Livedo reticularis

Skin ulcerations

Postphlebitic/Postthrombotic

Livedoid vasculopathy-like

Pyoderma gangrenosum-like

Digital gangrene

Pseudovasculitic manifestations

Purpura

Palmar/plantar erythema and/or cyanosis

Papules/nodules

Malignant atrophic papulosis-like

Extensive cutaneous necrosis

Subungual splinter hemorrhages

Anetoderma

Thrombocytopenic purpura

12.2 Livedo Reticularis

Livedo reticularis (LR) is the most frequently associated cutaneous manifestation in patients with APS, seen as the presenting sign in up to 40 % of patients and observed in up to 70 % of patients who suffer from APS secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [6]. LR is a mottled red or bluish discoloration of the skin with a net-like pattern induced by a vascular disturbance with stagnation of blood in dilated superficial capillaries and venules [2]. It is due to reduced blood flow and lowered oxygen tension at the peripheries of the skin segments. The vascular units in the skin are arranged in inverted cones, supplied by a central arteriole coming perpendicularly from vessels in the fascia: the clinical feature of LR results from deposits of deoxygenated blood at the junction between cones [3]. In the English literature, the term cutis marmorata is used for physiological livedo, characterized by regular, unbroken, symmetrical circles, mainly localized on the limbs of children or young women. It is usually vasomotor with variations depending on temperature. LR refers to all other livedos; the so-called livedo racemosa is characterized by an irregular pattern with broken large branches and is localized not only on the limbs but also on the trunk and buttocks. Histopathology of LR is usually not conclusive because it does not show thrombosis [2, 6]; however, vascular proliferation or endarteritis obliterans of arterioles has been reported [3]. The pathophysiology is unclear but it may be related to interaction of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs) with endothelial cells, leading to endothelial dysfunction and arterial thrombosis [7]. Frances et al. [2] found that LR is more frequently associated with arterial events than venous thrombosis in patients with APS, proposing this skin sign as a useful marker for the arterial subset of APS. No treatment has proven to be effective for LR, which may spread or appear despite anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapies. Considering the high prevalence of arterial thrombosis in patients with LR in the context of APS, it is important to reduce other risk factors such as smoking or oral contraceptives containing estrogen [6].

12.3 Idiopathic Livedo Reticularis with Cerebrovascular Accidents (Sneddon’s Syndrome)

Sneddon’s syndrome is a rare disorder of uncertain pathophysiology, described by Sneddon in 1965 [8]. It is clinically characterized by the association of LR with cerebrovascular accidents, consisting of strokes or transient ischemic attacks. It affects young or middle-aged women, before the age of 45 years. LR, typically occurring on the trunk and buttocks, but also on the extremities and face, may precede the onset of cerebral manifestations by years [7]. Cutaneous manifestations other than LR include acrocyanosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and, less frequently, skin necrosis. In Sneddon’s syndrome, skin biopsy is usually nondiagnostic, because no specific histopathological changes are detected in the majority of cases [4]. However, Zelger et al. [9], studying a large series of LR skin specimens taken from Sneddon’s syndrome patients, found that only small- to medium-sized arteries at the dermal-subcutis edge are involved in a stage-specific pattern. Early lesions are characterized by a lymphohistiocytic endotheliitis with partial or complete occlusion of vascular lumen. In intermediate phase lesions, histology shows proliferating subendothelial cells and dilated capillaries in the adventitia of the occluded vessel, evolving in fibrosis and shrinkage of vessels in the late phase. Two distinct subsets of Sneddon’s syndrome have been categorized: one is aPL related with preferential arteriolar involvement and the other is regarded as a primary non-aPL-related small artery disease, primarily affecting the brain and skin vessels [7]. The relationship between Sneddon’s syndrome and APS is under debate. The reported prevalence of aPLs in Sneddon’s syndrome ranges from 0 to 85 % and some authors have suggested that the positivity of aPLs may identify a subgroup of primary APS [10].

Chronic anticoagulation with warfarin is warranted for patients with Sneddon’s syndrome, although this treatment is not effective for livedo; low-dose antiplatelet therapy with aspirin is frequently used, although its efficacy is not proven [11].

12.4 Skin Ulcerations

Skin ulcerations are a well-known feature in patients with lupus anticoagulant positivity; in a European study on 1,000 patients with APS, the frequency of leg ulcers was 5.5 % and they were the presenting manifestation in 3.9 % of cases [12]. In SLE, 87 % of patients with leg ulcers are anticardiolipin antibody-positive [2]. Different types of skin ulcerations, whose clinical features and pathophysiological aspects are described below, may occur during the course of APS [2–5]

12.4.1 Postphlebitic or Postthrombotic Ulcers

Postphlebitic or postthrombotic ulcers usually manifest in patients with recurrent phlebitis or deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremities. The typical presentation is astasis dermatitis with erythema and edema.

12.4.2 Atrophie Blanche

Atrophie blanche was first described in 1929 by Milian in young to middle-aged woman showing 3–8 mm painful lesions around the malleoli that rapidly progress to punched-out ulcers; these ulcers heal with a porcelain white scar surrounded by telangiectasias, which is termed atrophie blanche. The association with aPLs, particularly in SLE, is frequent [6]. Nowadays, atrophie blanche is not regarded as a distinct entity but as a limited form of livedoid vasculopathy.

12.4.3 Livedoid Vasculopathy

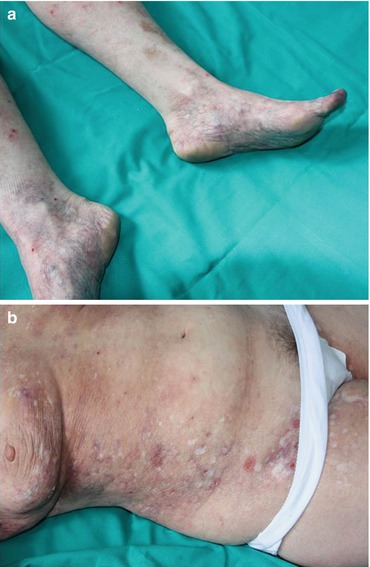

In livedoid vasculopathy (LV), the ulcerations described above usually involve lower extremities (Fig. 12.1a) and resolve leaving the characteristic scars of atrophie blanche (Fig. 12.1b); a rare widespread cutaneous presentation has also been reported [13, 14]. LV may be associated with infections or systemic autoimmune diseases, including SLE and APS, of which it is often the sole manifestation [15], but sometimes no underlying disorder can be detected. The latter, “idiopathic” form of LV is at present considered to be a noninflammatory thrombotic disease due to occlusion of dermal small vessels [16, 17] that may occur in patients with coagulation abnormalities [18–21]. Histologically, LV shows segmental hyalinization, endothelial proliferation, and thrombosis of the upper and mid-dermal small vessels associated with a mild, mainly perivascular, lymphocytic infiltrate. In cases associated with autoimmune disorders, immune-mediated mechanisms are considered to be responsible for vascular damage, leading to a true small vessel vasculitic process. Antiplatelet treatment, such as low dose aspirin, represents the first-line therapy; pentoxifylline, prostacyclin, and anticoagulant agents have also been reported, the last ones particularly for highly relapsing and widespread cases. Immunosuppressive agents, most notably systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporin, are reserved for refractory cases or for cases in which vasculitic changes are seen on skin histology [14].

Fig. 12.1

(a) Mottled bluish discoloration of the skin on the lower extremities in a patient with livedoid vasculopathy. (b) Typical porcelain white scars defined as atrophie blanche

12.4.4 Pyoderma Gangrenosum-Like Ulcers

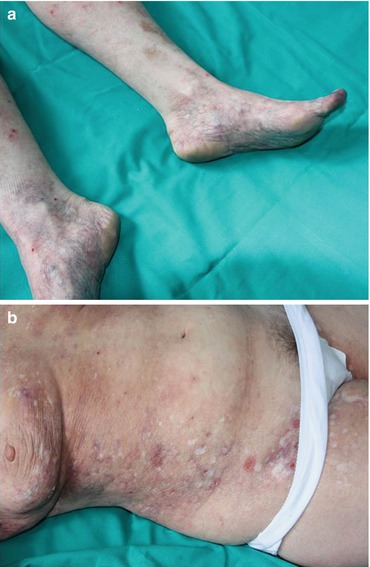

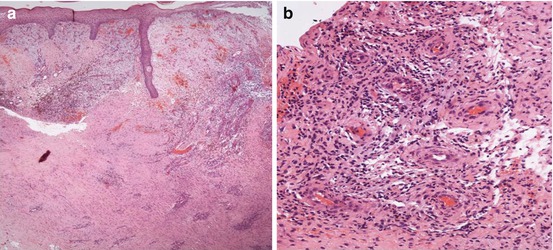

A few cases of ulcerations clinically resembling pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) have been reported in association with primary or SLE-related APS (Fig. 12.2a) [22–24]. The lesion differs from typical PG ulcers (Fig. 12.2b) in lacking violaceous undermined borders and involving also sites other than the legs. PG is a rare skin disease nowadays classified within the spectrum of neutrophilic dermatoses, a heterogeneous group of forms caused by the accumulation of neutrophils in the skin and, rarely, in internal organs [25, 26]. PG is associated with an underlying disease, most commonly inflammatory bowel diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, and hematological malignancies, in around 40 % of cases [27, 28] and is regarded as autoinflammatory in origin [29, 30]. The typical histology of PG is characterized by a mainly neutrophilic dermal inflammatory infiltrate, but it is often not specific; in PG-like APS ulcers, thrombotic changes may be present (Fig. 12.3). The treatment for PG-like APS ulcerations is the same used for PG: topical corticosteroids or tacrolimus for localized cases [31]; systemic corticosteroids alone or in combination with immunosuppressants, notably cyclosporin, for more extensive presentations; and tumor necrosis factor-α antagonists for refractory forms [32].

Fig. 12.2

(a) Ulcerations clinically resembling pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome. (b) A typical PG ulcer with the characteristic violaceous undermined border

Fig. 12.3

Skin biopsy specimens taken from a pyoderma gangrenosum-like ulcer in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome. (a) Histology showing epidermal ulceration and a dense dermal inflammatory infiltrate (haematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification, X20). (b) High-power view showing the mixed, mainly lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, with thrombotic occlusion of dilated dermal small vessels (haematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification, X200)

12.5 Digital Gangrene

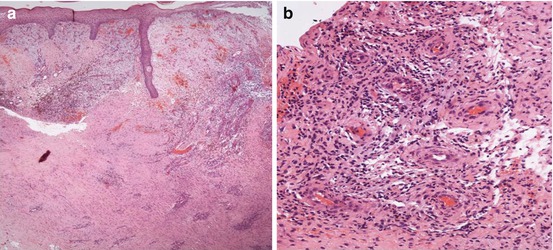

Cutaneous gangrene has been reported to occur in 19 % of APS patients [33]. The prevalence of digital gangrene (Fig. 12.4a) is 3.3–7.5 %, and in 2.5 % of the cases, it is the presenting feature [3, 6]. Gangrene, which may be preceded by distal erythema, cyanotic macules, or pseudo-cellulitis, is caused by occlusion, or sometimes stenosis, of large- or medium-sized vessels. Regarding treatment, anticoagulation therapy is required [2, 7].

Fig. 12.4

(a) Digital gangrene. (b) Purpuric lesions on the legs

12.6 Pseudovasculitis Manifestations

Cutaneous pseudovasculitic lesions represent a group of manifestations that simulate cutaneous vasculitis [2], whose clinical features are typically polymorphic [14]; these pseudovasculitic lesions include: (i) Purpura, frequently necrotic, sometimes evolving in livedoid vasculitis-like ulcers; (ii) small palmar and plantar, erythematous or cyanotic lesions; (iii) papules and nodules on the limbs, ears, neck, and thighs, histologically characterized by thrombotic vessels or vessels containing organized thrombi in the dermis and/or in the subcutaneous tissue [34]. This group includes also lesions mimicking malignant atrophic papulosis. Malignant atrophic papulosis or Degos’ disease is a rare vasculopathic disorder causing occlusion of small- and medium-sized arteries [35]. The skin manifestations are usually the presenting feature, followed by gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system involvement, possibly leading to a fatal evolution. Ocular, cardiovascular and pulmonary changes are also reported [35]. Cutaneous lesions begin as pink or red, dome-shaped papules, 2–5 mm in size, which become necrotic and umbilicated with a central white scar and an edematous telangiectatic border [35]. The pathogenesis of Degos’ disease is still unclear, although viral, autoimmune, and coagulation abnormalities have been suggested to play a role [7].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree