16 Self-Perception Issues

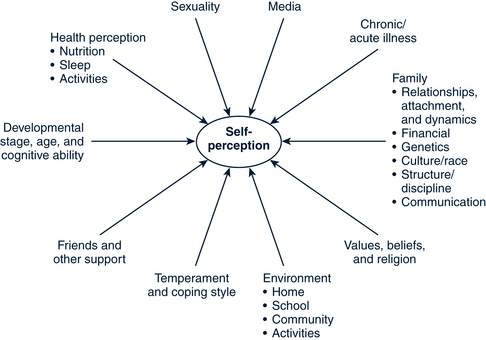

All people—children and adults—have mental pictures of themselves that steer the course of their lives. This mental picture, or self-perception, begins to develop at birth, emerges in childhood, and is refined and crystallized in adolescence, but it continues to evolve throughout life. Self-perception is often used as an indicator and even a predictor of mental health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010a; Wang and Veugelers, 2008; Wang et al, 2009). Multiple factors influence self-perception (Fig. 16-1). Self-perception has to do with how individuals act, think, and feel about themselves, their abilities, and their bodies. It is also influenced by the response of others to them. This perception, in turn, influences the attitudes each person takes and the choices each person makes throughout life. Children’s self-concept powerfully affects their happiness, academic performance, relationships, creativity, healthy risk-taking, perseverance, resilience, and problem-solving (Neifert, 2005). A positive self-perception is a precious gift that provides the confidence and energy to take on the world, to withstand crises, and to focus outside oneself. It enhances the building of relationships and giving to others. Adolescents (in particular) with a positive self-perception have a significant protective factor to minimize the risk of suicide (Sharaf et al, 2009). Positive self-esteem is protective because it enhances children’s abilities to deal with risk and learn to cope effectively (Riesch et al, 2006). People with a negative self-perception tend to focus on their own needs, trying to get and prove their self-worth. Children and adolescents with low self-perception have limited ability to respond to daily and developmental challenges (Wang and Veugelers, 2008). A negative self-perception drains energy, interferes with building relationships, and often leaves the person feeling like a victim. People with poor self-perception are more likely to participate in negative behaviors such as school absence, smoking, drinking, drug use, and delinquency, and are more likely to experience eating disorders, anxiety, depression, and suicidal behaviors (Slattery, 2008; Wang and Veugelers, 2008). Poor self-esteem can be a symptom of a mental health disorder or emotional disturbance (USDHHS, 2010a).

Standards of Care

Standards of Care

Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision (Hagen et al, 2008) does not specifically address self-perception, but interweaves it throughout the approach to health supervision. Bright Futures in Practice: Mental Health (Jellinek et al, 2002) focuses on prevention of psychosocial problems and early recognition of mental disorders. The comprehensive practice guide and toolkit have a section in each developmental chapter that focuses on self-functioning and its appropriate assessment and management. Both the Healthy People 2020 objectives (USDHHS, 2010b) and the Guide to Clinical Preventive Services (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF], 2010) address the need to screen for depression and potential suicide. Depression and suicide are potential complications of negative self-esteem and should be considered by the provider working with children and adolescents (see Chapter 19 for an in-depth discussion of these topics).

Normal Patterns of Self-Perception

Normal Patterns of Self-Perception

Components of Self-Perception

Self-perception, being personal and subjective, includes both a description of the self and an evaluation of that description. The description a person draws and the evaluation a person makes come from thoughts and feelings, beliefs and convictions, observations, understanding, insight, and awareness received both from the self and from others. The three key components of self-perception are significance, worthiness, and competence (Box 16-1). Significance comes from having a sense of belonging; feeling loved and lovable; feeling secure, cared for, and supported; and being accepted and understood unconditionally for whom one is, not what one does. This is the most important component in developing and maintaining a healthy self-esteem. Females are more likely to channel their self-perception into feeling desirable especially through relationships (Slattery, 2005).

BOX 16-1 Key Components of Self-Perception

Significance: “I am loved.” (Parent: “I love you, no matter what.”)

Worthiness: “I am OK. I like and respect myself.” (Parent: “I accept and respect you.”)

Competence: “I can do it.” (Parent: “I believe in you. You can do it.”)

Children who feel significant, worthy, and competent confidently initiate activities, explore the environment, take risks, and rebound from disappointments. Appreciating themselves, they are able to reach out to and interact with others, accepting and offering love, respect, and encouragement. Perry (2001) describes an active learning process beginning with a child’s natural curiosity that leads to mastery and accomplishment, thereby growing a child’s self-esteem and resilience (Box 16-2).

BOX 16-2 Enhancing Self-Perception: The Cycle of Learning

• Curiosity results in exploration.

• Exploration results in discovery.

• Discovery results in pleasure.

• Pleasure leads to repetition.

• Repetition results in mastery.

• Mastery results in new skills.

• New skills lead to confidence.

• Confidence contributes to self-esteem.

• Self-esteem increases sense of security.

From Perry BD: Creating novelty, Scholas Parent Child 9:67-68, 2001. Copyright © 2001 by Scholastic Inc.

Children who do not feel significant, worthy, and competent look increasingly to external measures, such as those listed in Box 16-3, to try to create a positive self-perception. Physical attractiveness, socioeconomic status, and intelligence (academic achievement) are three measures frequently used in society to evaluate people. State of physical health, temperament, coping style, and an overly protective environment are other factors that affect self-perception. However, undue or excessive emphasis on external measures causes children to compare themselves with others, adopting the description and evaluation others make of them. Most of us are what we think others think we are (Dobson, 1999), or “If you think you can’t, you can’t” (Neifert, 2005). Children whose self-perception is based on a comparison of themselves with others feel and describe themselves as insecure, inferior, and inadequate. Attempting to prove themselves, they often become both bossy and aggressive, or people pleasers and approval seekers. Red flags for self-perception are listed in Box 16-4.

BOX 16-3 External Measures Used to Build Self-Perception

Physical appearance or attractiveness: How do I look?

Importance: Whom do I know? Who knows me?

Financial status: What and how much do I have?

BOX 16-4 Red Flags for Self-Perception Problems

• Constantly asking for reassurance: Do I look OK? Am I fat?

• Constantly showing bravado: Do you know I know so and so? Do you know I’m involved with such and such?

• Depression or suicide: You are better off without me.

• Obsessive disorders, such as eating disorders, alcohol or drug use

Data from Slattery J: Self-esteem. In Discovery years, focus on your child, CD, 2005.

Developmental Stages

One theoretic perspective that can be useful clinically is to view the development of self-perception as occurring in two stages (Box 16-5). The first stage, emergence of the self, occurs in infants, toddlers, and preschool-age children. Parents and caretakers play a key role during this stage. Infants as early as 4 months old learn that they are separate individuals who affect others by their behavior, thus laying the foundation for self-development (Rochat and Striano, 2002). This is best accomplished in a supportive environment where infants come to view the world (their parents and caretakers) as responsive to their needs, both physical and emotional.

BOX 16-5 Developmental Stages of Self-Perception

Emergence of Self (First Stage)

• Infants—view the world as responsive or unresponsive to their needs and learn that they are separate individuals who affect others by their behavior.

• Toddlers—explore their capabilities and limits and make others aware of their needs, desires, and concerns.

• Preschoolers—begin to use personal pronouns and pretend play, become aware of discrepancies in abilities, discover their bodies, move from seeing themselves as the center of the world, describe themselves categorically.

Refining the Self (Second Stage)

• School-age children—become more confident of their own self-evaluation, evaluate self on the basis of external evidence, compare themselves with others, increasingly depend on peers for self-evaluation, criticize and ridicule deviations from normal.

• Early adolescents— “try-on” images, finalize body image, focus on physical and emotional changes with peer acceptance determining self-evaluation, use interpersonal self-description.

• Late adolescents—refine and crystallize self-perception (physical, social, spiritual) with values, goals, and competencies guiding their future in place.

Refining the self, the second stage of self-development, occurs in school-age children and adolescents as they developmentally become more self-aware. Friendships, peers, and the time spent in various activities play increasingly larger roles in shaping the child’s character and personality and thus self-perception. As early as 5 to 10 years old, children will cite themselves, not adults, as the authority on self-knowledge (Burton and Mitchell, 2003). Cultural stereotypes, such as those found in magazines, television, billboards, and the Internet, influence the child’s perception of society’s “ideal” self. School-age children are preoccupied with evaluating themselves on the basis of external evidence: cognitive and physical skills, achievements, physical appearance, social abilities and acceptance, and a sense of control. They are particularly prone to comparing themselves with others, making them more vulnerable to social pressure. Any deviation from what society considers “normal” is subject to criticism and ridicule.

Developmental Assets, Thriving, and “Sparks”

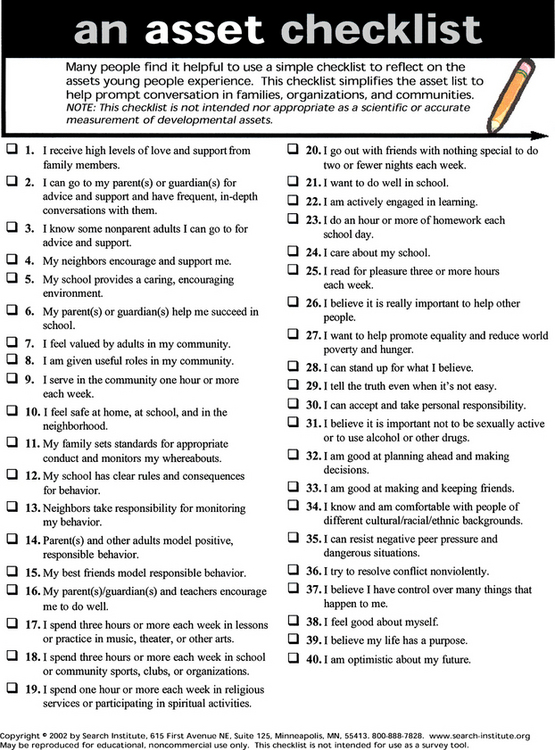

Developmental assets are positive experiences, relationships, opportunities, and personal qualities that are building blocks to help children and adolescents grow into healthy, caring, and responsible adults. In 1990, based on extensive research studies, the Search Institute identified 40 assets related to child and adolescent development, risk prevention, and resiliency (Search Institute, 2010a). The assets are found in eight areas of human development and are grouped into external and internal assets. External assets are factors in the environment (home, school, community) that (1) support, (2) nurture and empower, (3) set boundaries and expectations, and (4) speak to constructive use of time. Internal assets are attitudes that include: (1) a commitment to learning, (2) positive values, (3) social competencies, and (4) positive identity. The assets are described in the asset checklist (Fig. 16-2).

Building on the initial research done with adolescents, the Search Institute has now created Developmental Asset Lists for Adolescents (ages 12 to 18), Middle Childhood (ages 8 to 12), Grades K-3 (ages 5 to 9), and Early Childhood (ages 3 to 5). The asset lists have been translated into 14 different languages. All of these are accessible without charge at the Search Institute website (www.search-institute.org). Common threads and unique features for each developmental age group are reflected in the asset lists. The middle childhood assets include the transition toward emerging self-hood and self-regulation. The early-childhood assets respond to early childhood issues with essential ingredients that relate to school readiness, school success, and a happy productive life.

The latest research coming from the Search Institute has to do with the concepts of thriving and sparks (Search Institute, 2010c,d). Thriving “focuses on how an individual is ‘doing’ at any given point in time as well as the path that he or she is taking into the future.” Thriving indicators are “constructive behaviors, postures, and commitments that societies value and need in youth.” Sparks, as identified by Benson (2008), are “something inside your teenager that gets him excited. Sparks are the thing that gives teenagers (and actually all people) meaning.” Sparks are “an interest, talent, skill, asset, or dream that truly excites young people and helps them discover their true passions.” Using sparks help young people develop positive self-perception and discover and cultivate talents and interests that shape the rest of their lives. The 10 most common sparks identified by American teenagers are listed in Box 16-6.

Environmental Influences

Studies have shown that first-born children have higher levels of self-worth (Shebloski et al, 2005). As children get older, peers and authority figures also have an influence. Constant unconditional acceptance and love, empathy, and an attitude of understanding, coupled with appropriate limits and boundaries, are the most important interactions these significant others offer. Time spent with and encouragement given to the child, both in being together and in doing things, in addition to sharing life’s happenings (listening, talking, and problem-solving), are also essential ingredients (see the Parenting Pyramid discussed in Chapter 4). A key component in children’s development of positive self-perception is the sturdy base built by positive relationships. By feeling, seeing, and hearing these continual reinforcements, children internalize or know that they are significant, worthy, and competent.

Glascoe and Leew (2010) identified six positive parenting behaviors and perceptions that predicted average to above-average development in young children. Children with developmental assets that prepare them for school are less likely to have low self-esteem. Additionally, Glascoe and Leew (2010) identified four psychosocial risk factors. The parenting behaviors and risk factors are listed in Table 16-1. Riesch and colleagues (2006) reviewed individual, family, and environmental factors that predict poor self-esteem. Improving the parent-child communication process may reduce the risk of low self-esteem. In contrast, Neifert (2005) has identified six common errors that parents unintentionally make that chip away at their child’s self-esteem (Box 16-7). A study of French-Canadian children who experienced verbal aggression from parents (e.g., rejection, demeaning, terrorizing, criticizing, or insulting) showed significantly lower self-esteem. These children perceived themselves as less competent, less comfortable, less worthy, and more prone to depression (Solomon and Serres, 1999). In general, peers and authority figures serve to confirm or deny what is taught at home.

TABLE 16-1 Positive Parenting Behaviors and Psychosocial Risk Factors Affecting Child Development and Self-Perception

| Positive Parenting Behaviors and Perceptions | Psychosocial Risk Factors |

|---|---|

< div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|