18 Sexuality

Standards

Standards

• Ensuring a confidential environment in which the adolescent and health provider can freely exchange information

• Assessing and providing guidance toward the healthy accomplishment of physical, sexual, social, moral, cognitive, and emotional developmental tasks

• Supporting parental behaviors that promote healthy adolescent adjustment

• Health guidance that promotes wellness and healthy lifestyles, such as responsible sexual behaviors (e.g., abstinence, limiting the number of sex partners, and the modification of sexual practices)

• Education about the use of latex condoms to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and appropriate methods of birth control with instructions on how to use them effectively

• Annual interviews about involvement in sexual and other lifestyle behaviors (e.g., alcohol and drug use) that may result in unintended pregnancy and STIs, including HIV infection

• Questions that explore the adolescent’s sexual orientation, number of sex partners in the previous 6 months, if the individual has exchanged sex for money or drugs, pregnancy, and STI history

• Assessing sexual maturity stages for normal progression

• Educating about breast and testicular self-examinations

• Screening sexually active adolescents for STIs (chlamydia and gonorrhea) and pregnancy and partner notification and referral for treatment. Those initiating sex early in adolescence, those residing in detention facilities, those who attend STI clinics, young men who have sex with men, and those using injection drugs are particularly at risk (Workowski and Berman, 2010).

• Confidential HIV and syphilis screening of adolescents at risk for infection

• Routine cervical cytology screening at age 21 (The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)); or 3 years after the onset of sexual activity (AAP et al, 2010)

• Annual interviews about any history of emotional, physical, and/or sexual abuse by caregivers, friends, or intimate partners

• Initiating the series of hepatitis B vaccinations for those 11 years and older if series not already completed

• Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination (either Human Papillomavirus Bivalent [Types 16 and 18] Vaccine, Recombinant [Cervarix] or Human Papillomavirus Quadrivalent [Types 6, 11, 16, and 18] Vaccine, Recombinant [Gardasil]) for females to prevent cervical cancer and Gardasil for males 9 to 26 years old before their first sexual encounter, if possible. Only Gardasil protects against the HPV types that cause most genital warts in males and females (CDC, 2010).

Normal Patterns of Sexuality

Normal Patterns of Sexuality

Historical and Cultural Context of Sexuality

Contemporary Definitions

Murphy and Elias (2006, p 398) summarize that:

• Gender identity: The knowledge of oneself as being male or female. It is believed to evolve from a combination of genetic, prenatal and postnatal endocrine influences, and postnatal psychosocial and environmental experiences (Hines, 2009; Meininger and Remafedi, 2008; Murphy and Elias, 2006). It usually relates to anatomic sex, but not always (e.g., transgendered persons). One’s gender identity develops in stages according to age stage and cognitive development, which are discussed later. Many theorists argue that gender identity is not fully established until a child has mastered the concept of gender permanency (5 to 7 years old). Others believe gender identity is achieved in the toddler and preschool years. Research of children with complex genital anomalies suggests that genital appearance alone may not be a crucial determinant in the formation of gender identity. In males, genital appearance does not necessarily predetermine their gender identity. In females, prenatal androgen exposure, rather than the degree of evident virilization, proved to be more causal in atypical gender identity (Ahmed et al, 2004; Hines, 2009).

• Gender role: The outward expression of maleness or femaleness; it usually relates to anatomic sex, but not always, such as with transvestites (Frankowski, 2004). This process begins at preschool age and continues into adulthood. It is characterized by the emergence of behaviors, attitudes, and feelings that are labeled as male, female, or neutral. Ahmed and colleagues (2004) suggest that gender role behavior is dependent on testosterone and estradiol exposure. Testosterone levels, measured in amniotic fluid, appear to predict male-typical behavior in childhood. Other behaviors that have been linked to the amount of testosterone exposure prenatally include core gender identity, physical aggression, and empathy (Hines, 2009).

• Gender assignment: Gender assignment generally occurs at birth, based on genital appearance and is the keystone, in many societies, for future gender socialization (i.e., gender identity). In most cases, genital appearance is determined from conception and is based on the 46XX and 46XY chromosome karyotypes and the appropriate masculinization effect of prenatal steroid exposure (testosterone and dihydrotestosterone). In approximately 1 in 4500 births, gender assignment may be difficult to assign at birth as a result of complex genital anomalies. In these cases, chromosomal analysis may be only one step in the process of assigning gender because gonadal dysgenesis can lead to karyotype variations. Also in these cases, gender assignment is done after careful consideration of the pathological conditions of the clinical syndrome (fetal exposure to prenatal steroids and degree of masculinization), long-term psychosexual and psychosocial functional outcome of surgical correction, and androgen support (see Chapter 25).

• Gender attribution: This is a subjective perception of person based on a number of cues (e.g., manner of dress, hairstyle, gait, mannerisms, and choice of occupation).

• Gender, or sexual, orientation: (“Whom do I love?”) refers to an individual’s feelings of sexual attraction and erotic potential. Meininger and Remafedi (2008, p 554) define sexual orientation as:

Stages of Developmental Patterns of Sexuality

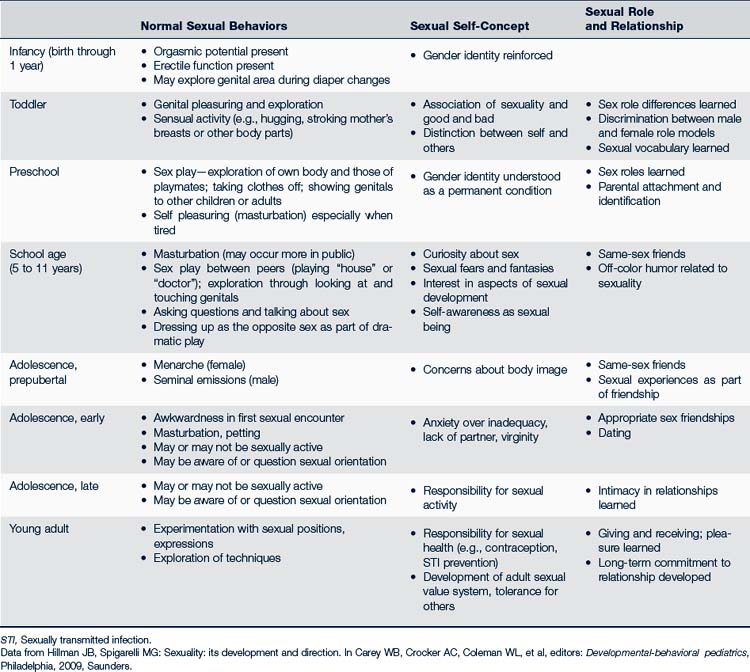

The primary care provider is in a unique position to incrementally educate parents about their child’s sexual maturation starting from infancy and to distinguish between normal and problematic sexual behaviors. Anticipatory guidance will not only enable parents to accurately understand their child’s normal sexual development but also provide a structure for healthy parent-child sexual discussions in an ongoing open manner throughout the child’s life. Table 18-1 discusses the components of development and behavior related to sexuality.

TABLE 18-1 Sexual Behaviors, Self-Concept, and Relationships During Childhood Through Young Adulthood

Two to 5 Years Old

Parents should be encouraged to use the appropriate names for body parts and bodily functions, even though they may also be using slang words. This will enable children to better comprehend discussions with health providers, teachers, or health educators when the anatomical and physiological terms are used.

Five to 9 Years Old

School-age children continue to have a high level of curiosity about sexuality, their bodies, and their environment. They are aware of the pleasure stimulation gives and continue to actively seek autoerotic arousal for enjoyment. Again, reassure parents that this behavior is not associated with sexual fantasies. Contacts with other children may give them new ideas about sex, and sex games are typical (e.g., playing house or doctor) between same-age children, either of the same or opposite sex. This is normal behavior as long as a child is not emotionally distraught by the encounter or if it involves one child who is older than the other. Parents should avoid being overly alarmed if they witness this play. It is appropriate for parents to redirect the play to other activities. They should then discuss the situation later with their child to explore the experience, ascertain if the child was uncomfortable, and again emphasize the notion of privacy and respect for one’s body. Box 18-1 discusses sexual actions beyond self-stimulation and sex play that can indicate possible sexual abuse.

BOX 18-1 Signs That Sexual Play May Go Beyond Normal∗

• The behavior is not age-appropriate.

Example: A 5-year-old walks around the house with his or her hands in his or her underwear.

Example: Child frequently engages in sexual play and rarely moves on to other activities.

• The child looks anxious or guilty or becomes extremely aroused.

• Child is being forced into sexual play through bribes, name-calling, physical force.

• Child knows more about sexual matters than age-appropriate.

∗Most sexual play is accompanied by laughter and lightheartedness (the little girl who giggles when lifting her skirt; the little boy who laughs when he shows you his penis wrapped in a towel).Adapted from Todd CM: Responding to sexual play, Child Care Center Connect 3(5):1-3, 1994, University of Illinois Cooperative Extension Service. Available at www.nncc.org/Guidance/cc35_respond.sex.play.html (accessed Sept 3, 2010).

Sexuality in Individuals With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

The sexual development of youth with intellectual and physical developmental disabilities (I/P/DD) is the same as those without such physical or cognitive limitations. The clinician needs to focus on the developmental level rather than chronological age when determining appropriateness of sexual behavior. For example, an individual with a cognitive level of a preschooler will normally exhibit sexual behaviors consistent with that developmental level.

People with I/P/DD largely acquire their sex education from formal educational programs and the media rather than from family or friends. Females may obtain such education in the form of abuse. These individuals are less likely to share their thoughts, feelings, and experiences with family and friends (Ailey et al, 2003). Unless healthy sexuality is taught and supported, unhealthy and abusive sexuality can occur. Sex education can be effective for those with I/P/DD, and topics should include those listed in Box 18-2. The depth and length of discussion should vary depending on the type of disability (e.g., sex education taught to a child with autism would have a different focus than that taught to a child with Down syndrome). Excellent resources and books for parents, teachers, and clinicians can be accessed from Planned Parenthood, SIECUS, and the National Dissemination Center for Children With Disabilities (NICHCY).

BOX 18-2 Sexual Education Topics for the Individual With Intellectual and Physical Developmental Disabilities

Concepts of privacy and choice

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

Sexual responsibility and privileges, and consent

Data from Ailey SH, Marks BA, Crisp C, et al: Promoting sexuality across the life span for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, Nurs Clin North Am 38:229-252, 2003.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree