A speech and language therapist focuses on communication, swallowing, and speech production, and has a number of goals. One of the most basic goals is to find or create a way of identifying wants and needs. For example, utilizing a series of pictures may be beneficial to a patient with a dense aphasia. Another communication goal would be the ability to call staff using a call bell. Further communication goals might be speech production and better strategies to articulate for a dysarthric patient. For the patient’s dysphagia, there may be swallowing trials with different textures of food, so that the goal of swallowing safely can be pursued systematically. Adaptive equipment and strategies need to be developmentally appropriate. For instance, communication boards may utilize pictures to point to rather than letters.

PT usually focuses on gross motor activity and mobility goals, but this is not limited to safe ambulation or wheelchair use. For our stroke patient, PT goals would include bed mobility, transfers, posture, and mobility for self-care. Only after those initial goals are partially achieved can actual gait training begin. The PT would also eventually help order any needed bracing devices, assistive devices (e.g., cane, crutch, or walker) or mobility devices (e.g., wheelchair).

OT usually focuses on fine motor skills, but also works on specific vocational or recreational goals and academic strategies that would be helpful in almost any classroom. OT would work with our stroke patient to strengthen his hemiplegic arm as motor activity returns, but a more preliminary goal might be to develop strategies for managing activities of daily living in the setting of hemiplegia.

Many goals noted in the acute rehabilitation setting involve multiple members of the team. Memory-based tasks for example are reinforced in PT, OT, and speech therapy but are also stressed by nursing and with child life specialists or music or art therapists. Self-care goals and many activities of daily living are usually pursued in all of these settings as well. Cognitive retraining for children with new cognitive deficits is primarily addressed in OT, speech and language therapy, and with whatever classroom setting is available. However, all of the therapists ideally would reinforce the cognitive-based goals. This is the nature of this multidisciplinary rehabilitation team.

■ BASELINE STATUS

Understanding a patient’s “baseline functional status” is of particular importance to rehabilitation. The goals of a rehabilitation plan of care hinge on baseline status. An example will help to illustrate its importance:

Two 13-year-old girls who sustained moderate to severe traumatic brain injuries are stabilized in the intensive care unit (ICU). Both are left with cognitive deficits, confused, inappropriate at times, and are in need of assistance for activities of daily living. In terms of baseline functional status, one of the girls carries a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis and was presumed to have moderate to severe intellectual disability, while the other reportedly had “some difficulty in school” prior to her accident but had no medical illness or syndrome. After a more careful evaluation of the situation it was found that the girl with tuberous sclerosis actually had an IQ of 80 at baseline and the other young woman labeled with “learning difficulties” had an IQ of 60, an individual education plan, and was in a life-skills classroom setting. Neurocognitive testing postacutely revealed that the girl with tuberous sclerosis was well below her baseline, yet many on the treating team mistakenly presumed she was at her baseline in 24 hours after her trauma. The same evaluation on the other girl revealed that she was actually at her baseline the day after her injury. She actually was never age appropriate for her activities of daily living even prior to her traumatic brain injury.

The girl with tuberous sclerosis had almost been discharged without any potentially beneficial inpatient rehabilitation. The other girl actually was transferred to inpatient rehabilitation and it was not until a week later that her individualized educational plan was obtained, showing that she had been at her baseline the entire time.

For many children with a neurologic injury, however, there is a decline that may ultimately limit their neurocognitive potential. A careful and thoughtful evaluation of their projected new baseline status is required. When it can be predicted that a child will have new limitations on his neurocognitive potential following brain injury, then this must be taken into account when establishing goals for rehabilitation. This is perhaps most important for the family of that child, so that they can have a realistic view of the potential outcome and new needs of their child.

Alternately, a change in cognition can be easily overlooked by both the ICU team and the family. A common scenario where such changes go unrecognized occurs in patients with a spinal cord injury and coexisting traumatic brain injury. If subtle, the traumatic brain injury may go unrecognized because of the readily apparent (and distressing) paresis that may exist. These brain injuries may be missed, despite the fact that up to 60% of spinal cord injury patients also have evidence of a traumatic brain injury (2). Over 30% of these co-occurring traumatic brain injuries are mild, and this more subtle presentation may lead to lack of brain injury identification upon presentation.

■ EARLY REFERENCE POINTS

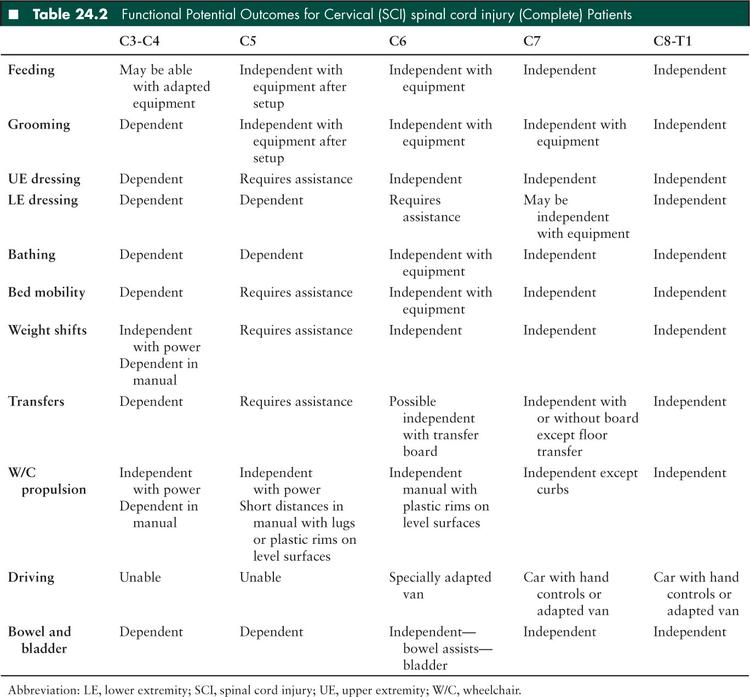

Clinical outcomes remain difficult to predict early in the course of a neurologic injury, when the patient is still in the critical care unit. The literature on spinal cord injury has provided some good evidence for predicting the functional status that may be attained by a patient (Table 24.2). This table may serve as an aid to early discussions about prognosis which may occur in the critical care unit. Translating medical terms regarding function into layman’s terms is far more meaningful to a patient and his or her family.

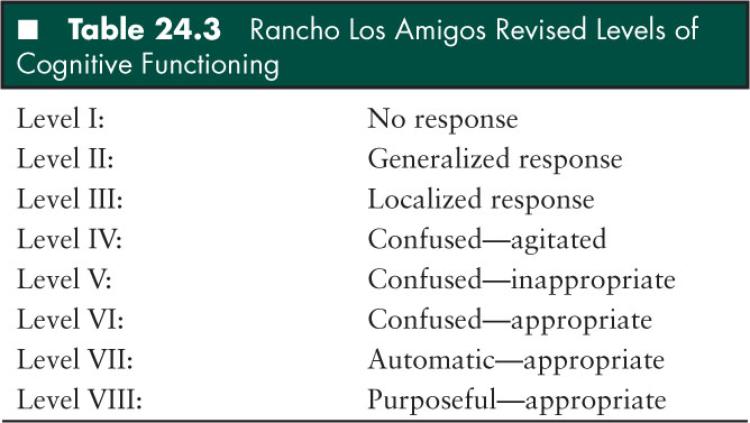

Outcomes following brain injury often prove more difficult to predict. The complexity both in terms of pathophysiology and premorbid function, superimposed on developmental age make prognosticating a problem for both the clinician and the family. In the short term however, the Rancho Los Amigos Scale (Table 24.3) may be helpful in describing cognitive function. In the presence of a noncommunicative patient, parental distress is often decreased in a small but significant way by thinking of “stages” of brain injury recovery. Progression in the levels represents improvement, even though the scale is nonlinear. Both clinicians and families often need to be reminded that there is not a clear duration for each of these levels, and that some levels can be bypassed by a patient, and some patients may plateau at certain levels. Lastly, these levels can be tracked by the care team to objectify some of the findings.

■ TIMING/WHEN TO CONSULT

While the immediate issues of medical management of a neurocritical care patient are the first priority, rehabilitation concerns can and must be addressed early. Several studies have shown worse outcomes with delays in rehabilitation. One study demonstrated that delays in admitting children with critical brain injuries from an ICU to an appropriate rehabilitation facility correlated with a less efficient rehabilitation course with significantly less measurable improvement in their functional measures (3). Early rehabilitation for adult brain injury patients has been shown to improve outcomes and decrease postacute rehabilitation duration (4) as well as reduce overall hospitalization costs (5). Similarly, earlier initiation of rehabilitation following adult stroke results in better functional outcome scores (6). Multiple adult studies have noted better outcome metrics with earlier or more intense rehabilitation.

Rehabilitation is not a separate phase of care that begins after medical management has been optimized and completed. Very little effective rehabilitation is likely to get done during the golden hour of trauma resuscitation or during status epilepticus, but there are multiple reasons to involve the rehabilitation team early in the course of any critical care stay, especially in the neurocritical care setting. Furthermore, a large percentage of patients presenting to a neurocritical care unit have ongoing rehabilitation needs, but are admitted for other acute medical illnesses. One recent study of hospitalized children in neonatal and pediatric ICUs in France reported that the prevalence of preexisting chronic conditions and disability was 67% (7), and a similar study in the United States found that number to be slightly greater than 50% (8). This would imply that this subset of the patients in a neurocritical care unit have regular, ongoing need for rehabilitative services. These patients likely were getting some of these services prior to admission, and now there has been some neurologic decline which may warrant additional therapy.

■ WHOM TO CONSULT—THE COMPOSITION OF THE REHABILITATION TEAM

The rehabilitation team is composed of (but certainly not limited to) the rehabilitation physician (also known as a physiatrist or specialist in physical medicine and rehabilitation), speech therapist, occupational therapist (OT), physical therapist (PT), and a recreation specialist (sometimes referred to as a “child life specialist”). Others that are considered part of the team include nursing, family, social work, teacher/academic specialist, rehabilitation engineering specialist, orthotist, prosthetist, and mental health professional such as psychologist and psychiatrist.

Early consultation is recommended, but patient stability, access to the patient, and medical or diagnostic procedures each potentially delay how early this can occur. In many circumstances consultation by speech therapy, OT, and PT can be requested simultaneously with the physiatrist consultation. More often, however, in the early course of such an admission, the needs and goals are difficult to identify and consultation with the physiatrist can help to crystallize the initial rehabilitation plan and recommend which members of the team need to be involved most urgently. Furthermore, it has been reported that review by a rehabilitation physician significantly improves the chance of referral to formal rehabilitation (9).

■ REHABILITATION’S IMPACT DURING THE ICU COURSE

Involvement of the rehabilitation team in the ICU has important impact on the team and the course of an illness that is less direct and more difficult to quantify. Several of these benefits deserve mention:

Giving the patient and family a more active role in their recovery. Often there is little or no ability for the family to participate in their own care, but in PT, OT, or speech therapy, the patient and/or family are asked to participate.

Facilitating self-care. This leads to less helplessness and more independence.

Facilitating early communication. Helping to interpret when the ability to communicate is limited is an everyday occurrence for a skilled speech therapist and can be key in determining care as well as assuring caregivers.

Laying the groundwork for the rehabilitation over the subsequent months by informing the family about the timing and details of recommended therapies, and giving an example of the daily routine of a rehabilitation unit or an outpatient rehabilitation program.

■ FACTORS THAT LIMIT REHABILITATION

In the neurocritical care setting, there are many common medical and physical limitations that can be barriers for the rehabilitation team. For example, caution over blood pressure control and cerebral perfusion often limit the amount of physical activity, either active or passive, that a patient can tolerate. Positioning can also be an issue for many therapeutic interventions, such as when the patient is required to lay supine without any elevation of the head of the bed. Sometimes the patient is limited in terms of positioning for intracranial pressure monitoring or cerebrospinal fluid drainage.

Endotracheal intubation is another common limitation to early rehabilitation. While this is physically limiting and potentially uncomfortable for the patient, it does not always make them ineligible for PT, OT, or even speech therapy. While phonation is not a reasonable goal in this circumstance, communication may be achieved. A speech therapist can help to facilitate communication in an intubated patient using augmentative or alternative strategies. Often this evaluation benefits the entire care team because nonverbal communication might be the only means of assessing mental status. The consistency and the skill of a speech therapist often produces some of the most reliable insights into the patient’s cognitive status, their wishes, and their psychological state in such a circumstance.

Another common limitation is patient tolerance of therapies. Pain, fatigue, nausea, weakness, mood disturbance, and many other issues make it difficult for a patient to tolerate therapy that will ultimately benefit them. Those problems must be addressed to both improve overall care and allow the earliest possible initiation of rehabilitation therapy. Regional anesthetic techniques such as nerve blocks can occasionally be utilized to minimize pain, maximize mobility, and minimize sedation.

Paroxysmal autonomic instability with dystonia syndrome, also referred to as “storming,” is due to hypothalamic-midbrain dysregulation, diencephalic seizures, and sympathetic storming. This phenomenon is a common occurrence in a neurocritical care unit, and is most often seen following traumatic or anoxic brain injury. This is thought to be due to mesencephalic injury leading to dysregulation of normal autonomic function (10). It is sometimes responsive to medications, but it is often difficult to control, and not very well understood. Regardless of the name used, therapies are often discontinued when these episodes occur due to changes in blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, and the distressed appearance of the patient. Furthermore, episodes of this type can be initiated by noxious stimuli or relatively benign stimuli. Storming episodes can be initiated by something as seemingly innocuous as range of motion exercises from a PT or OT. Early on, this usually leads to stopping a therapeutic session until the symptoms subside, but for some, the dysautonomia persists and it must be decided how much stress the patient can tolerate. Labile blood pressure is undesirable during acute management, but if the primary manifestations are diaphoresis and changes in muscle tone, then often therapy can and should continue.

■ REHABILITATION-SPECIFIC MEDICAL ISSUES

Following is a brief overview of a few of the many medical issues that are commonly seen in acute rehabilitation, but that generally have their roots in the neurocritical care unit.

Seizure management is discussed in detail in Chapter 8. Most recommendations from the rehabilitation literature for management of seizures related to a traumatic brain injury do not recommend long-term prophylactic therapy. When seizures do need to be treated, anticonvulsants that do not significantly impair cognition or cause sedation are ideal for cognitive rehabilitation goals.

Heterotopic ossification (HO) is a form of abnormal calcification within soft tissues that can occur following spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, or burns, and can inhibit function. HO can be seen in up to 22% of severe pediatric traumatic brain injury cases. It can begin in the weeks after a traumatic brain injury, but usually does not have much clinical significance until after a patient is out of the neurocritical care unit. In approximately 20% of these patients the presence of HO may physically impede the rehabilitation process (11).

Deep-venous thrombosis is also a rare, but important problem following traumatic brain injury or spinal cord injury in the pediatric age groups. Medical prophylaxis with anticoagulants is effective, and recommended in some populations based on risk factors (12).

Fatigue and disturbance of normal sleep/wake cycle are common problems in any ICU that can persist as problems in an acute rehabilitation setting. In the traumatic brain injury population, these problems are particularly prevalent, even weeks after injury and it appears to be multifactorial (13). The initial treatment should be improved sleep hygiene, but medication may be needed. Melatonin can assist in optimizing sleep hygiene, and trazodone is widely used in the traumatic brain injury population.

Problems of arousal and attention are also common following many of the disorders seen in a neurocritical care unit that often continue to be problematic in the acute rehabilitation setting. This is a very complex issue and sedating medications are often a factor. The judicious uses of psychostimulants such as methylphenidate or dextroamphetamine often produce positive results. Current research in adults suggest that twice per day methylphenidate has clinically significant positive effects on processing speed in individuals with attentional complaints after traumatic brain injury (14). Early medical treatment of arousal issues and sleep disturbances is often problematic because of the environmental disturbances that cannot be avoided such as monitors, painful procedures, and the occurrence of around-the-clock care. Many of these disturbances are reduced or eliminated in a rehabilitation unit. In addition, the evaluation and treatment of these particular problems is much easier when there is a more routine schedule for these patients on a rehabilitation unit.

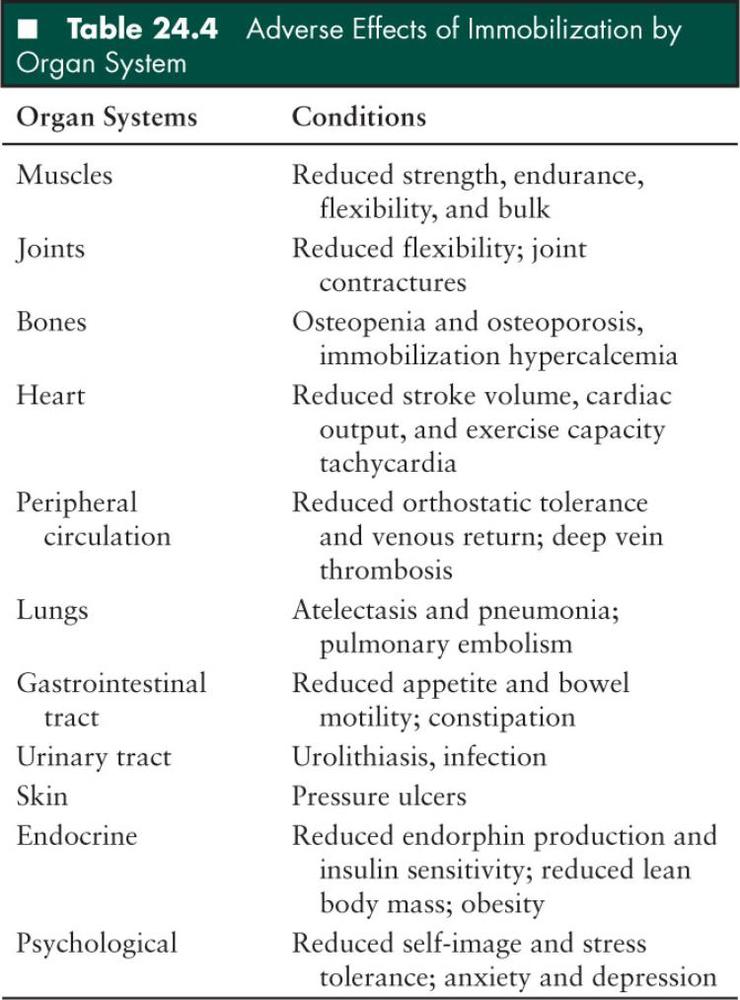

Immobilization’s negative effects are many fold and can be profound. These effects can be seen in most organ systems (Table 24.4). Many of the effects of immobilization can be delayed or completely prevented with hard work from the entire team, and most specifically the therapists and nurses. Operating within the confines of procedures and constraints of neurocritical care, this generally consists of proper positioning, range of motion exercises, splinting, and pressure relief. Active exercise by the patient, good pulmonary toilet, and weight bearing are all elements of optimal care. Immobilization hypercalcemia can exacerbate other organ system dysfunction and can be minimized by weight bearing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree