19

Respiratory medicine

Chapter map

Respiratory infections and asthma are major causes of morbidity and are common reasons for a child being taken to a doctor or admitted to hospital. Certain problems are more common at certain ages, and the same organism may cause different illnesses at different ages (e.g. respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) causes bronchiolitis in infants, and a cold or a sore throat in older children). Cystic fibrosis is one of the commonest life threatening genetically inherited conditions in the Caucasian population. Early recognition and careful paediatric management greatly improves outcome.

19.1 Symptoms of respiratory tract disease

19.2.1 Recurrent coughs and colds

19.7.2 Assessing severity of asthma (Table 19.3)

19.8.1 Clinical features and presentation

19.8.3 Treatment and prognosis

19.1 Symptoms of respiratory tract disease

Cough in children is usually an upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) and less often lung disease. A barking cough suggests a laryngeal or tracheal disorder, usually croup (see Table 19.1). Young asthmatics may cough instead of wheeze, especially at night. Children usually swallow their sputum unless it is copious. Purulent and blood-stained sputum are rare. Ear ache (manifested by pulling at the ear in young children) suggests acute otitis media, although remember that pain from lower back teeth may be referred to the ear.

Table 19.1 Respiratory symptoms and their causes

| Symptom | Causes | Character |

| Cough | Croup | Barking |

| URTI | Throaty | |

| Asthma | Worse at night | |

| Pneumonia | Productive of phlegm (but children usually swallow this) | |

| Bronchiolitis | RSV cough unpleasant with characteristic ‘wet’ sound | |

| Pertussis | Paroyxysms of coughing, ending with inspiratory ‘whoop’, persists many days | |

| Shortness of breath | Asthma | |

| Pneumonia | ||

| Bronchiolitis | ||

| Noisy breathing Stridor (a monophonic noise arising from the upper airway, usually inspiratory) | Croup Foreign body Epiglottitis | Accompanied by barking cough History of inhalation or choking? Muffled cough, drooling, high temperature Rare since Hib vaccine If suspected, don’t examine throat |

| Wheeze (a polyphonic | Asthma | Widespread |

| musical noise arising | Pneumonia | Focal |

| from the bronchi/ | Inhaled foreign body | Focal |

| bronchioles, usually more expiratory than inspiratory) | Bronchiolitis | Widespread, with inspiratory crackles in under-2s |

| Snuffles/nasal obstruction | URTI | |

| Ruttles/rattles | Mucus ‘rattling’ in large airways |

Respiratory distress and failure

Respiratory distress and failure- Tachypnoea (>50/min infants; >40/min in children)

- Intercostal/subcostal recession

- Use of accessory muscles (arms and shoulders)

- Expiratory grunting, nasal flaring and ‘head-bobbing’ in infants

- Severe respiratory distress or

- Diminished respiratory effort, apnoea

- CNS signs of hypoxia: agitation; fatigue; drowsiness

- Cyanosis

- Collapse.

19.2 Upper respiratory tract

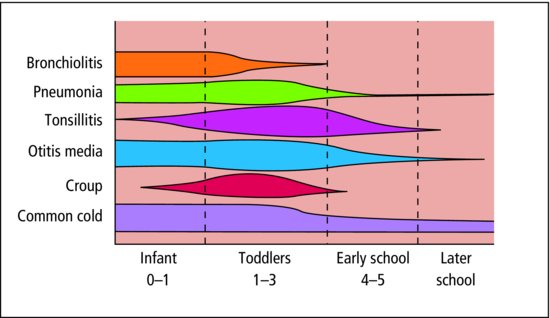

Most illnesses of childhood are infections; most childhood infections are respiratory; most are URTI (Table 19.2). The incidence and type of respiratory infections varies with age (Figure 19.1).

Table 19.2 Upper respiratory tract infection (URTI)

| Infection | Description | Causes |

| All may cause fever, vomiting and anorexia | The great majority are viral | |

| Common cold | Cough, rhinitis, sneeze | Viral |

| Tonsillitis | Enlarged, inflamed tonsils, +/- exudate | Viral or bacterial |

| Pharyngitis | Inflamed throat | Viral or bacterial |

| Acute otitis media | Ear ache, inflamed and bulging tympanic membrane | Viral or bacterial |

PRACTICE POINT

PRACTICE POINTIn the infant, nasal obstruction due to the common cold may lead to feeding difficulties. Saline drops and gentle suction can remove obstructing mucus plugs from the nostrils, but decongestant drops should be avoided. Eustachian tube obstruction often causes ear ache and the eardrums may appear congested. Antibiotics are not indicated. Paracetamol will reduce fever and relieve discomfort.

URTI may precipitate febrile convulsions (Section 17.1.1) and asthma attacks, and is sometimes the precursor of acute specific fevers, especially measles (Table 14.3) or bronchiolitis.

19.2.1 Recurrent coughs and colds

Recurrent coughs and colds, sometimes with sore throat and ear ache, are very common in young children, particularly if they have older school-age siblings, or mix with other children in a nursery. Some babies and toddlers are catarrhal much of the time. The first winter at school or nursery is frequently punctuated by upper respiratory infections.

- Postinfective

- Run of recurrent URTIs

- Postnasal drip

- Asthma (exercise, night)

- Cigarette smoke

- Habit

- Pertussis

- Foreign body

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux

- Cystic fibrosis

- Tuberculosis

- Immune deficiency.

Poor social circumstances and passive smoking predispose to catarrh. Some children will not blow their noses; some with severe nasal obstruction cannot. Aromatic inhalations and rubs can be useful in older children, but should be avoided in young infants, particularly under 3 months. Decongestants and cough suppressants are not recommended. The best healer is the passage of time.

19.3 Apnoea

Temporary cessation of breathing is a frightening occurrence. It can result from central respiratory depression or from mechanical obstruction (including the inhalation of food or vomit). It may occur during the first day or two of respiratory infections, particularly pertussis or RSV. However, many infants are rushed to hospital by their parents, who believe their child has stopped breathing. Often it is not clear whether anxious parents have merely misinterpreted the normal variable breathing of a small baby, or whether the baby genuinely has had a significant spell of apnoea. When the apnoea is associated with cyanosis, or unconsciousness, the differential diagnosis must include a seizure, congenital heart disease or airways obstruction. For very worried parents, the loan of an apnoea alarm, which sounds when the baby stops breathing, may be comforting. There is no evidence that apnoea alarms prevent sudden infant death syndrome (Section 15.3). Most children who die suddenly and unexpectedly in early life have not had previous spells of apnoea.

19.4 Influenza

Influenza tends to occur in epidemics, affecting particularly school children and young adults. The general symptoms of high fever, headache and malaise tend to overshadow the dry cough and sore throat, though there may be signs of pharyngitis, tracheitis or bronchitis. The main complications result from secondary bacterial infection of lungs, middle ear or sinuses. The brief incubation period and high infectivity favour massive outbreaks. Immunization against more common strains is given to children at risk of severe infection. Treatment is usually symptomatic. Antiviral agents may be considered in severe disease, or in at-risk children (e.g. chronic respiratory disease) presenting with milder illness during epidemics.

19.5 Lower respiratory tract

The bronchial tree and its blood supply are present by the 20th week of gestation, and thereafter only enlarge. In contrast, the alveoli increase in number from 20 million at birth to the adult complement of 300 million. Respiratory disease in early childhood may therefore interfere with future lung development as well as cause direct lung damage. Small airways obstruct or collapse early, leading to poor oxygenation or collapse of a lung segment.

19.5.1 Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis occurs at all ages and is characterized by cough, fever and often wheezing. It is a common feature of influenza and whooping cough. Persistent bacterial bronchitis is an occasional cause of chronic cough in children and may be confused with asthma. A cough swab may aid diagnosis, and a prolonged course of antibiotics (2 weeks or longer) is usually effective.

19.5.2 Bronchiolitis

Bronchiolitis is the most common cause of severe respiratory infection in infancy; 70% is due to RSV, 90% of children are immune to this virus by 2 years of age. Most children remain at home with this infection, but 1–2% of all infants are admitted each year, usually during the winter epidemics.

Younger infants and those with marked respiratory distress are more likely to need hospital admission. Supportive management includes skilled nursing, intravenous fluids, nasogastric feeding and oxygen, usually monitored with pulse oximetry. Nasogastric feeding is needed frequently to maintain fluid and calorie intake. Antibiotics are usually not indicated unless there is evidence of bacterial infection or severe disease. The RSV may be detected by fluorescent antibody test on nasopharyngeal secretions. Most infants recover within a few days. Up to half of infants with RSV bronchiolitis subsequently develop recurrent wheezing.

19.5.3 Pneumonia

19.5.3.1 Bronchopneumonia

This is most common in young children and in older children with a chronic condition affecting respiratory function (e.g. cystic fibrosis, severe cerebral palsy). A wide variety of organisms can be responsible. It commonly follows bronchiolitis, viral infection and whooping cough. Clinical features include rapid breathing, dry cough, fever and fretfulness. Generalized crepitations and rhonchi are usually present. Cyanosis occurs in severe cases and infants may develop cardiac failure. Chest X-ray often shows small patches of consolidation. Hospitalization is usually needed. Oxygen and a broad-spectrum antibiotic are given. Gentle physiotherapy helps to mobilize secretions. Infants may need tube feeding.

19.5.3.2 Lobar pneumonia

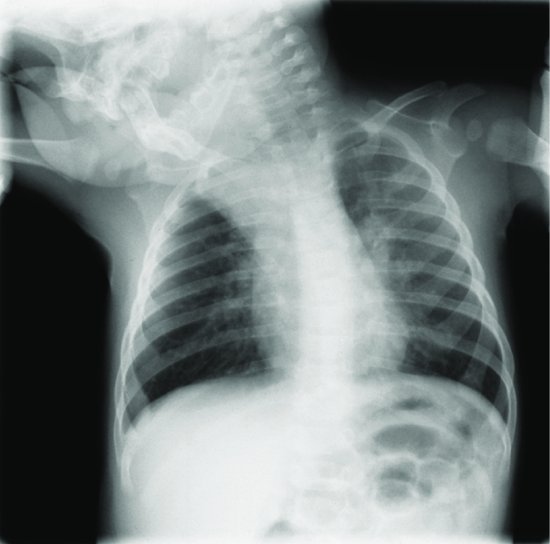

Pneumonia presents with sudden illness and high fever. The child is sick, looks flushed, breathes fast and has respiratory distress (Section 3.5.3). There may be no cough. Pleuritic pain may cause the child to lean towards the affected side, or may be referred to the abdomen or neck. The clinical signs of consolidation may not be present at first, but repeated examination will usually reveal them. A transient pleural rub is common. Lobar consolidation, with or without pleural effusion, is usually evident on X-ray (Figure 19.2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree