59 Renal Neoplasms

Etiology and Pathogenesis

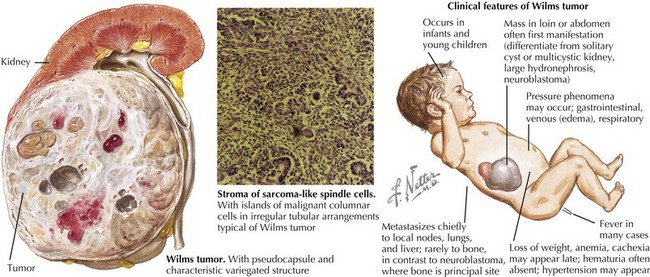

Wilms’ Tumor

Wilms’ tumor accounts for the majority (85%) of pediatric renal tumors with 500 new cases per year in the United States (Figure 59-1). The more aggressive anaplastic histologic subtype of Wilms’ makes up about 8% of all pediatric renal tumors. The mean age at presentation is 3 to 4 years for unilateral disease, and the majority of patients are younger than 10 years old at diagnosis. Patients with bilateral disease account for 5% of all Wilms’ cases and present younger than those for unilateral disease at 2 to 2.5 years of age.