31 Respiratory Disorders

Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomy and Physiology

Upper Respiratory Tract

• Maxillary and ethmoid sinuses as early as late infancy

• Sphenoid sinuses around the third and fourth years of life

The trachea and airways of the infant and young child are more compliant than those of an adult. Hyperextension of the neck can constrict the airway of infants. Consequently, changes in intrapleural pressure lead to greater changes in an infant’s or young child’s airways compared with the effect that such changes would exert on adult airways, thereby causing an increased risk of airway collapse. Similarly, increased chest wall compliance in young infants makes them more vulnerable to adverse events, and their respiratory muscles cannot effectively handle sustained, intense respiratory workload that occurs during severe pulmonary illnesses (Sarnaik and Heidemann, 2007).

Pathophysiology Involved in Airway Disease

Pathophysiology Involved in Airway Disease

• Presence of intraluminal material (e.g., secretions, tumors, or foreign matter)

• Mural thickening (e.g., edema or hypertrophy of the glands or mucosa)

• Contraction of smooth muscle (e.g., spasm)

The primary clinical manifestation of lower airway obstruction occurs during expiration. Wheezing is the principal sound patients make if the obstruction allows enough air to pass through the narrowed lumen. Chest excursion diminishes, and the expiratory phase prolongs. Increased airway resistance during exhalation results in overinflation of the lungs, which in turn eventually increases the anteroposterior diameter of the chest. Chronic overinflation results in the “barrel chest” typical of a patient with chronic lung disease such as cystic fibrosis (CF) or emphysema. The accumulation of fluids and inflammation in the lower airways usually results in a repetitive hacking, ineffectual cough. On physical examination, percussing an overinflated chest elicits hyperresonance.

Defense Systems

Defense Systems

• Warming and humidifying of inspired air

• Clearing of airway through mucociliary and coughing actions

Biologic processes that protect the respiratory system include:

Assessment of the Respiratory System

Assessment of the Respiratory System

The history provides valuable information about the causes, progression, and potential complications of a child’s respiratory condition. The physical examination and diagnostic testing allow the provider to determine the extent of respiratory distress.

History

• History of the present illness can be assessed using the mnemonic PQRST:

Note any infections, constitutional diseases, or congenital problems that might have a respiratory component.

Note any infections, constitutional diseases, or congenital problems that might have a respiratory component.TABLE 31-1 Key Characteristics of Cough, Common Causes, and Questions to Ask in a Pediatric History

| Key Characteristics to Consider and Questions to Ask | |

|---|---|

| Age factor | Infants have a weak, nonproductive cough. |

| Quality | Staccato-like (Chlamydia trachomatis in infants); barking or brassy (croup, tracheomalacia, habit cough); paroxysmal or inspiratory whoop (pertussis or parapertussis); honking (psychogenic). Is the cough wet or dry? |

| Duration | Acute (most causes are infectious and last less than 2 weeks), subacute cough lasts from 2-4 weeks; recurrent (associated with allergies and asthma), or chronic lasting greater than 4-8 weeks (e.g., CF, asthma). Is the cough continuous or intermittent? |

| Productivity | Mucus producing or nonproductive? |

| Timing | During the day, night (associated with asthma), or both? |

| Effect on parent and child | Are parents frustrated with the cough? Is it causing them to lose sleep and work time? Are they concerned that the child may have something serious? |

| Associated symptoms | Fever—may indicate bacterial infection (pneumonia) |

| Rhinorrhea, sneezing, wheezing, atopic dermatitis—associated with asthma and allergic rhinitis | |

| Malaise, sneezing, watery nasal discharge, mild sore throat, no or low fever, not ill appearing—typical of URI | |

| Tachypnea—pneumonia or bronchiolitis in infants (infants may not have a cough) | |

| Exposure to infection or travel | Has the child been out of the country (tuberculosis)? Is there a member of the household being treated for “bronchitis” or another cough illness? |

| Causes | |

| Congenital anomalies | Tracheoesophageal fistula, vascular ring, laryngeal cleft, vocal cord paralysis, pulmonary malformations, tracheobronchomalacia, congenital heart disease |

| Infectious agent | Viral (RSV, adenovirus, parainfluenza, HIV, metapneumovirus, human bocavirus), bacterial (tuberculosis, pertussis, Streptococcus pneumoniae), fungal, and atypical bacteria (Chlamydia and Mycoplasma) |

| Allergic condition | Allergic rhinitis, asthma |

| Other | FB aspiration, gastroesophageal reflux, psychogenic cough, environmental triggers (air pollution, tobacco smoke, wood smoke, glue sniffing, volatile chemicals), CF, drug induced, tumor, congestive heart failure |

CF, Cystic fibrosis; FB, foreign body; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; URI, upper respiratory infection.

Adapted from Chang AB: Cough, Pediatr Clin North Am 56:19-31, 2009; Cherry JD: Croup (laryngitis, laryngotracheitis, spasmodic croup, laryngotracheobronchitis, bacterial tracheitis, and laryngotracheobronchopneumonitis. In Cherry J, Demmler-Harrison G, Kaplan S et al, editors:. Feigin & Cherry’s textbook of pediatric infectious diseases, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders, pp 254-268.

Physical Examination

• Measurement of vital signs and observation of general appearance:

A normal respiratory rate is age dependent and, if elevated, is a key indicator of lower respiratory involvement.

A normal respiratory rate is age dependent and, if elevated, is a key indicator of lower respiratory involvement. The level of anxiety, nasal flaring, and position of comfort are useful indicators of respiratory distress. Changes in skin color may be subtle or obvious depending on the level of deoxygenation. Grunting is a sign of small airway disease.

The level of anxiety, nasal flaring, and position of comfort are useful indicators of respiratory distress. Changes in skin color may be subtle or obvious depending on the level of deoxygenation. Grunting is a sign of small airway disease. Nose: Look for rhinorrhea—clear, mucoid, mucopurulent; FBs, erosion, polyps, lesions, bleeding; septal position; and color of the mucous membrane.

Nose: Look for rhinorrhea—clear, mucoid, mucopurulent; FBs, erosion, polyps, lesions, bleeding; septal position; and color of the mucous membrane. Throat, pharynx, and tonsils: Look for lesions, vesicles, exudate, enlargement of any structure, or other abnormalities. If epiglottitis is a consideration, do not inspect the mouth or attempt to elicit a gag reflex.

Throat, pharynx, and tonsils: Look for lesions, vesicles, exudate, enlargement of any structure, or other abnormalities. If epiglottitis is a consideration, do not inspect the mouth or attempt to elicit a gag reflex. Chest: Look at the depth, ease, symmetry, and rhythm of respiration. These are key indicators of lower respiratory tract involvement. The use of accessory muscles and the presence of retractions should be noted. A prolonged expiratory phase is associated with respiratory obstruction in the lower airways.

Chest: Look at the depth, ease, symmetry, and rhythm of respiration. These are key indicators of lower respiratory tract involvement. The use of accessory muscles and the presence of retractions should be noted. A prolonged expiratory phase is associated with respiratory obstruction in the lower airways.• Palpation or percussion (or both) of:

Paranasal and frontal sinus: Palpate for signs of sinus tenderness, knowing that this is a very insensitive physical assessment finding. Note: Take child’s age into consideration when determining likelihood of sinus pathology.

Paranasal and frontal sinus: Palpate for signs of sinus tenderness, knowing that this is a very insensitive physical assessment finding. Note: Take child’s age into consideration when determining likelihood of sinus pathology. Chest: Percuss for signs of dullness or hyperresonance caused by consolidation, fluid, or air trapping.

Chest: Percuss for signs of dullness or hyperresonance caused by consolidation, fluid, or air trapping. Upper tract: Pathology frequently causes noisy breathing, snoring, stridor, rhonchi and can be a source of referred breath sounds (Mellis, 2009).

Upper tract: Pathology frequently causes noisy breathing, snoring, stridor, rhonchi and can be a source of referred breath sounds (Mellis, 2009).Diagnostic Tests

• Monitoring oxygenation by pulse oximetry and blood gases:

Pulse oximetry can be used to continuously measure pulse rate and peripheral oxygen saturation in arterial blood. The oxyhemoglobin saturation percentage (Spo2) is digitally displayed. Results generally correlate well with simultaneous arterial saturation (Sao2). With anoxia, there is a rise in organic phosphate content within the red blood cells that results in more O2 available to tissues. People living at higher elevations suffer from chronic hypoxia. When first arriving at a high elevation, many individuals experience a transient mountain sickness with symptoms that include headache, insomnia, irritability, breathlessness, nausea, and vomiting. This phenomenon lasts approximately 1 week before acclimatization begins. The affected person begins to increase production of red blood cells (RBCs). Finally, a functional nonpathologic right ventricular hypertrophy takes place. These effects last as long as the person remains at high elevation. Severe altitude sickness can lead to cerebral and pulmonary edema and can be life-threatening.

Pulse oximetry can be used to continuously measure pulse rate and peripheral oxygen saturation in arterial blood. The oxyhemoglobin saturation percentage (Spo2) is digitally displayed. Results generally correlate well with simultaneous arterial saturation (Sao2). With anoxia, there is a rise in organic phosphate content within the red blood cells that results in more O2 available to tissues. People living at higher elevations suffer from chronic hypoxia. When first arriving at a high elevation, many individuals experience a transient mountain sickness with symptoms that include headache, insomnia, irritability, breathlessness, nausea, and vomiting. This phenomenon lasts approximately 1 week before acclimatization begins. The affected person begins to increase production of red blood cells (RBCs). Finally, a functional nonpathologic right ventricular hypertrophy takes place. These effects last as long as the person remains at high elevation. Severe altitude sickness can lead to cerebral and pulmonary edema and can be life-threatening. Blood gas studies can help the provider assess possible respiratory collapse and are used in acute care settings. A rising Paco2 is an ominous sign.

Blood gas studies can help the provider assess possible respiratory collapse and are used in acute care settings. A rising Paco2 is an ominous sign.• Unless there is chronic or complicated rhinosinusitis, imaging in acute rhinosinusitis remains controversial because uncomplicated URIs can cause abnormalities of the paranasal sinuses (Cherry and Shapiro, 2010; DeMuri and Wald, 2010). Radiographic imaging in respiratory disease may be necessary, including radiographs, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) of the sinuses, soft tissues of the neck, and chest. Abnormalities of the nasal mucosa such as thickening may reflect inflammation. Chest radiographs should be done in both posteroanterior and lateral positions because lesions may only be seen in one of the two views. Fluoroscopy is useful in the evaluation of stridor and abnormal movement of the diaphragm. Several other pulmonary studies may be ordered by the medical specialists to whom the child is referred. Contrast studies (e.g., barium esophagogram) are useful for patients with recurrent pneumonia, persistent cough, tracheal ring, or suspected fistulas. Other imaging studies that might be needed to assess these children include bronchograms (useful in delineating the smaller airways), pulmonary arteriograms (evaluation of the pulmonary vasculature), and radionuclide studies (evaluation of the pulmonary capillary bed). Pulmonary function tests are discussed in Chapter 24 in the section on asthma.

• Other specialized tests, including sweat testing, cultures and blood work, are addressed under the specific illness.

• Endoscopy (bronchoscopy and laryngoscopy), bronchoalveolar lavage, percutaneous tap, lung biopsy, and microbiology studies are other helpful diagnostic procedures if used appropriately. Children who have unusual signs and symptoms that require such procedures should be referred to medical specialists.

Basic Respiratory Management Strategies

Basic Respiratory Management Strategies

General Measures

• Fluid. Hydration is important to keep mucous membranes and secretions moist. Intake of fluids should be encouraged and parents of young children should be given guidelines regarding the type, amount, and frequency of fluids and feedings that their child should take.

• Oxygen administration. The use of supplemental oxygen is important to help relieve hypoxemia in most children who have acute respiratory distress. Depression of the respiratory drive is possible with supplemental oxygen administration if the central nervous system (CNS) chemoreceptors are blunted by hypercapnia. However, children at risk for blunting are those with issues related to chronic hypercapnia and are generally easily recognized because they tend to have chronic severe respiratory diseases such as CF and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. In acute situations, administer oxygen using an appropriately sized mask or a high-flow O2 source held near the child’s face if a mask frightens the child. The safe, acceptable range of O2 saturation is 92% to 95%; higher levels may lead to oxygen toxicity (Chin, 2010; Robinson and Van Asperen, 2009). Children seen in primary care settings who require supplemental oxygen should be transported to an acute care hospital setting via emergency medical services for evaluation and stabilization.

• Humidification. For a child with laryngotracheobronchitis (LTB), taking the child out into the cold night air or opening a freezer door may be beneficial. There is no evidence for the use of steam or humidification in croup (Everard, 2009). A cold-mist vaporizer helps provide moisture to the nares and oropharynx during a common cold, but the vaporizer must be cleaned daily so that it will not become a source of infection.

• Bulb syringe. Because infants are obligate nose breathers, parents should be instructed in use of the nasal bulb syringe to relieve obstruction of the infant’s nares with mucus. Use the bulb syringe gently and intermittently because improper use can cause irritation, inflammation, and respiratory obstruction from tissue damage. Providing parents with written instruction on suctioning the infant’s nose with a bulb syringe is advantageous. Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center has home instructions for this technique available on its website.

• Normal saline nose drops, nasal rinses, or spray. Use before feedings and when mucus is thick or crusted. Follow by suctioning the nares with a bulb syringe. Saline nasal rinses are widely available commercially and are helpful for older children and adolescents.

Medications

The following pharmacologic agents may be needed to treat various respiratory illnesses:

• Antibiotics. Specific agents are discussed in the section on individual illnesses. If an antibiotic is prescribed, the drug should be taken until completed.

• Analgesics and antipyretics. Acetaminophen and ibuprofen may be prescribed for relief of pain or fever.

• Decongestants and antihistamines. The use of decongestants and antihistamines does not shorten the course of a disease, but can provide relief of nasal symptoms. However, due to the risk of overdosage and unsupervised ingestions, these agents should not be used in children younger than 4 years of age (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2008). Practitioners need to use caution in prescribing these agents in children younger than 6 years.

• Expectorants. Water is one of the most effective expectorants. Over-the-counter agents provide some symptomatic relief, but do not shorten the course of respiratory illnesses. Do not use in children younger than 4 years (CDC, 2008).

• Cough medication. Cough suppressant medications should be prescribed judiciously because coughing is a protective mechanism to clear secretions. In review of evidence-based guidelines for the intervention in pediatric cough, the only cough medication that was recommended was honey, provided the child was more than 1 year old (Chang, 2009). However, the study results may be the result of a placebo effect (Paul et al, 2007).

Patient and Parent Education

Frequent handwashing and avoiding touching eyes and nose can help prevent the spread of infection. Parents should be educated about assessment and management of changes in the child’s condition. Significant educational issues are identified in Box 31-1.

BOX 31-1 Parental Education for At-Home Care of the Child With a Respiratory Tract Infection

Infection: Issues to Discuss

Fluid: Give guidelines on type, amount, and frequency of fluids child should take.

Bulb syringe: Instruct to use the bulb syringe gently and intermittently for suctioning the nares.

Other educational issues to cover:

• Indications for immediate reevaluation of child:

• Information on when to expect improvement in the child’s symptoms and, if symptoms do not improve as expected, what to do next

• Clear instructions about medications—how much to give, when to give, side effects to watch for, how long to give, and the necessity of completing the course of antibiotics

• Infection control information if needed—handwashing and disposal of infected secretions; the CDC has excellent written and video education materials available on handwashing at www.cdc.gov/Features/HandWashing.

• Care of nebulizers and humidifiers—to prevent the growth of organisms, nebulizers and humidifiers should be cleaned daily with soapy water, rinsed thoroughly, soaked for one half hour in a solution of one part vinegar to two or three parts distilled water, and then air-dried. Control III® disinfectant is a commercial product that can be substituted for vinegar; however, it is expensive.

Indications for Tonsillectomy and Adenoidectomy

Indications for Tonsillectomy and Adenoidectomy

Controversy remains about the need for tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy, or both, particularly for less affected children (Burton and Glasziou, 2009). Tonsillectomy has been found to be beneficial in children who are severely affected with recurrent tonsillitis (Morris, 2009). Tonsillectomy may be helpful in the syndrome of periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis (PFAPA syndrome) (Garavello et al, 2009; Licameli et al, 2008) and in obstructive sleep apnea. The provider must weigh the pros and cons of recommending a tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy, or both and consider whether a wait-and-see approach is the best strategy to determine if growth and time will negate the need for surgery (Burton and Glasziou, 2009). Cold steel tonsillectomy is associated with less pain and bleeding postoperatively than the traditional method of diathermy (Morris, 2009).

Upper Respiratory Tract Disorders

Upper Respiratory Tract Disorders

The Common Cold

Clinical Findings

Physical Examination

Virus-specific findings include:

Differential Diagnosis

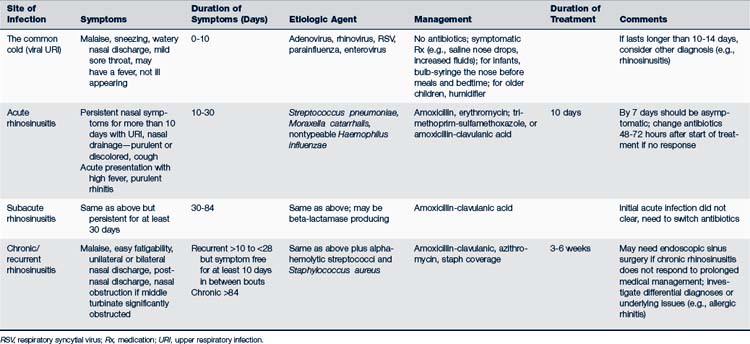

The most common differentials are allergic rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, and adenoiditis (Table 31-2). Colds can be associated with pharyngitis or, when tonsillar involvement is significant, tonsillopharyngitis (tonsillitis). When tonsillar involvement is minor, the term nasopharyngitis is used.

Pharyngitis, Tonsillitis, and Tonsillopharyngitis

Acute Viral Pharyngitis, Tonsillitis or Tonsillopharyngitis

Clinical Findings

Physical Examination

Virus-specific physical findings include the following:

• EBV can produce exudate on the tonsils, soft palate petechiae, and diffuse adenopathy.

• Adenovirus can cause a follicular pattern on the pharynx (Cherry, 2010a).

• Enterovirus can produce vesicles or ulcers on the tonsillar pillars and posterior fauces; coryza, vomiting, or diarrhea may be present.

• Herpesvirus produces ulcers anteriorly and marked adenopathy.

• Parainfluenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) cause more lower respiratory tract disease (e.g., croup, pneumonia, and bronchiolitis) with their typical respiratory signs of stridor, rales, or wheezing.

Acute Bacterial Pharyngitis and Tonsillitis

Clinical Findings

History

The following characterize GABHS infection:

• Most commonly found in 5- to 15-year-old children; infrequent in children younger than 2 years old

• Abrupt onset without nasal symptoms

• Constitutional symptoms such as arthralgia, myalgia, headache

• Moderate to high fever, malaise, prominent sore throat, dysphagia

• Nausea, abdominal discomfort, vomiting, headache

• Presentation in late winter or early spring

• N. gonorrhoeae (GC) has no distinctive finding on examination from other pharyngitis.

• Lack of a cough or nasal symptoms, along with an exudative, erythematous pharyngitis with a follicular pattern and typical historical findings point to GABHS.

• A. haemolyticum causes an exudative pharyngitis with marked erythema and a pruritic, fine, scarlatiniform rash (Martin, 2010).

Physical Examination

• Petechiae on soft palate and pharynx, swollen beefy-red uvula, red enlarged tonsillopharyngeal tissue

• Tonsillopharyngeal exudate that is yellow, blood-tinged (frequently)

• Tender and enlarged anterior cervical lymph nodes

• Stigmata of scarlet fever may be seen—scarlatiniform rash, strawberry tongue, circumoral pallor

• Variable presentation; may have mild pharyngeal erythema without tonsillar exudate or cervical adenopathy

Management

• Antimicrobial therapy (based on clinical need)—one of the following (American Academy of Pediatrics [AAP], 2009; Gerber et al, 2009, Taketomo et al, 2011):

If evidence of penicillin resistance is present, a beta-lactamase–resistant antibiotic can be used, such as amoxicillin-clavulanate or dicloxacillin.

If evidence of penicillin resistance is present, a beta-lactamase–resistant antibiotic can be used, such as amoxicillin-clavulanate or dicloxacillin.• Supportive care—antipyretics, fluids, rest.

• Repeat culture is not generally needed except in situations in which it is necessary to ensure eradication of the organism.

• Continued symptoms of streptococcal pharyngitis and a positive culture for streptococcus may represent an actual treatment failure or a new infection with a different serologic type of streptococcus.

• Noncompliance with pharmacologic therapy can explain treatment failure, and in these instances, an injection of benzathine penicillin is recommended.

• For a compliant patient with recurrence, narrow-spectrum cephalosporins, clindamycin, or amoxicillin-clavulanic acid or a combination of penicillin with rifampin are reasonable alternatives (Gerber et al, 2009).

• If clinical relapse occurs, a second course of antibiotic is indicated, as discussed earlier. If recurrent infection is a problem, culturing of the family for the chronic carrier state is advised.

• Fomites such as bathroom cups, toothbrushes, or orthodontic devices may harbor GABHS and should be cleaned or discarded.

• Children can return to school when they are afebrile and have been taking antibiotics for at least 24 hours.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree