Chapter 69 Respiratory Conditions

ASTHMA

ETIOLOGY

What Are the Common Clinical Patterns of Asthma?

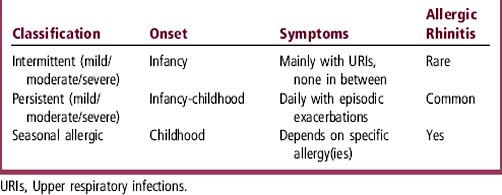

Intermittent asthma is the most common pattern of asthma in children. Other patterns are persistent asthma and seasonal allergic asthma (Table 69-1). Although the National Asthma guidelines classify intermittent asthma as “mild,” symptoms during an exacerbation of intermittent asthma in a child may be severe enough to warrant hospitalization. Therefore, intermittent asthma in childhood is best considered to have a range of severity from mild to severe. Young children commonly have a pattern of frequent, recurrent exacerbations of asthma, usually triggered by viral upper respiratory infections (URIs). Approximately 15% of children have 12 or more URIs a year, each of which may trigger an acute asthma exacerbation. This translates to approximately one URI-triggered asthma “attack” every 3 to 4 weeks for many young asthmatics during the fall and winter viral infection season. The frequency of URI-induced exacerbations makes the distinction between intermittent and persistent asthma difficult in infants and toddlers.

What Are Common Triggers for Childhood Asthma?

Table 69-2 shows common triggers for asthma and their usual timing. All patterns of asthma can be exacerbated by viral illnesses. Up to 85% of acute exacerbations that require emergency department (ED) or hospital care are associated with viral illnesses.

Table 69-2 Common Triggers for Asthma

| Cause | Season |

|---|---|

| Viral illness | Fall–spring |

| Exercise | With exercise, year-round |

| Irritant (smoke, perfume, etc.) | With exposure, year-round |

| Cold air | Winter |

| Allergies | |

|---|---|

| Molds | Spring and fall |

| Pollens | Spring–summer |

| Cats/dogs | Year-round |

| Grasses | Spring–summer |

| Dust mites | Year-round |

| Cockroaches | Year-round |

EVALUATION

What History and Examination Findings Are Important?

The asthmatic child or adolescent often comes to attention because of cough (see Chapter 25). Table 69-3 shows important history and physical findings in asthma. Asthma diagnosis is primarily made from the patient’s history and response to medications.

| History | Physical Examination |

|---|---|

| Response to albuterol (immediate) | Increased respiratory rate |

| Response to oral steroids (1-3 days) | Expiratory wheezing |

| Symptoms between exacerbations | Decreased air movement during forced expiration |

| Triggers of asthma | Increased expiratory phase |

| Frequency and timing of exacerbations | Anxiety, fatigue, or confusion |

| History of intubations, ICU hospitalizations, or ED visits | Nasal flaring, retractions, and accessory muscle use |

| Cough at night | Inability to speak in complete sentences |

| Cough with exercise | Eczema |

| Allergic rhinitis symptoms | |

| Pet and tobacco exposures | |

| Family history of asthma |

ED, Emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

TREATMENT

When Should an Asthmatic Be Hospitalized?

Most asthmatics can be treated as outpatients. Table 69-4 shows key reasons for hospitalization.

Table 69-4 Criteria for Hospital Admission in Asthma

| Critically ill |

| Severe airway obstruction with respiratory distress |

| Increased PaCO2 |

| Poor response to emergency department therapies |

| Greater than 3 or 4 bronchodilator treatments |

| Oxygen saturations < 90% |

| Social considerations |

| Unreliable parents, transportation, or telephone |

| Home is far from nearest medical facility |

What Are the Side Effects of Steroids?

Short courses of oral steroids generally have minor, but often distressing, temporary side effects that include increased appetite, irritability, joint aches, and stomach ache. If steroids must be used frequently in short courses or for prolonged courses (> 14 days), more prominent side effects may occur, including Cushingoid features and hyperglycemia. Table 69-5 shows common corticosteroid side effects. Oral steroids also have a bitter taste, which complicates adherence to the treatment plans for young children.

Table 69-5 Corticosteroid Side Effects

| Minor | Major |

|---|---|

| Behavior changes | Growth suppression |

| Sleep disturbances | Osteoporosis |

| Appetite changes (usually increase) | Hypothalamic-pituitary axis suppression |

| Acne or puffy red cheeks | Cushingoid appearance |

| Gastrointestinal upset and bowel habit changes | Skin thinning or striae |

| Oropharyngeal candidiasis (inhaled steroids) | Hirsutism |

| Joint aches | Immunosuppression |

| Weight gain | Hyperglycemia |

How Do I Choose a Medication for Persistent Asthma?

Table 69-6 lists different classes of maintenance medications for persistent asthma and shows some advantages and disadvantages of each. Inhaled steroids are generally the first line treatment for persistent asthma. The newer inhaled steroids—budesonide (Pulmicort), fluticasone (Flovent), or beclomethasone HFA (Qvar)—are more effective at lower doses than older preparations. Although long-acting beta-agonists are not as effective as inhaled steroids for monotherapy, medications such as salmeterol (Serevent) act synergistically with inhaled steroids and allow a decrease in steroid dose. They are available in combination with inhaled steroids, such as fluticasone/salmeterol (Advair). Recently, a small but significant increase in asthma-related deaths or life-threatening experiences was found in African-Americans older than 12 years using salmeterol in addition to their usual asthma care (Nelson et al., 2006). Montelukast (Singulair) is the preferred leukotriene modifier because it is a once-a-day medication with almost no side effects. Other leukotriene modifiers are either more difficult to administer or have more side effects: zileuton (Zyflo) must be given four times a day and can have hepatotoxicity, and zafirlukast (Accolate) must be given twice a day and has some drug-drug interactions. Mast cell stabilizers, cromolyn (Intal) and nedocromil (Tilade), have almost no effective role in the treatment of childhood asthma. Although theophylline (Theo-Dur, Slo-bid) is effective, it is not often prescribed because of the potential side effects and narrow therapeutic window.

Table 69-6 Maintenance Medications for Asthma

| Class | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Inhaled steroid | Daily-BID dosing Long half-life | Can have growth suppression at high doses |

| Long-acting beta-agonists | BID dosing | Less effective as monotherapy |

| Small but significant increase in asthma-related deaths, especially in African-Americans | ||

| Combination therapy: inhaled steroids and long-acting beta-agonists | Improved control with lower inhaled steroid doses | Both inhaled steroid and long-acting beta-agonist disadvantages |

| Antiinflammatory + bronchodilator | ||

| Leukotriene modifiers | Oral medication | Usually only effective in mild persistent asthmatics |

| Few side effects (Singulair) | ||

| Theophylline | Oral medication | Narrow therapeutic window |

| Requires drug levels | ||

| Mast cell stabilizers | Minimal side effects | Minimal therapeutic effects |

| QID dosing |

BID, Twice per day; QID, four times per day.

BRONCHIOLITIS

EVALUATION

What History and Examination Findings Are Important?

History and examination findings for bronchiolitis are shown in Table 69-7.

Table 69-7 Findings in Bronchiolitis

| History | Physical Examination |

|---|---|

| Viral prodrome | Expiratory wheezing and/or crackles |

| Copious rhinorrhea | Tachypnea (> 60 breaths/min) |

| Poor feeding | Respiratory distress (grunting, nasal flaring, retractions, etc.) |

| Apneic episodes (> 20 sec) | Lethargy and fatigue |

| Cyanosis | Signs of dehydration |

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree