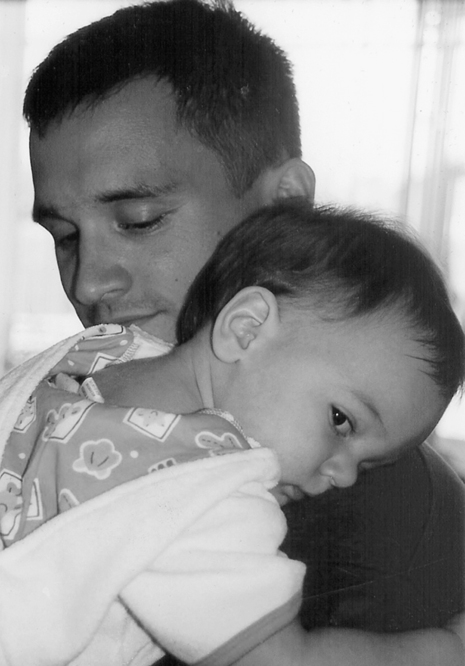

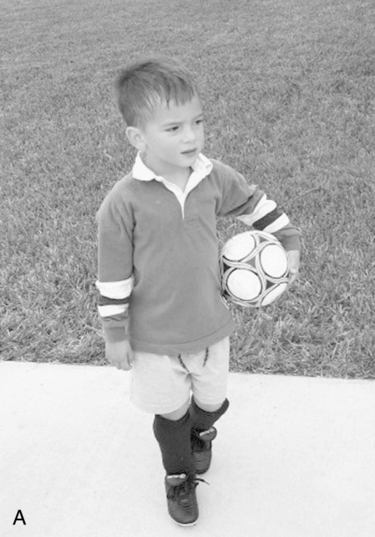

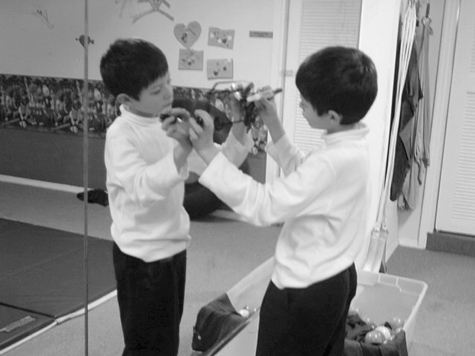

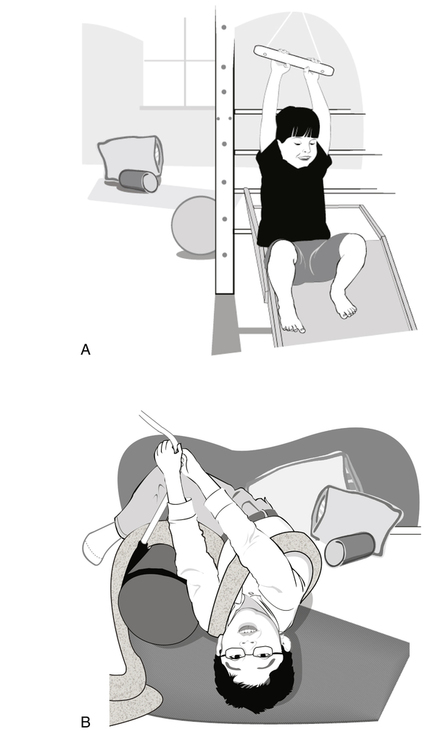

24 RICARDO C. CARRASCO and SUSAN STALLINGS-SAHLER After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following: • Define the basic principles underlying sensory integration theory, assessment, and treatment • Review sensorimotor, perceptual motor, environmental adaptations, and other approaches used in alleviating sensory processing disorders • Understand the role of the certified occupational therapy assistant in working with children who have sensory processing disorders • Define sensory modulation disorder • Describe sensory modulation observational assessment and intervention strategies • Describe sensory discrimination intervention strategies • Understand the types of sensory-based movement disorder and intervention strategies • Identify/describe intervention methods for children who have postural–ocular and bilateral integration dysfunction • Identify/describe intervention techniques to work with children who have developmental dyspraxia The term sensory processing refers to the means by which the brain receives, detects, and integrates incoming sensory information for use in producing adaptive responses to one’s environment. Children who have sensory integrative dysfunction have a cluster of symptoms that are believed to reflect dysfunction in central nervous system (CNS) processing of sensory input rather than a primary sensory deficit such as hearing or visual impairment; a frank CNS insult such as cerebrovascular accident (CVA, or stroke) or traumatic brain injury (TBI); or even deficits that come from chromosomal or genetic abnormalities such as Down syndrome. The disorder leads to disorganized, maladaptive interactions with people and objects in the environment. Such interaction, in turn, produces distorted internal sensory feedback, which reinforces the problem.5 However, there are several subtypes of sensory processing dysfunction. Whereas individuals with SI dysfunction (or those with sensory processing dysfunction) share many similarities, they do not all appear alike. Children with the disorder often have a primary diagnosis such as autism, learning disability, or attention deficit disorder; or psychogenic comorbidities related to anxiety, panic, or attachment disorder. Also, a range of levels of severity, from mild to quite severe, exist. In some children, sensory processing dysfunction may lead to disabling learning problems, causing academic failure.5 In others, it may be reflected in clumsiness and the struggle of the child to perform everyday occupations that others take for granted. Whereas some children may exhibit impairment in the ability to regulate incoming sensations, others may fail to detect and orient to novel or important sensory information, which is called sensory modulation disorder.5,6,12,62,68 Some types of sensory processing impairment may lead to poor social adaptation; the inability to form close, intimate relationships; and difficulty in expressing and interpreting socioemotional cues.44 Led by the pioneering work of Jean Ayres, occupational therapists have examined and developed treatment strategies for sensory integrative dysfunction in the early intervention and school-age populations since the early 1970s.2,4,5,8,10,12,33,42,59,62,58,71 The early signs of sensory processing problems can be observed even in infancy (Figure 24-1).63 Parents often report that they have noticed subtle differences—such as lack of cuddling behavior, failure to make eye contact, oversensitivity to sounds or touch, difficulty with the oral–motor demands of suckling, and chewing food—as early as in the perinatal period (Figure 24-2).45,70 Poor self-regulation of arousal states, irritability, and colic are frequently reported.1,46,67,70 In the toddler period, the motor, social, and self-care milestones may be delayed. The child may lack normal curiosity about the environment. On the other hand, he or she may explore the world in a disorganized and destructive manner, which does not lead to learning and mastery. Figuring out basic whole body movements, for example, climbing downstairs backwards or climbing onto a riding toy, are bewildering and frightening tasks.61,63 The preschooler with sensory-based motor planning problems may be unable to organize the body postures and gestures that are appropriate for nonverbal communication, such as the need for affection, to use the toilet, or for a favorite snack.63 Typically developing preschoolers can seem almost mesmerized with learning the process of dressing and will attempt the donning and doffing of clothes, shoes, and coats seemingly for hours at a time. However, the child with sensory-based motor planning deficits (called dyspraxia) may be dependent on caregivers for assistance and often avoids dressing and hygiene activities altogether. He or she may handle toys and objects ineptly, constantly damaging or breaking them. As the child attains school age, the heightened challenges of the elementary grades—sitting at a desk, paying attention in class, reading, listening, using writing and art tools, and interacting with peers—bring sensory processing dysfunction to light even more. During leisure time, the child may avoid fine manipulative activities or skilled gross motor play, instead preferring more sedentary activities such as watching television, playing video games, looking at books (Figure 24-3). Highly creative and intelligent children may conceal their motor control inadequacies by engaging in verbal make-believe play, which emphasizes imagination and social interaction (with a lot of aimless running around) over toy manipulation and body coordination. Occupational therapy (OT) practitioners need to consider observations such as the above behaviors within the context of the child’s family system, cultural expectations and norms, and socioeconomic advantages and limitations. As members of a team of professionals, they also utilize multiple sources of information from co-workers about the child’s cognitive, language, and social development because these areas of function will have significant effects on the quality of the child’s adaptive behavior.29 A child whose sociocultural and socioeconomic environments do not provide adequate opportunities for movement, exploration, and object play may need environmental enrichment to facilitate the emergence of motor planning skills. Initial OT evaluation typically employs a top-down approach, the first tier of focus being the child’s daily occupational and role performance.31,65 However, it may become apparent during the evaluation of occupational performance that sensory processing deficits are major contributors to the child’s functional difficulties, although the specific nature of the deficits cannot be delineated without further assessment. The OTA may be trained to physically administer a number of sensorimotor screening tests and other structured assessments of sensory processing and/or motor performance. However, the interpretation of the results should be performed by the occupational therapist, with the OTA providing important insights about the child. The OT practitioner will often collect this type of information on the children referred for OT because sensory processing dysfunction frequently contributes to the occupational performance difficulties for which children are referred, such as poor fine motor/handwriting skills, trouble with self-care tasks, social–emotional problems, or inability to participate in gross motor play activities with peers. A very important part of the assessment process includes getting initial data from observations of the child by his or her caregivers, teachers, and/or other therapists. If the existence of a sensorimotor processing issue cannot be ascertained, the OTA and his or her supervisor may then decide to administer a standardized screening test. Based on the results of those two sources, an experienced team of OT practitioners may have enough data to formulate an intervention plan. Otherwise, a decision may be made to pursue more comprehensive evaluation of the child’s capacities for sensory processing.22 A complete sensory processing evaluation typically covers five major areas: (1) sensory modulation across each sensory system (i.e., tactile, vestibular, visual, auditory, olfactory, and taste); (2) perceptual discrimination ability in most of these areas; (3) postural–ocular function; (4) bilateral motor coordination (including organization at and across the midline of the body); and (5) praxis (the ability to internally visualize and plan skilled or unfamiliar movement actions).6,18 However, the OT supervisor may elect to focus on fewer areas if the initial OT assessment and SI screening indicate that certain areas are not problematic. The hypothesis about the contribution of sensory processing dysfunction will help shape one aspect of the intervention approach, which will probably include activation of Jason’s proprioceptive system before handwriting activities. Therefore, when relating the SI assessment results to caregivers and other members of the team and in planning a course of intervention, the OT team must bring their interpretation of sensory processing issues full circle to explain their concern about the child’s occupational performance, which was the original source of the referral. Furthermore, either classroom or direct service interventions to address the underlying sensory processing issues will be recommended (Figure 24-4). Multiple observation checklists are available for use.24 Some can be found in pediatric OT textbooks, whereas others are available for purchase from test publishers. Some checklists are informal and based on SI problem behaviors cited in the clinical literature rather than on norms derived from children of various ages. They can be used to gain informative data from teachers as well as caregivers. Such tools can be helpful if used with the age range intended.19 Two examples of such tools are The Sensorimotor History Questionnaire and The Teacher Questionnaire of Sensory Behavior (see Appendices A and B at the end of this chapter).25, 27,28 Formal rating scales are based on knowledge of a child’s developmental history and direct observation and are administered by trained professionals who know the child’s behaviors, abilities, and preferences well. Such scales are often well researched and standardized on normative groups and fit into the class of SI screening instruments. A summary of them can be found in the literature, and some are described in Table 24-1.21 TABLE 24-1 The most comprehensive standardized test battery of sensory integrative functioning for children ages 4 years and 0 months through 8 years and 11 months is the Sensory Integration and Praxis Test (SIPT).3 These tests include measures of vestibular, proprioceptive, and somatosensory processing; visual perceptual and visuomotor integration; integration between the two sides of the body; and many of the components of the complex set of abilities known as praxis. The praxis tests include measures of postural imitation, motor planning in response to a verbal request, motor sequencing ability, imitation of oral movements, graphic reproduction, and three-dimensional block construction.2,3,11 One of the most challenging aspects of the interpretation of SI and praxis evaluation data is the lack of a concrete one-to-one correspondence between a low score on a particular test and the meaning of that score. Invariably, the SI assessment is about discovering the underlying sensory disorganization that leads to poor performance in one or more functional “end products.” In the typically developing child, these end products can come in the form of functional motor skills such as riding a bicycle or using tools, academic learning skills such as reading and computation, cognitive abilities such as language and abstract thinking, or psychosocial capacities such as emotional attachment and self-esteem. It is the end products of sensory integration which enable children to participate in age-appropriate occupational tasks and roles. However, between sensory organization and these end products there are also intermediate abilities termed functional support capacities by Kimball.47 Functional support capacities represent secondary neurobehavioral, motor, social–emotional, and cognitive proficiencies that are not functional in the occupational sense but are considered precursors for end products to develop normally. A number of these are measured by the SIPT and other tests and include components such as self-regulatory mechanisms, postural tone, bilateral motor coordination, ability to cross the midline of the body, various subtypes of praxis, cognitive sequencing, and other intermediate-level capacities. Therefore, numerous patterns of underlying dysfunction are possible; end product impairments are interpreted according to the way in which the SI and praxis test scores cluster. In summary, research using the SIPT as well as Ayres’s earlier tests has demonstrated that (1) various aspects of the components of sensory discrimination, bilateral motor organization, and motor planning tend to group together statistically to form predictable clusters; (2) developmental trends can be identified in most SI constructs; and (3) certain sensory systems integrate with one another to give rise to higher-order capacities in behavior and ability.3,5,7,9 With regard to the role of the additional neurobehavioral construct of sensory modulation, although Ayres originally identified the phenomenon of sensory registration disorders, which are now called sensory modulation disorders, she died before she was able to pursue a more objective method of measurement of these disorders. Fortunately, others have taken up this area of work.35,36,39,40,55,56,57,58,68,69 Research on psychophysiologic measurement has contributed significantly to our understanding in this area.36,38–40,49–51,54,55,57,58,69,70 This is only an imaginary taste of what life is like for people with sensory modulation dysfunction. However, some have sensory experiences that are so distorted that everyday sensations are uncomfortable, painful, frightening, or surreal in nature. A woman with agoraphobia and sensory modulation disorder reported to one of the authors that at times she would be walking on a concrete floor in a department store and suddenly feel as if the floor were soft and her feet were going through it, rather than striking the hard surface. At other times, she had trouble falling asleep because she felt as if bugs were crawling on her, or she was unable to habituate to the sound of a clock ticking in another room. Children commonly manifest sensory modulation irregularities by their intolerance of such stimuli as clothing, food textures, imposed touch, and household noises (e.g., a phone ringing or an appliance running) or, conversely, by not noticing salient stimuli in their environment. Probably the earliest harbinger of SI dysfunction in infancy is unusual over-reactivity to touch, taste, or smell. Some forms of gastric reflux in infancy appear to be precipitated not by gastroesophageal abnormalities but by olfactory hypersensitivity, which causes the infant to become nauseous.64 Examples of hyper- and hypo-reactivity can be identified as you look through The Sensory History Questionnaire (SHQ) shared previously. Research in which The Sensory Profile and The Adolescent and Adult Sensory Profile were used revealed that children and adults develop behavioral patterns of dealing with their modulation problems, which have been described by Dunn in her model of sensory processing.15,16,37,39 These patterns tend to divide into four quadrants that are bounded by (1) a continuum of sensory avoidance to sensory seeking, and (2) a continuum of acting in accordance with threshold, to acting to counteract threshold. We all fall within one of these quadrants, but dysfunction lies more at the extreme ends of the continua, where a person’s daily life and relationships are more apt to be disrupted by modulatory irregularities. These patterns of sensory modulation are also associated with various types of temperament, as identified by Thomas and Chess.32,66 For more information on this, the reader is referred to the work of Dunn, Miller, Wilbarger, and associates.35,37,52,58,59,60,62,70,71 Of the two broad patterns of sensory-based motor dysfunction, this one is milder in severity. It may be identified by a cluster of several sensory, behavioral, and motor characteristics, including irregularities in sensory modulation; atypical ocular pursuits, convergence, and visual fixation; low duration of postrotary nystagmus; slow or irregular vestibular response to tilt; sluggish postural preferences for inactive positions and sedentary activities; impairments in midline crossing, and delayed establishment of lateral dominance after age 4 (Figure 24-5).3,48,63

Sensory processing/integration and occupation

Screening and assessment of sensory processing

Observational and history-taking assessment

Formal assessment tools

NAME OF SCREENING TOOL

STATED PURPOSE

INTENDED AGE RANGE

Test of Sensory Function in Infants33

Designed to measure an infant’s sensory reactivity and processing to determine the presence and extent of the deficit

4–18 months

The Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile36

By means of the parents’ report, measures infant and toddler reactions to everyday sensory events across all modalities

Birth–36 months

The Sensory Profile35

Measures child’s responses to sensory experiences as well as perceived movement competence by means of the parents’ report

3–10 years

The Short Sensory Profile51

A one-page questionnaire with 38 items divided into 7 sections; answers based on a 5-point scale

3–10 years

The Adolescent/Adult Sensory Profile40

Self-report; measures responses of teens through mature adults to sensory events in everyday life

11–90 years

The First STEP Screening Test for the Evaluation of Preschoolers (Parent Checklists)52

General screening of major developmental areas, including several creative items of bilateral integration and praxis

2 years, 9 months–6 years, 2 months

The DeGangi-Berk Test of Sensory Integration34

A total of 36 items that measure overall sensory integration as well as postural control, bilateral motor integration, and reflex integration

3–5 years

The Miller Assessment for Preschoolers53

Broad overview of a child’s developmental status; several indices assessing key areas of sensory integration performance

2 years, 9 months–5 years, 8 months

Clinical Observations of Sensory Integration2

Clinical Observations Based on Sensory Integration Theory14

Informal floor assessment primarily assessing a child’s postural reactions and oculomotor responses that are included in most neurologic screenings of soft neurologic signs

Various ages; recommended for approx. ages 5–10 years

Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency17

Both short screening and long evaluation forms included; measures a variety of gross and fine motor skills; includes many items for assessing bilateral coordination

4.6–14.5 years

Comprehensive evaluation of sensory processing/integration

Sensory modulation disorder

Sensory-based movement disorder

Postural–ocular and bilateral integration dysfunction

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Sensory processing/integration and occupation

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue