Chapter 401 Pulmonary Embolism, Infarction, and Hemorrhage

401.1 Pulmonary Embolus and Infarction

Venous thromboembolic disease (VTE) is well described in children and adolescents with or without risk factors (Table 401-1). Improvements in therapeutics for childhood illnesses and increased survival with chronic illness may contribute to the larger number of children presenting with thromboembolic events, which can be a significant source of morbidity and mortality.

Table 401-1 RISK FACTORS FOR PULMONARY EMBOLISM

ENVIRONMENTAL

WOMEN’S HEALTH

MEDICAL ILLNESS

SURGICAL

THROMBOPHILIA

NONTHROMBOTIC

Modified from Goldhaber SZ: Pulmonary embolism, Lancet 363:1295–1305, 2004.

Etiology

Commonly appreciated risk factors for thromboembolic disease in adults include immobility, malignancy, pregnancy, infection, and hypercoagulability; up to 20% of adults with this disorder may have no identifiable risk factor (see Table 401-1). Children with deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) are much more likely to have 1 or more identifiable conditions or circumstances placing them at risk. In a large Canadian registry, 96% of pediatric patients were found to have 1 risk factor and 90% had 2 or more risk factors.

Prothrombotic disease can also manifest in older infants and children. Disease can be congenital or acquired; DVT/PE may be the initial presentation. Factor V Leiden mutation (Chapter 472), hyperhomocysteinemia (Chapter 79.3), prothrombin 20210A mutation (Chapter 472), anticardiolipin antibody, and elevated values of lipoprotein A have all been linked to thromboembolic disease. Children with sickle cell disease are also at high risk for pulmonary embolus and infarction. Acquired prothrombotic disease is represented by nephrotic syndrome (Chapter 521) and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. From one quarter to one half of children with systemic lupus erythematosus (Chapter 152) have thromboembolic disease.

Epidemiology

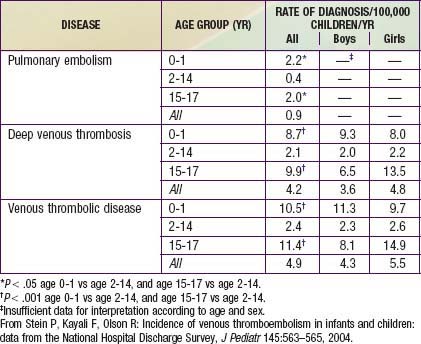

Younger age appears to be somewhat protective in thromboembolic disease. The DVT incidence in 1 study of hospitalized children was 5.3/10,000 admissions. A study that analyzed data from 1979 through 2001 found 0.9 cases of PE per 100,000 children per yr, 4.2 cases of DVT per 100,000 children per yr, and 4.9 cases of VTE per 100,000 children per yr (Table 401-2).