the introduction of quality of life testing in the 1990s, we have learned that patients with detrusor overactivity have a much poorer quality of life than those with stress incontinence and are more anxious and depressed because of the unpredictable nature of their condition.

Recent studies have indicated that:

The subepithelial nerves are overabundant in this condition (increased by about 35% compared to controls [24]; see Fig. 7.1), and neuropeptides involved in conveying “nociceptive” or painful symptoms are increased by 80–90% [32].

Figure 7.1

Increased subepithelial nerves in detrusor overactivity patient

The ability of the cerebral cortex to inhibit the desire to void is reduced in this condition but can be strengthened by training. Functional MRI studies performed during urodynamics show changes in cerebral blood flow in OAB [17].

The detrusor muscle is overly contractile, giving rise to “muscle cramps” in the bladder. Pharmacological studies show that, in the organ bath, the muscle strips from these patients do not relax entirely when atropine is administered (whereas detrusor strips from control patients do relax after atropine is applied). (For review, see Kumar et al. [22]).

Stretch of the bladder causes more rapid release of ATP (a signaling molecule that activates afferent nerves) in patients with OAB compared to controls [10].

Therefore, the patient must understand that she is not neurotic but has an abnormality of the afferent (subepithelial nerves) and efferent (detrusor contractility) limbs of the micturition reflex.

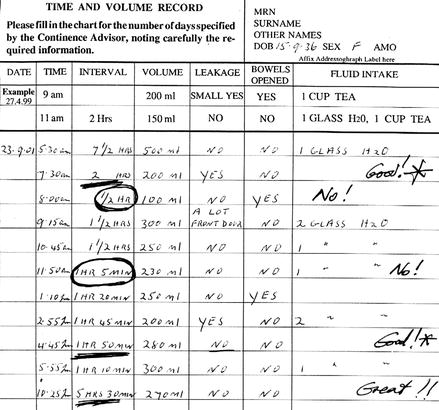

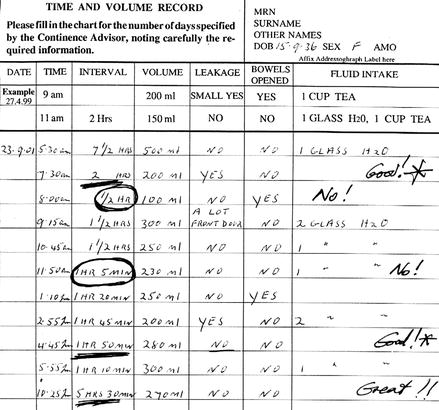

The next step in bladder training is to look at the frequency–volume chart with the patient. Because severity of frequency varies in this condition, the therapist needs to find a realistic target “voiding interval” toward which the patient can aim. For example, if the chart shows that the patient usually toilets every hour but sometimes can hold for 2 h, then the target voiding interval should be 2 h (Fig. 7.2).

Figure 7.2

A typical example of a patient with OAB, with the usual voiding frequency circled and the “target” voiding interval underlined

Once the target (e.g., 2 h) is chosen, the instructions to the patient are as follows.

Step-by-Step Guide to Bladder Training

When you get a desire to go to the toilet, look at your watch.

If it is more than 2 h since you last went to the toilet, just go ahead and pass urine.

If it is less than 2 h since you last went, then you need to do three things:

A. Sit down.

The reason for this is that the bladder has gravity nerves inside the wall that give you a stronger desire to toilet when you are standing than when you are sitting.

B. Contract your pelvic floor muscle (PFM).

The reason is that you must stop any drops of urine escaping from your bladder into your urethra. Once the fluid gets into your urethra, there is an automatic reflex that will make you start passing urine onto your pad, so you need to “nip this in the bud.”

C. Send a strong message from your brain, down your spinal cord to the level of the tailbone, then out to your bladder, saying, “No, I am not going to the toilet for 2 minutes.” There is a direct pathway from the front of your brain, down the spine, to the bladder, but in your condition, the message signals on this pathway seem to have become “rusty” or weak. These messages can be strengthened by focused concentration.

Sit quietly for 2 min, contracting your PFM. At the end of 2 min, stand up (contracting your PFM as you stand), and walk slowly to the toilet (do not run or you are more likely to leak).

However, if you have waited 2 min, it is likely that you will no longer want to go.

This is because the bladder spasms that cause your leakage are like a muscle cramp; they normally only last 1–2 min, and then the muscle cannot hold the spasm any more; it relaxes.

Therefore, you may be able to hold on for another half an hour or so, until another spasm occurs. If this happens after you have successfully stopped the previous spasm, then you should go ahead and walk to the toilet for this one.

Before the patient can successfully undertake step B, she must be examined to make sure that she can contract her PFM, and if not, undergo a program of pelvic floor muscle training, as described in Chap. 6. Do not disappoint the patient by expecting her to succeed with bladder training until she has learned how to contract the pelvic floor muscle.

The patient needs to understand that bladder training is an essential part of treating the overactive bladder. If drugs are prescribed for this condition, they will help to relax the bladder spasms, but the patient must try to inhibit the premature desire to void.

Also, if a patient suffers from nocturia, the bladder training works to increase her bladder capacity during the day. Gradually, her bladder capacity will also increase at night. She must attempt to inhibit the desire to void at night if she is awakened by a snoring husband or a dog that is barking. She must avoid nocturnal trips to the toilet out of habit.

Is bladder training of proven efficacy? Unfortunately, bladder training was introduced before the era of evidence based medicine. An often quoted paper from 1980 set the stage. In it, 25 women had inpatient bladder drill, and 25 women had drug therapy (with imipramine and an outdated drug flavoxate). Of the bladder drill group, 76 % “were rendered symptom free,” versus 48 % of those given drugs [21]. In the same year, outpatient bladder drill was reported to achieve subjective cure in 87% and objective cure in 53% of 90 women [15]. Since then, there has never been an adequately powered trial comparing bladder training with no therapy, but most clinicians find that bladder training is important.

How Do Anticholinergic Drugs Work?

Anticholinergic drugs work through the parasympathetic nervous system; they are antagonists that work at the muscarinic receptor to inhibit (and in some cases abolish) detrusor muscle contractions. For the patient, this can be likened to a muscle relaxant acting on the bladder. There are several types of anticholinergic drugs, with varying pharmacological properties.

Propantheline (Pro-Banthine): 15 mg TDS is a very old antimuscarinic drug. As it is a quaternary amine, it is poorly absorbed from the gut. Side effects of dry mouth and constipation are ubiquitous, but the drug is cheap.

Oxybutynin (Ditropan): Maximum 5 mg TDS has been used since the 1970s. It is an antimuscarinic drug but also has local anesthetic properties (thus, it can be given intravesically) and also a smooth muscle relaxation effect. It is very effective in reducing detrusor contractions, but about 60% of patients will get annoying dry mouth/dryness of the esophagus/difficulty swallowing and stop taking it. It is very cheap. When giving oxybutynin, titrate the dose against the symptoms. For severe nocturia but less daytime leak, give 2.5 mg mane and 5 mg nocte. Some patients are worse in the morning but have no nocturia; give 5 mg mane and 2.5 mg after lunch. The drug works within 1 h and lasts 6–8 h. A long-acting “slow-release” form of oxybutynin has been developed but is not marketed in all countries; this gives less dry mouth (about 25%). A transdermal patch Oxytrol also gives less side effects by avoiding production of a liver metabolite, but pruritus at the patch site occurs in about 7% [27].

Imipramine (Tofranil): 25–50 mg nocte, is also a very old drug. In much larger doses (75–100 mg daily), it is an antidepressant. It has a beta-mimetic action to relax the dome of the bladder but also has anticholinergic effects. Because a common side effect is drowsiness, it is very useful for nocturia. It also lowers the pain threshold by an uncertain mechanism and can be used when the bladder spasms are appreciated as painful (or in painful bladder syndrome; see Chap. 12).

Tolteridine (Detrusitol): 2 mg BD, was developed in the 1990s. It attaches to the bladder muscarinic receptors to a much greater extent than to such receptors in the salivary glands, so it gives less dry mouth than oxybutynin but is just as effective. It also has a slightly longer duration of effect, hence the BD dosage. In some patients, 4 mg BD can be given without dry mouth. A slow-release form has been made which is somewhat more effective with even less dry mouth but is not available in all countries.

Propiverine (Detrunorm): 15 mg TDS, is an antimuscarinic agent that is also a calcium channel blocker. Dry mouth occurs in about 20% of patients but is not usually distressing. It is not available in many countries.

Trospium (Regurin): 20 mg BD, is a nonselective quaternary amine but does not give as much dry mouth (4%). Its structure also limits blood–brain barrier penetration, thus reducing CNS effects in the elderly (confusion). It is widely used in the United Kingdom.

Darifenacin (Enablex, Emselex): selectively acts at the M3 receptor, which is thought to be most functionally important for mediating detrusor contractions, available in most countries.

Solifenacin (Vesicare): 5–10 mg daily, is also selective for the M3 receptor and also does not attach well to the salivary gland receptors. It was developed in early 2000s and achieved continence in 51% of one trial, with 11% suffering from dry mouth, available in most countries.

Fesoteridine (Toviaz): 4–8 mg daily, is the most recently developed anticholinergic, which was derived from tolteridine. It is available in the UK and Europe.

Duloxetine: This is a recently developed serotonin reuptake inhibitor that also affects Onuf’s nucleus in the pelvic nerve plexus. It was designed for the medical treatment of stress incontinence because it enhances the strength of the internal urethral sphincter mechanism. Because it also enhances bladder capacity, it has also been used in overactive bladder. It is licensed in Denmark for use in incontinence.

Desmopressin (Minirin): Consider treating with this if nocturia cannot be helped by other agents. This synthetic vasopressin analogue markedly reduces the production of urine for about 6 h. It is given as 1–2 nasal sprays to each nostril before bedtime; oral tablets are also available. It is useful for patients with debilitating nocturia who are practicing bladder training during the day but have not yet improved their bladder capacity, so they have not yet seen any reduction in nocturia. It is not a good long-term strategy. Particularly in the elderly, prolonged use is associated with hyponatremia that can be life threatening. Be very careful in patients with nocturnal polyuria, however (defined as passing more than 30% of total urine output at night). This drug is contraindicated in such patients so a frequency volume chart must be completed before starting this drug. In children with bedwetting, long-term usage has been shown to be safe.

Are Anticholinergic Drugs Effective?

This is controversial. Most pharmacotherapy trials only consider efficacy at 12 weeks or thereabouts. An initial Cochrane meta-analysis [20] found that, in a review of 6,713 patients in 51 studies, the placebo effect was much higher than expected (about 45 % with respect to control) but that the drugs gave an additional 15% over placebo. Overall, anticholinergic drugs achieved one less leak per 48 h and one less void per 48 h, with respect to placebo. This may seem like a small effect, but most of these trials did not include formal bladder training programs, so they do not reflect ordinary clinical practice. The most recent Cochrane review of 61 trials (11,956 adults) concluded that anticholinergic drugs produce a statistically significant improvement in symptoms of overactive bladder [27].

The natural history of detrusor overactivity has received little attention. Recently, a review of 76 patients with proven DO at a median of 6 years [26] found that symptoms had largely resolved in only about 16 %. Symptoms were no different in 59% of patients and were worse in the remaining 25% (Fig. 7.3). Thus, some form of long-term anticholinergic therapy may be needed in up to three quarters of patients.

Figure 7.3

Histogram showing course of disease in 76 patients with detrusor overactivity at a median follow-up of 6 years (Data from Morris et al. [26])

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree