Chapter 70 Rheumatologic Diseases

JUVENILE RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

EVALUATION

What Is the Typical Clinical Presentation of Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis?

1 Pauciarticular: Involves fewer than 5 joints, with large joints such as the knee usually the most affected. Rarely, the hip is the presenting joint. Young girls are most commonly affected. Ophthalmologic examination is necessary to identify uveitis, which occurs commonly but may be clinically silent until irreversible damage occurs. Frequent follow-up is needed to prevent permanent vision loss.

2 Polyarticular: Involves more than 5 joints, most often in the wrists and hands. This form is more common in older girls. Rheumatoid nodules and erosive joint damage develop often.

3 Systemic onset: This form of JRA usually presents with high fever (> 39° C) for several weeks in children who appear systemically ill. Anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, pericarditis or pleural effusions (serositis), and a salmon-colored rash commonly accompany the fever. The rash may come and go with fever. Arthritis may be either pauciarticular or polyarticular; it may not be present initially but becomes the prominent finding as the systemic symptoms resolve.

What Laboratory Tests Should I Order?

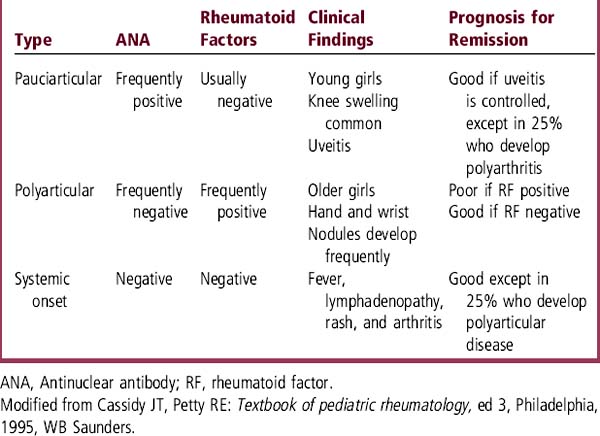

Complete blood count (CBC) may reveal anemia of chronic disease or iron-deficiency anemia from gastrointestinal blood loss caused by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is often elevated. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) and the rheumatoid factor (RF) may be variably positive, as indicated in Table 70-1. Patients on NSAIDs are monitored for liver toxicity by checking liver enzymes and for renal dysfunction by periodically checking a urinalysis.

SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

EVALUATION

How Do Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Present?

Most of the physical findings in SLE result from vasculitis. SLE can present at any age from the newborn period into adult life. The typical patient with SLE is an African-American adolescent girl with weight loss, fatigue, arthralgias, and rash, all of which often are induced by sun exposure. Over the course of the illness, 80% develop glomerulonephritis. Neonatal lupus manifests as rash and heart block in a newborn infant, resulting from placental transfer of autoantibodies from a mother with the disease. Outside of the neonatal period, SLE is uncommon in males and in children younger than 10 years. SLE should be considered in the differential diagnosis when children or adolescents present acutely with unusual findings, such as thrombosis, psychosis, or pericardial or pleural effusions (serositis). Table 70-2 depicts the most common multiorgan system findings in SLE. Diagnosis is based on the combination of clinical findings plus laboratory test results. To categorize patients as having SLE for clinical research studies, 4 of the 11 findings in Table 70-2 must be present. In clinical practice, the diagnosis is often made with fewer than four findings.

Table 70-2 1982 Revised Criteria for Diagnosis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

| Skin/mucous membrane |

| Malar rash: Red, “butterfly” flat or raised rash over malar eminences, tending to spare the nasolabial folds |

| Discoid rash: Red plaques with scales potentially leading to atrophic scarring |

| Photosensitivity: Appearance or worsening of a rash with sun exposure |

| Oral: Painless oral or nasopharyngeal ulcers |

| Arthritis |

| Nonerosive arthritis involving two or more peripheral joints, with tenderness and swelling |

| Serositis |

| Pleuritis—evidence of a pleural effusion, or |

| Pericarditis—documented exam, ECG, or echocardiogram findings of pericardial effusion |

| Renal disorder |

| Persistent proteinuria > 0.5 g/day, or |

| Cellular casts—may be RBC, granular, tubular, or mixed |

| Neurologic disorder |

| Seizures—in the absence of offending drugs or metabolic abnormalities, or |

| Psychosis—in the absence of offending drugs or known metabolic abnormalities |

| Hematologic disorder |

| Hemolytic anemia (frequently Coombs’ positive) |

| WBC: Leukopenia (< 4000/mm3 × 2) |

| Lymphopenia (< 1500/mm3 × 2) |

| Platelets: Thrombocytopenia (< 100,000/mm3) |

| Immunologic disorder |

| Positive LE cell preparation, or |

| Anti-DNA antibody to native DNA in abnormal titer, or |

| Anti-Sm—presence of antibody to Sm nuclear antigen, or |

| False-positive serologic test result for syphilis for at least 6 months |

| Antinuclear antibody (ANA) |

| Abnormal ANA titer in absence of drugs known to cause false-positive results |

ANA, Antinuclear antibody; ECG, electrocardiogram; LE, lupus erythematosus; RBC, red blood cell; Sm, Smith antigen; WBC, white blood cell.

From Tan EM et al: The 1982 revised criteria for the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus, Arthritis Rheum 25:1271, 1982, with permission.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree