14 Sleep and Rest

Insufficient sleep affects and is affected by many areas of child and family well-being, including physical and mental health issues. As noted in Box 14-1, many behavioral, mental health, and family problems can be related to sleep problems (Smaldone et al, 2009). Pediatric sleep problems may also produce sleep deprivation and stress in the caregiver(s). As with all other primary care problems in pediatrics, the provider must be vigilant for a myriad of potential causes.

BOX 14-1 Etiology of Sleep Problems in Children

Sleep problems may result from a variety of other problems, including the following:

Normal Sleep Stages and Cycles

Normal Sleep Stages and Cycles

Circadian Rhythms and Establishment of Normal Sleep Patterns

Melatonin secreted by the hypothalamus is responsible for the timing of physiological processes, including the sleep-wake cycle. Light suppresses melatonin production, and darkness is associated with the highest melatonin levels. In normal humans melatonin begins to rise when the sun sets, peaks at 2 am, and falls to almost undetectable levels in the daytime. The day-night melatonin cycle is established between 4 and 6 months old. Levels peak at ages 1 to 3 years and then decline with age. Maternal melatonin crosses the placental barrier and is secreted in breast milk. Prolactin, growth hormone, and testosterone are also on circadian rhythm patterns with maximal secretion at night (Stevens, 2008). Growth hormone appears to be secreted in larger amounts during stages III and IV of sleep (Rodriguez, 2007).

Sleep Cycle

Sleep Cycle Processes

Two main processes are theorized to regulate sleep and wakefulness. The circadian process dictates sleep and wakefulness based on an internal rhythm related to a light-dark cycle. The homeostatic process requires the body to build a need for sleep while awake and as the sleep need is satisfied through sleeping, to build a need for wakefulness. The longer one is awake, the greater the drive for sleep and vice versa.

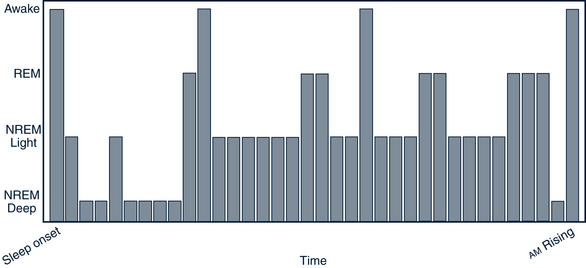

Sleep onset is the time when the person enters stage I NREM sleep. The sleep period begins with sleep onset and continues until full arousal occurs. The sleep cycle includes the repeated episodes of NREM and REM sleep of the sleep period. Waking involves full alert and recall after the sleep period. Semi-wakefulness or alerting to the immediate environment occurs easily in REM sleep or stages I or II in NREM sleep. The REM phase becomes more pronounced later in the evening (Fig.14-1).

Duration of Sleep

Children need more sleep time than adults but gradually achieve adult sleep patterns the older they become (Rodriguez, 2007). Sleep requirements over a 24-hour period vary widely and change as children mature. The typical neonate sleeps 16 hours each day, but some may require up to 18 hours of sleep per day. One third of this is daytime sleep. The longest neonate sleep period is 2.5 to 4 hours and can occur at any time during the 24-hour day (Dewar, 2008c). By 3 months, the baby sleeps almost 15 hours, but the sleep times are more clearly organized into daytime wakefulness and nighttime sleep with a 5-hour period of consistent nighttime sleep (Jenni et al, 2006). Most 6-month-old infants sleep through the night and have morning and afternoon naps. At 1 year most children sleep about 13.9 hours. The morning nap is generally given up between 12 and 24 months, but the afternoon nap may persist until the child is 4 or 5 years old. By 2 years the child is probably sleeping 11 to 12 hours at night with a 1- to 2-hour nap after lunch. Five-year-olds sleep 11 hours per night on average. Four- to 6-year-olds generally have an 8 pm bedtime and 7 am wake time on weekdays and slightly later bedtimes on weekends (Touchette et al, 2008). The average sleep requirement for adolescents is believed to be about 8 to 9 hours per night (Table 14-1) (Dewar, 2008b,c; Jenni et al, 2007; Rodriguez, 2007).

TABLE 14 -1 Average Sleep by Age

| Age | Nighttime Sleep (hr) | Daytime Sleep (hr) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 week | 8.25 | 8.25 |

| 1 month | 8.5 | 7 |

| 3 months | 10 | 5 |

| 6 months | 11 | 3.4 |

| 9 months | 11.2 | 2.8 |

| 12 months | 11.7 | 2.4 |

| 18 months | 11.6 | 2 |

| 2 years | 11.4 | 1.8 |

| 3-5 years | 12.5 | |

| 5-11 years | 11 | |

| 12-17 years | 8-9 |

Adapted from Dewar G: Baby sleep requirements: a guide for the science-minded parents, 2008b. Available at www.parentingscience.com/baby-sleep-requirements.html (accessed Jan 10, 2010); Dewar G: Newborn sleep patterns: a guide for the science-minded parents, 2008c. Available at www.parentingscience.com/newborn-sleep.html (accessed Jan 10, 2010); Jenni O, Molinari L, Caflisch J, et al: Sleep duration from ages 1 to 10 years: variability and stability in comparison with growth, Pediatrics 120:769-776, 2007; Rodriguez A: Pediatric sleep and epilepsy, Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 7:342-347, 2007.

Sleep Issues

Sleep Issues

Co-Sleeping Issues

Sleep habits are strongly influenced by culture. Co-sleeping is common in many cultures and has been the human norm for thousands of years. Co-sleeping by family members is probably more common worldwide than is separate sleeping as advocated in the U.S. Warmth, protection, and a sense of well-being are undoubtedly facilitated by having babies sleep with their mothers or siblings (Dewar, 2008a,b). One of the greatest advantages of co-sleeping is the facilitation of breastfeeding. Parents of co-sleeping infants report that not only is breastfeeding improved, but parental sleep and parent-infant bonding is as well, and there is a decrease in nighttime infant crying (Goldberg and Keller, 2007). It is most common in African-American and Hispanic families. Co-sleeping is also common with absence of one parent from the home. Co-sleeping is not in itself a reason for sleep problems. However, some families allow the child to sleep with the adults because of problems with enforcing bedtimes, anxiety about leaving the child alone, problems with the quality of daytime interactions, or a desire to avoid the spouse. Sexual abuse of the child also needs to be considered (see Chapter 17 for further child abuse discussion). In these cases, intervention may be helpful to the family (Howard and Wong, 2001).

Sleep Positioning

Studies have provided strong evidence that positioning young infants on their backs significantly decreases the incidence of SIDS. The AAP (2005) recommends that all infants sleep in a supine position unless there is some specific medical contraindication to that position. Side sleeping is not recommended. The AAP also recommends use of a crib and avoidance of soft materials in the sleep environment, bed sharing, smoking during pregnancy and afterward, and overheating the infant. Offering a pacifier at sleep times seems to have some effect in reducing SIDS risks (AAP, 2005). SIDS is also discussed in Chapter 38.

Assessment

Assessment

Indicators of Sleep Problems in Children and Adolescents

Adolescents have many problems with sleep that may manifest as excessive sleepiness, difficulties with mood regulation, impaired academic performance, and increased risk for accidents and obesity. These may be related to adolescent changes in sleep physiology and lifestyle habits of the teen years. Chronic sleep deprivation is a common reason for sleepiness in adolescents (Noland et al, 2009). Sleep loss or disturbances have been associated with increased risk of future depression and anxiety in adolescents (Alfano et al, 2009). Noland and associates (2009) identified the risk of adolescent obesity to increase by 80% due to each hour of chronically lost sleep. Sleep deprivation in adults causes poorer high-order cognitive functioning; accidents and poor judgment are outcomes (Stevens, 2008).

History

Pediatric sleep has become a topic of interest with increasing research and attention to sleep issues in children with a variety of health problems. Several child sleep screening tools can be used by clinicians in everyday practice to assess sleep hygiene (Box 14-2) (Lee and Ward, 2005; Sadeh, 2004). Because sleep problems are so common and tend to persist, it is recommended that sleep be addressed at well-child visits, as a component of care of sick children when sleep is likely to be interrupted, and with all children with chronic conditions because so many have associated sleep problems. The normal sleep pattern, the general health history, sleep habits of the parents and family, and the sleep environment are assessed for factors that may affect sleep and rest. Significant sleep problems need to be referred to sleep centers or other specialists.

BOX 14-2 Sleep Screening Tool

Data from Howard B, Wong J: Sleep disorders, Pediatr Rev 22:327-341, 2001; Lee K, Ward T: Critical components of a sleep assessment for clinical practice settings, Issues Ment Health Nurs 26:739-750, 2005; and Sadeh A: A brief screening questionnaire for infant sleep problems: validation and findings for an Internet sample, Pediatrics 113:e570-e577, 2004.