1 Resuscitation

Clinical Presentation

The signs and symptoms of children requiring immediate resuscitation are typically the result of failure of the delivery of two vital substrates—oxygen and glucose—to end organs (Table 1-1). Recognition of these manifestations through a physical examination that focuses on airway, gas exchange, and cardiovascular stability allows for rapid resuscitation of those who have failure of substrate delivery and identification of those at risk for failure.

Table 1-1 Signs of a Life-Threatening Condition

| Airway | Complete or severe airway obstruction |

| Breathing | Apnea, significant work of breathing, bradypnea |

| Circulation | Absence of detectable pulses, poor perfusion, hypotension, bradycardia |

| Disability | Unresponsiveness, depressed consciousness |

| Exposure | Significant hypothermia, significant bleeding, petechiae or purpura consistent with septic shock, abdominal distension consistent with acute abdomen |

Adapted from American Academy of Pediatrics and American Heart Association: Pediatric Advanced Life Support. Dallas, TX, American Heart Association Publication, 2006.

Initial Assessment

Primary Assessement

Airway

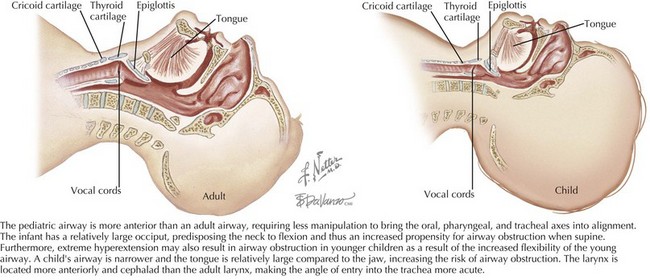

The patient’s airway is the first priority. There are fundamental differences between the airway of a child and that of an adult. The pediatric airway (Figure 1-1) is more anterior than the adult airway, requiring less manipulation to bring the oral, pharyngeal, and tracheal axes into alignment. In addition, the head-to-body proportion is larger in infants than in adults, and thus extreme hyperextension of the neck may exacerbate airway obstruction in younger children. The pediatric airway is narrower, and the tongue is relatively large compared with the jaw, increasing the risk of airway obstruction. The pediatric larynx is located more anteriorly and cephalad than the adult larynx.

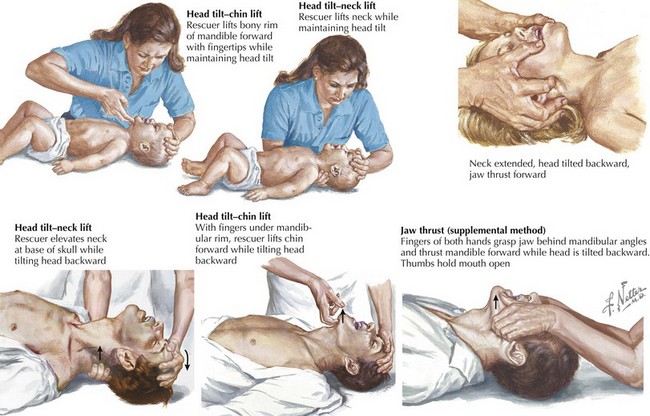

The most effective maneuvers for opening an obstructed pediatric airway are the head tilt–chin lift or jaw thrust techniques (Figure 1-2). In the head tilt–chin lift maneuver, the head is tilted back slightly (without overextending), and the chin is lifted gently with one finger on the bony prominence to avoid placing pressure on the soft tissues of the neck. A roll or towel may be placed under the shoulders to maintain the position.

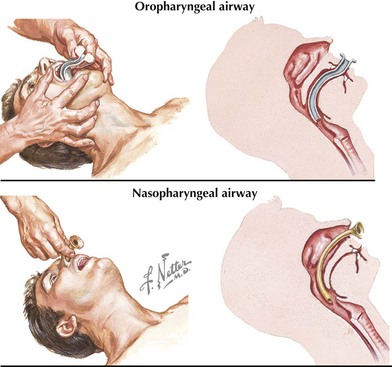

In an unconscious patient, an oropharyngeal airway can be used to help stent the mandibular block of tissue away from the posterior hypopharynx (Figure 1-3). A nasopharyngeal (NP) airway is another option. NP airways are well tolerated in unconscious and semiconscious patients and may even be used in conscious individuals with upper airway obstruction. NP airways should be used with caution when midface trauma is suspected because of the risk of inserting the airway through fractured bone into intracranial structures. Laryngeal mask airways (LMAs) are supraglottic airway devices that are being increasingly used in resuscitation settings to help bypass the soft tissues of the anterior oropharynx and to deliver oxygen directly to the proximal trachea.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree