7 Rheumatology

Musculoskeletal History

A meticulous rheumatologic history is the foundation of accurate diagnosis (Table 7-1). The exact location that the patient complains about should be given careful attention. Muscle, bone, and tendon or ligament insertion pain (enthesitis) may be interpreted as joint pain unless the clinician asks specifically for the parent or child to describe the symptoms. Often it is helpful for the clinician to ask the child to point with one finger to the site of maximal discomfort.

Table 7-1 Distinguishing Features of the Rheumatologic History

Physical Examination of the Musculoskeletal System

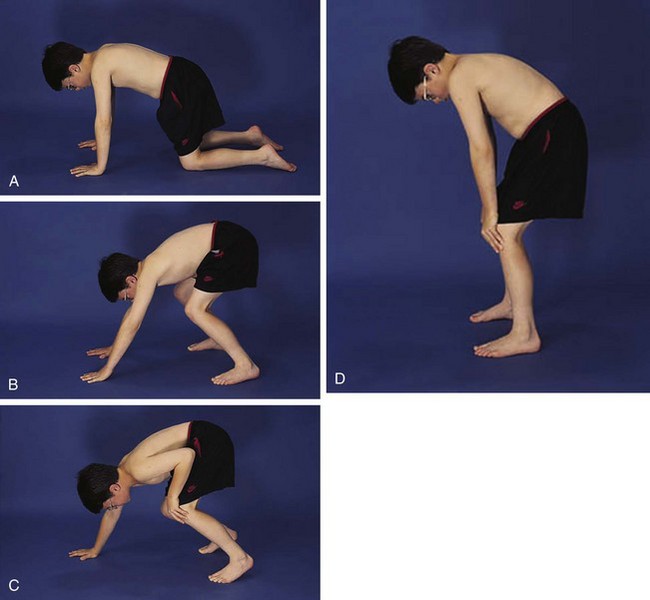

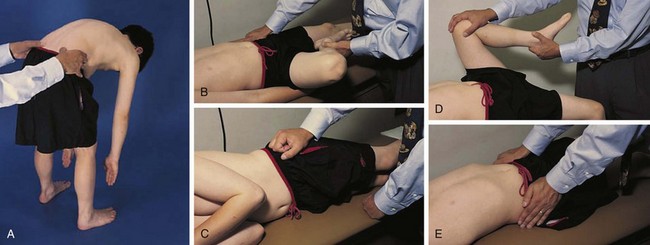

The physical examination begins with observation of the child and parents walking from the waiting area to the examination room. The physician notes the general appearance of the patient and interactions among family members. Nutritional status and an incremental graph of height and weight must be carefully documented. Certain skin and mucous membrane changes provide valuable information (Table 7-2). Muscle strength must be evaluated first by attempting to elicit a Gowers sign (Fig. 7-1) and then by testing resistance capacity of individual muscle groups and grading them on a standard scale (Table 7-3).

Table 7-2 Mucocutaneous Signs of the Rheumatic Diseases

MCP, metacarpophalangeal; PIP, proximal interphalangeal.

Table 7-3 Standard Muscle Strength Grading

| Muscle Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 5 | Complete range of motion against gravity with full resistance |

| 4 | Complete range of motion against gravity with some resistance |

| 3 | Complete range of motion against gravity |

| 2 | Complete range of motion with gravity eliminated |

| 1 | Evidence of slight contractility; no joint motion |

| 0 | No evidence of contractility |

Temporomandibular Joint

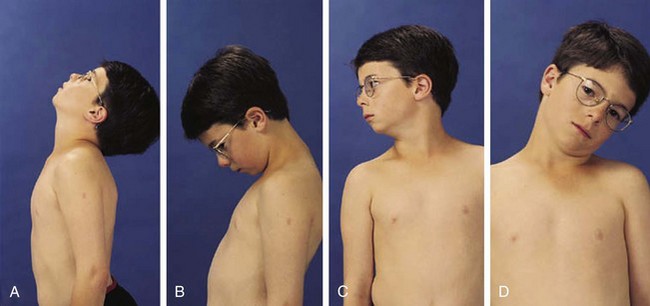

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) permits three types of motion: (1) opening and closing of the jaw, (2) anterior and posterior motion, and (3) lateral or side-to-side motion; each type should be carefully measured. Careful observation of the TMJ may reveal micrognathia, a clue to the diagnosis of JIA (Fig. 7-2).

Cervical Spine

In children the neck can be extended so that the head can touch the back and flexed so that the chin touches the chest; 90-degree rotation and 45-degree lateral bending in each direction is also normal (Fig. 7-3).

Shoulder

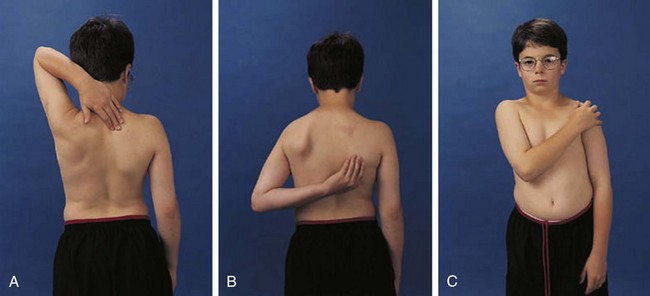

The shoulder is usually involved only in severe polyarticular JIA. It is an extremely complicated joint, but range of active motion can be conveniently tested by having the child perform three simple maneuvers (Fig. 7-4). These maneuvers require 180 degrees of abduction, 45 degrees of adduction, 90 degrees of flexion, and 45 degrees of external rotation of the glenohumeral joint and related articulations.

Elbow

The examiner must distinguish swelling in the olecranon bursa from involvement of the true elbow joint. The elbow is frequently affected in all forms of JIA and is the most common upper extremity joint affected in spondyloarthropathy. Range of motion of the elbow is easily tested (Figs. 7-5 and 7-6).

Wrist and Hand

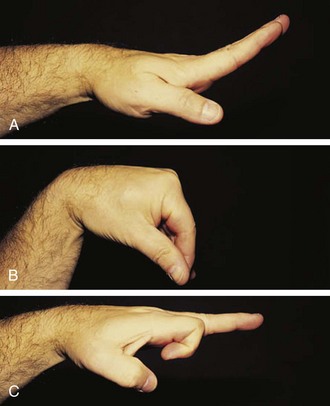

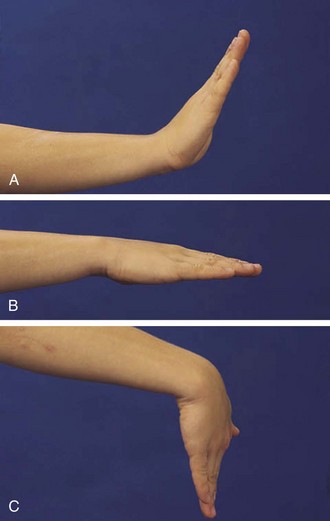

Children do not require much extension to perform most activities of daily living and thus can lose strength and mobility in the wrist, which may go unnoticed. The wrist is frequently affected in childhood arthritis, and thus a careful range of motion examination is essential. Normal is 70 degrees of extension, 80 degrees of flexion (Fig. 7-7), 20 degrees radially, and 30 degrees to the ulnar side.

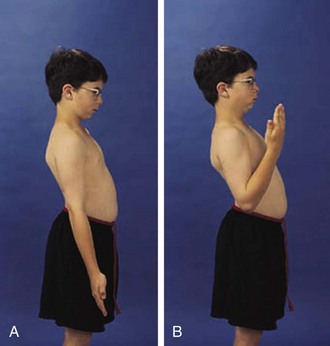

Figure 7-7 The wrist should extend to 70 degrees (A) from a neutral position (B) and flex to 80 degrees (C).

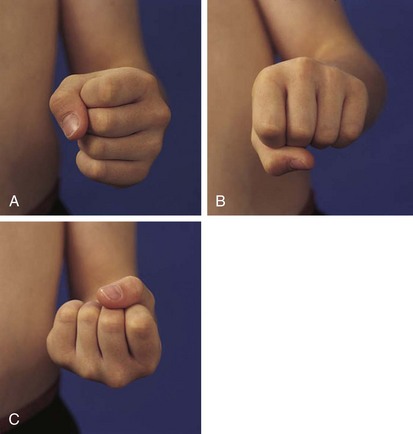

Metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints extend 30 degrees and flex 90 degrees. Normal range of motion for the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints is illustrated in Figure 7-8.

Hip

The normal hip examination consists of 45 degrees of abduction and 20 degrees of adduction (Fig. 7-9) with the knee bent 20 degrees. The hip can extend 30 degrees, externally rotate to 45 degrees, and internally rotate to 35 degrees. An increase in lumbar lordosis may be the first sign of decreased hip flexion. Normally, hip flexion reaches to about 135 degrees (Fig. 7-10).

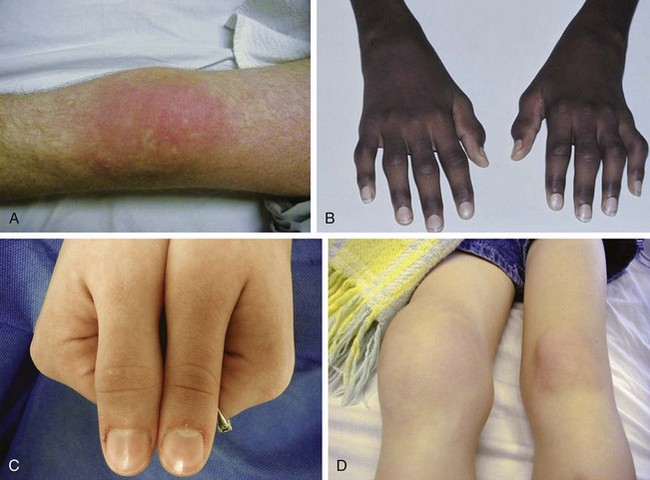

Knee

The knee is the joint most commonly involved in childhood arthritis. Swelling of the knee may be diffuse or localized to the suprapatellar bursa, which communicates with the true knee joint, or to the gastrocnemius-semimembranosus bursa (Baker cyst) (Fig. 7-11), which may dissect down the leg. The patella must be carefully evaluated for “roughening of the undersurface” indicative of chondromalacia patellae, which is not uncommon in teenage girls. Normal knee range of motion is illustrated in Figure 7-12.

Figure 7-11 Arthrogram demonstrates communication of Baker’s cyst with synovial cavity of the knee joint.

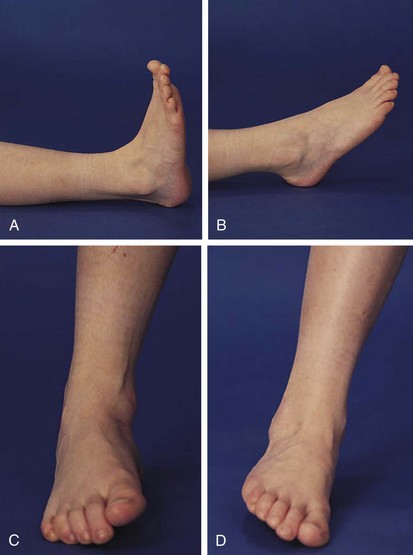

Foot and Ankle

The foot and ankle can offer valuable clues to the diagnosis of arthritis in childhood. Evidence of Achilles tendinitis or plantar fasciitis can suggest a spondyloarthropathy. First metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint involvement is also a strong clue to the diagnosis of a spondyloarthropathy. Normal ranges of motion of the true ankle joint and subtalar joint are illustrated in Figure 7-13, and decreased range of motion is common in oligoarticular JIA.

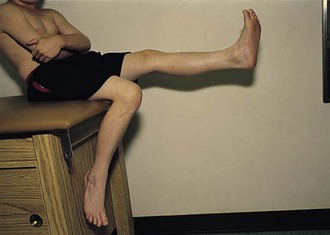

Leg Length

Leg length discrepancy (Fig. 7-14) is common in JIA because of hyperemia of an affected joint and subsequent overgrowth. Compensatory scoliosis may also develop.

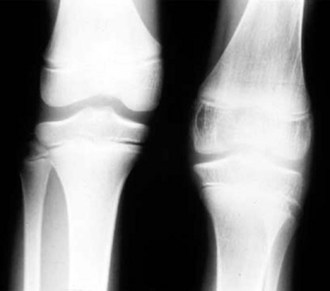

Thoracic Spine/Lumbar Spine/Sacroiliac Joints

The entire spine including all spinous processes should be carefully palpated to elicit tenderness. Flexion, extension, and lateral motion of the spine should be measured, using S1 as the focal point. Thirty degrees of extension and 50 degrees of lateral motion are normal. Careful examination of the sacroiliac joints (Fig. 7-15) may give an important clue to the diagnosis of a spondyloarthropathy in an adolescent. Chest expansion, occiput-to-wall, and finger-to-floor measurements (Fig. 7-16) are useful in monitoring patients with inflammatory back disease. To detect limitation of forward flexion of the lumbar spine, the Schober test is quite useful. The patient is asked to stand erect, and the skin overlying the spinous process of the fifth lumbar vertebra (usually at the level of the “dimples of Venus”) and another point 10 cm above in the midline are marked. The patient is asked to maximally bend the spine forward without bending the knees. If the lumbar spine is mobile, the distance between the two points increases by 5 cm or more; that is, the distance between the two points becomes equal to or greater than 15 cm. An increase of 4 cm or less indicates decreased mobility of the lumbar spine.

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

The first clear description of these entities was presented by George Still in 1897. He postulated multiple etiologies for childhood arthritis, and this concept is still supported today. All forms of JIA feature inflammation of the synovial tissue as one of the cardinal features. Synovium is usually hypertrophied, and joint effusions may occur. On physical examination (Fig. 7-17), joint swelling, loss of normal anatomical landmarks, tenderness, decreased joint mobility (Fig. 7-18), warmth, erythema, and joint deformity may be noted. It is typical for the child with JIA to have more joint stiffness than pain. Symptoms often develop gradually over a period of weeks or months before evaluation. Morning stiffness is often reported. The duration of morning stiffness correlates well with the degree of inflammation in children with JIA. Immobility and weather changes may exacerbate symptoms, although they have no impact on the underlying inflammatory component of the disease. Although arthralgia alone can be the initial presentation of JIA, the diagnosis cannot be confirmed without the presence of arthritis on physical examination.

Despite objective signs of arthritis, the patient with JIA may not experience pain. When inflammation persists for a long enough period of time, destruction of the articular surface and bony structures may occur (Fig. 7-19). Because of the poor regenerative properties of articular cartilage, these deformities are usually permanent. Fortunately, most cases of JIA are not associated with permanent joint deformity.

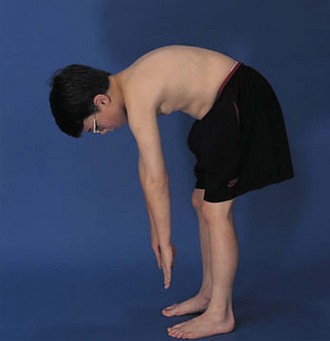

Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is diagnosed in a child with arthritis and psoriasis. Criteria are also met when a child with arthritis has two of the three findings: dactylitis (“sausage digit”), nail pitting (or onycholysis), or psoriasis in a first-degree relative. Whereas the forms of arthritis previously discussed have weak genetic penetrance, psoriasis and its related disorders are often found through a given family’s pedigree. A patient may often present to their physician with just dactylitis of one or multiple toes. In such a situation, in addition to a detailed joint examination, a detailed skin and nail examination should be performed (Fig. 7-20). Special attention should be paid to the scalp, the umbilicus, posterior ears, gluteal cleft, and shins.

Systemic Arthritis

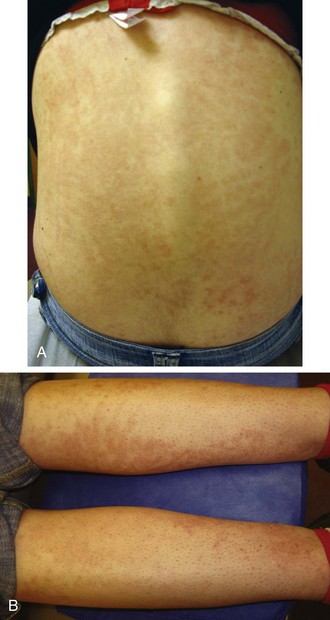

The rash of JIA is macular, 2 to 6 mm in diameter, evanescent, and salmon or red in color, with slightly irregular margins (Fig. 7-21). An area of central clearing often exists. The rash usually occurs on the trunk and proximal extremities, but it may also be distal in distribution, with palms and soles affected. Although the rash generally does not produce discomfort, some older patients report pruritus. Superficial mild trauma to the skin, exposure to warmth, and emotional upset may precipitate the rash (Koebner phenomenon). Arthritis may not occur invariably at the onset of systemic arthritis, and thus the diagnosis may not be readily apparent. When fever of unknown origin is the sole initial presentation of systemic arthritis, it must remain a diagnosis of exclusion until the clinician observes inflammatory arthritis during the physical examination. Arthralgia and myalgia can be prominent early, as can hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Serositis, pleuritis, pericarditis, hyperbilirubinemia, liver enzyme elevation, leukocytosis, and anemia are supporting clinical features. About 50% of patients with systemic arthritis progress to having chronic inflammatory arthritis, which often is destructive (Fig. 7-22).

Extraarticular Manifestations

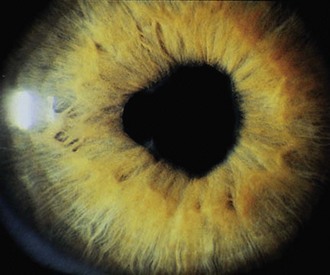

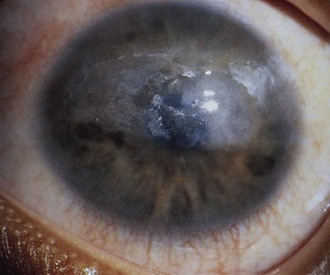

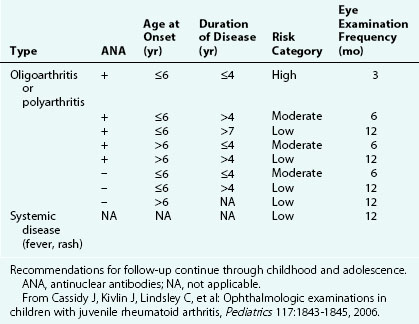

The first clinical sign of uveitis is cellular exudate in the anterior chamber. If the uveitis is left untreated, synechiae (adhesions) between the iris and lens may develop, leading to an irregular and poorly functioning pupil (Fig. 7-23). Further along in the clinical course, band keratopathy (calcium deposits in the cornea) (Fig. 7-24) may occur, as well as cataracts or glaucoma. For these reasons, strict adherence to the recommendations for eye examination outlined in Table 7-4 is necessary to help prevent visual loss in these children. Ophthalmologic complications do not parallel the activity of the arthritis.

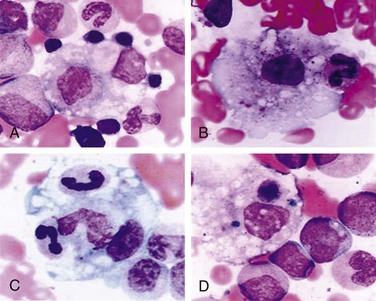

Patients with systemic arthritis are at risk for developing a potentially fatal disorder called macrophage activation syndrome (MAS). Patients present with a toxic appearance, fever, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and mucosal bleeding. If not recognized early, MAS can progress to hepatic failure, encephalopathy, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Laboratory testing that supports a diagnosis of MAS includes evidence of hepatitis and coagulopathy. In addition, the white blood cell count, hemoglobin, and platelet counts are depressed with a normal or low sedimentation rate (Table 7-5). Diagnosis is confirmed by bone marrow aspiration demonstrating activated macrophages engulfing surrounding cells (Fig. 7-25).

Table 7-5 Characteristics of Macrophage Activation Syndrome in Patients with Systemic-onset Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Modified from Cassidy JT, Petty RE: Textbook of pediatric rheumatology, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2005, WB Saunders.

Differential Diagnosis

Because JIA is a clinical diagnosis, strict clinical criteria have been established to make the diagnosis. Most authors suggest the presence of objective joint findings (arthritis) for a minimum of 6 consecutive weeks coupled with the exclusion of other causes of arthritis in children (Table 7-6).

Table 7-6 Differential Diagnosis of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

| Systemic Onset |

| Polyarticular Onset |

| Oligoarticular Onset |

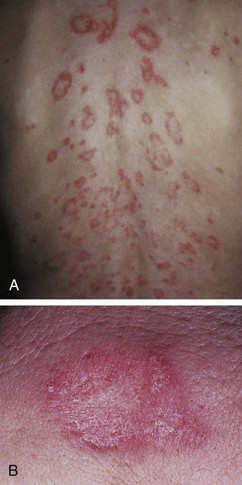

Lyme arthritis can mimic oligoarticular JIA. This spirochetal form of arthritis is tick-borne and usually affects the knee, elbow, or wrist in a monoarthritic pattern with spontaneous exacerbations and remissions. Malaise, fever, myalgia, lymphadenopathy, headache, meningismus, and weakness also may occur in the first phase of the illness. The distinctive rash, known as erythema migrans (Fig. 7-26), begins as an erythematous macule or papule. After this clears, the borders of the lesion expand to form an erythematous circular lesion that can be as large as 30 cm in diameter. These lesions can initially occur singly but can progress to multiple lesions over the legs, arms, and trunk. Other manifestations of Lyme disease include neurologic complications such as seventh nerve palsy, meningitis, radiculoneuritis, and the cardiac manifestations of heart block and myopericarditis. Bilateral Bell’s palsy or seventh nerve paralysis even more strongly suggests the diagnosis of Lyme disease.

Malignancies such as neuroblastoma and leukemia may present with musculoskeletal pain. More careful evaluation generally reveals bone pain. Sickle cell disease, particularly in the form of dactylitis, can have prominent digital involvement. Hemophilia, tuberculosis, and gonorrhea infection must be considered in the patient with arthritis. Differential diagnoses of JIA are proposed in Table 7-6.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystem auto-immune disease with a myriad of clinical presentations. SLE may present in an insidious fashion and hence escape early diagnosis, or it may present acutely and progress rapidly, leading to the patient’s demise. Frequently, children will present with nonspecific constitutional symptoms, such as fever, diffuse alopecia, weight loss, fatigue, and evidence of diffuse body inflammation with lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. All organ systems have the potential to become involved, but the most common are skin, musculoskeletal, and renal systems in pediatric SLE (pSLE). As with other collagen vascular diseases, the etiology of SLE is unknown. Because of the large number of serologic markers known to occur in SLE, it is considered by many to be the prototype of autoimmune diseases. To increase diagnostic accuracy, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) revised its classification criteria of lupus (Table 7-7). This classification, which combines clinical and serologic markers, is highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of this disease, reaching almost 100% sensitivity and specificity when 4 of the 11 criteria are present; however, the criteria are not meant for the clinical application of diagnosis and should be used as a study guide rather than applied to the clinical arena.

Table 7-7 Criteria for the Classification of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus*

* Four of 11 criteria provide a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 96%.

† Any one item satisfies this criterion.

Modified from Hochberg MC: Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus, Arthritis Rheum 40:1725, 1997.

The word lupus, which means wolf, alludes to the erosive nature of the rash of SLE (“wolf bite”) (Fig. 7-27). This feature of the disease was critical to the diagnosis of SLE until the discovery of the lupus erythematosus (LE) cell in 1948. The LE cell represents a healthy neutrophil that has phagocytosed the nuclear debris of a nonliving cell that has been coated with antibody. The antibody is directed against deoxyribonucleoprotein (DNP), which is made up of both DNA and histones. The presence of this serologic marker for lupus greatly expanded the recognized clinical entity of SLE. Although the LE preparation has proved to be of historical interest, time has shown that it is a nonspecific immunologic phenomenon and has no specificity with respect to the diagnosis of SLE; hence, although it was included in the ACR 1982 criteria, it was not included in the ACR 1997 criteria.

Cutaneous manifestations of SLE occur at some time during the course of the disease in 80% of affected individuals. There are a variety of cutaneous findings including a malar rash, photosensitive rash, palmar erythema (Fig. 7-28), annular erythema, vasculitic skin lesions with nodules or ulcerations, Raynaud phenomenon and associated ulceration, alopecia, and discoid lupus. Isolated discoid lupus is rarely seen in children, but when it occurs is usually without systemic manifestations. The same holds true for subacute cutaneous lupus, which is uncommon, presenting as a serpiginous-like photosensitive erythematous rash associated with positive SS-A (anti-Ro) antibody. The most frequent skin manifestations of SLE are malar rash and photosensitive rash. The classic malar or butterfly rash is a maculopapular rash distributed over the cheeks (malar eminences) and extending over the bridge of the nose, while sparing the nasolabial folds (see Fig. 7-27). The malar rash is photosensitive in 30% of the patients. In general, sun exposure may not only exacerbate the skin disease but also cause a systemic flare of disease, theoretically through large exposure of the immune system to intracellular proteins through massive apoptosis of damaged skin cells. Therefore, appropriate sun protection and avoidance is strongly encouraged. An annular photosensitive rash is frequently associated with the “Sjögren syndrome antibodies” anti-Ro (SS-A) and anti-La (SS-B). The typical morphology of the rash of lupus is defined as reddish purple and raised with a whitish scale (Fig. 7-29). When the scale is removed, the underlying skin often shows “carpet tack–like” fingers on the unexposed side of the scale itself. Carpet tacking is caused by the contouring of the scale into the skin follicles. These finger-like projections on a scale strongly suggest the diagnosis of lupus. Vasculitic rashes are more violaceous and may be associated with nodules, ulceration, and palpable purpura (Fig. 7-30). These lesions are commonly found in an acral distribution, and typically result in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Discoid lupus, although uncommon (5% to 10% of patients with pSLE), leaves the most damage with follicular plugging and scarring. Mucosal erosions and ulcers of the oral cavity and nasal mucosa are part of lupus as well, with the most well-recognized manifestation being the “silent” large violaceous ulceration of the hard palate (Fig. 7-31). Alopecia occurs in 20% of patients and may present as broken hair shafts or patchy, red, scaling areas on the scalp, which may eventually scar and cause permanent hair loss (Fig. 7-32). Other reported mucocutaneous findings are livedo reticularis (lacy, fishnet appearance of the skin), urticaria, atrophy, and telangiectasia. The presence of livedo reticularis may be the clinician’s only clue to an associated hypercoagulable state manifested by anti-phospholipid antibodies. This tendency can be diagnosed by obtaining a lupus anticoagulant panel, a functional assay that includes a partial thromboplastin time (PTT), anti-cardiolipin antibodies, and anti–β2-glycoprotein antibodies. Although anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) can occur as an entity alone, it is commonly associated with SLE. APS is defined as a hypercoagulable state characterized by both positive laboratory findings of anti-phospholipid antibodies and clinical findings of a variety of venous and arterial thromboses and recurrent fetal loss.

Figure 7-30 Systemic lupus erythematosus. Purpuric, ulcerative, and necrotic skin lesions of cutaneous vasculitis.

The heart is often significantly involved in patients with lupus. Although the pericardium is involved most commonly, the myocardium and the endocardium may also be of clinical importance. Pericarditis with associated pericardial effusion can be painless and may present only as cardiomegaly on a chest radiograph (Fig. 7-33) or as pericardial effusion on an echocardiogram. However, chest pain may be noted, especially on deep inspiration and when lying down. Auscultation of a friction rub signifies pericarditis. Although pericarditis is usually mild, it can progress to life-threatening cardiac tamponade. If the myocardium is affected, life-threatening complications including dysrhythmias, heart failure, and infarction can result. Libman-Sacks endocarditis is the term given to the verrucous projections of fibrinoid necrosis in the endocardium. These lesions rarely cause clinical symptoms, although the presence of a murmur raises suspicion of endocardial disease. The mitral valve is most commonly involved, although aortic and tricuspid valves may be similarly affected. The presence of Libman-Sacks endocarditis should also alert the clinician to the possibility of an underlying anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome. The major cardiac morbidity associated with SLE, which is gaining more recognition in the adolescent pediatric SLE population, is premature atherosclerosis. Several factors contribute to the risk of atherosclerosis, including chronic inflammatory processes, altered endothelial function, lipid abnormalities, nephritis, and proteinuria. Monitoring and controlling classic Framingham risk factors in addition to factors attributable to lupus are critical for long-term morbidity.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree