Pathophysiology

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory airway syndrome with a major hereditary component. Increased airway responsiveness and persistent subacute inflammation have been associated with genes on chromosomes 5q that include cytokine gene clusters, β-adrenergic and glucocorticoid receptor genes, and the T-cell antigen receptor gene (Barnes, 2012). Asthma is heterogeneous, and there inevitably is an environmental allergic stimulant such as influenza or cigarette smoke in susceptible individuals (Bel, 2013).

The hallmarks of asthma are reversible airway obstruction from bronchial smooth muscle contraction, vascular congestion, tenacious mucus, and mucosal edema. There is mucosal infiltration with eosinophils, mast cells, and T lymphocytes that causes airway inflammation and increased responsiveness to numerous stimuli including irritants, viral infections, aspirin, cold air, and exercise. Several inflammatory mediators produced by these and other cells include histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, cytokines, and many others. IgE also plays a central role in pathophysiology (Strunk, 2006). Because F-series prostaglandins and ergonovine exacerbate asthma, these commonly used obstetrical drugs should be avoided if possible.

Clinical Course

Clinical Course

Asthma findings range from mild wheezing to severe bronchoconstriction, which obstructs airways and decreases airflow. These reduce the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio and the peak expiratory flow (PEF). The work of breathing progressively increases, and patients note chest tightness, wheezing, or breathlessness. Subsequent alterations in oxygenation primarily reflect ventilation–perfusion mismatching, because the distribution of airway narrowing is uneven.

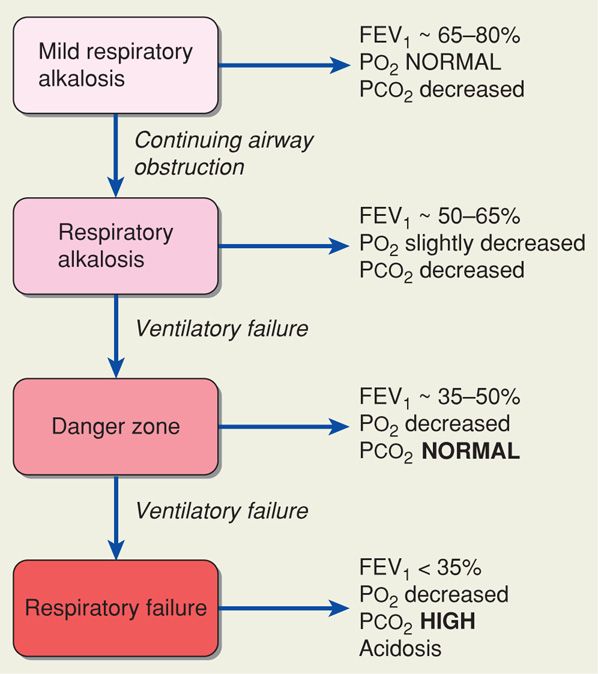

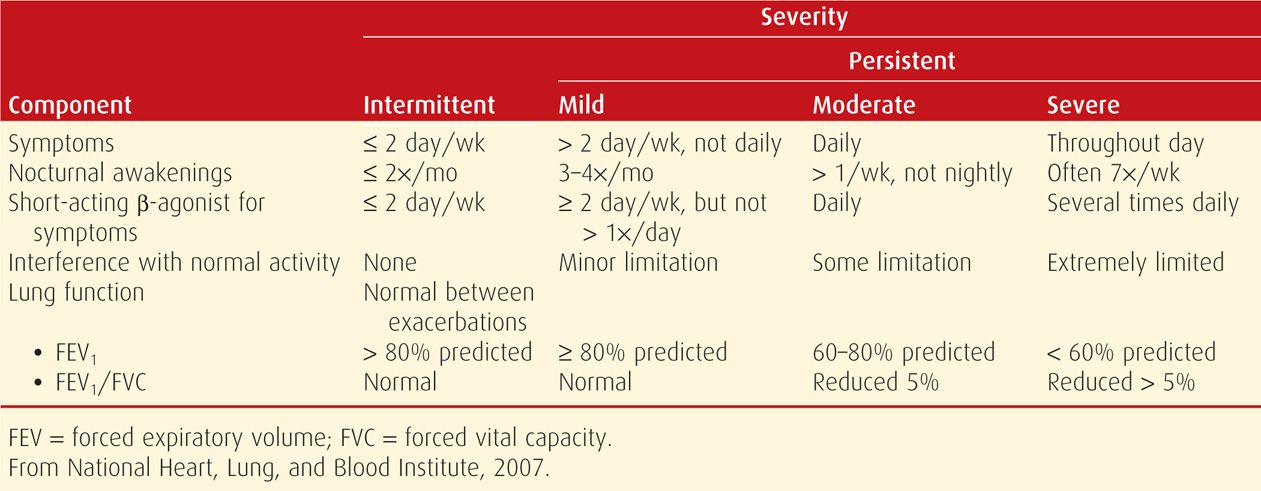

Varied manifestations of asthma have led to a simple classification that considers severity as well as onset and duration of symptoms (Table 51-1). With persistent or worsening bronchial obstruction, stages progress as shown in Figure 51-1. Hypoxia initially is well augmented by hyperventilation, which maintains arterial Po2 within a normal range while causing the Pco2 to decrease with resultant respiratory alkalosis. As airway narrowing worsens, ventilation–perfusion defects increase, and arterial hypoxemia ensues. With severe obstruction, ventilation becomes impaired as fatigue causes early CO2 retention. Because of hyperventilation, this may only be seen initially as an arterial Pco2 returning to the normal range. With continuing obstruction, respiratory failure follows from fatigue.

TABLE 51-1. Classification of Asthma Severity

FIGURE 51-1 Clinical stages of asthma. FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

Although these changes are generally reversible and well tolerated by the healthy nonpregnant individual, even early asthma stages may be dangerous for the pregnant woman and her fetus. This is because smaller functional residual capacity and increased pulmary shunting render the woman more susceptible to hypoxia and hypoxemia.

Effects of Pregnancy on Asthma

There is no evidence that pregnancy has a predictable effect on underlying asthma. In their review of six prospective studies of more than 2000 pregnant women, Gluck and Gluck (2006) reported that approximately a third each improved, remained unchanged, or clearly worsened. Exacerbations are more common with severe disease (Ali, 2013). In a study by Schatz and associates (2003), baseline severity correlated with asthma morbidity during pregnancy. With mild disease, 13 percent of women had an exacerbation and 2.3 percent required admission; with moderate disease, these numbers were 26 and 7 percent; and for severe asthma, 52 and 27 percent. Others have reported similar observations (Charlton, 2013; Hendler, 2006; Murphy, 2005). Carroll and colleagues (2005) reported disparate morbidity in black compared with white women.

Some women have asthma exacerbations during labor and delivery. Up to 20 percent of women with mild or moderate asthma have been reported to have an intrapartum exacerbation (Schatz, 2003). Conversely, Wendel and associates (1996) reported exacerbations at the time of delivery in only 1 percent of women. Mabie and coworkers (1992) reported an 18-fold increased exacerbation risk following cesarean versus vaginal delivery.

Pregnancy Outcome

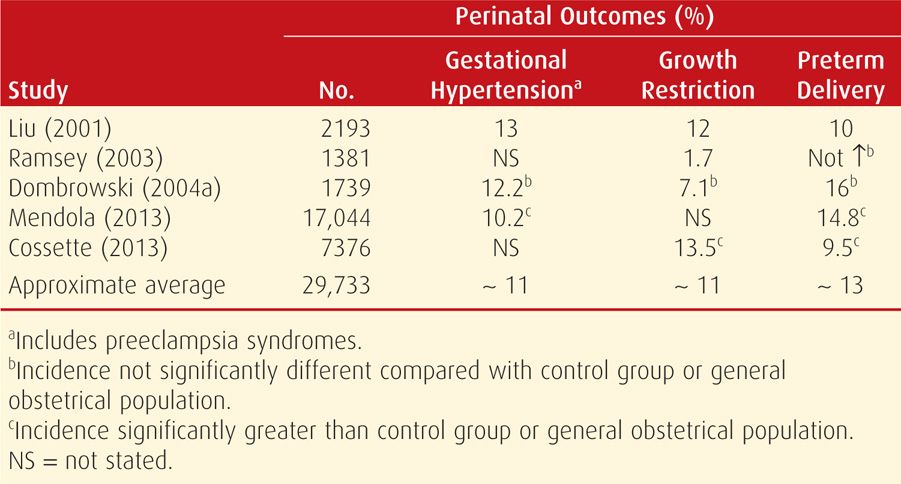

Women with asthma have had improved pregnancy outcomes during the past 20 years. From his review, Dombrowski (2006) concluded that, unless disease is severe, pregnancy outcomes are generally excellent. The incidence of spontaneous abortion in women with asthma may be slightly increased (Blais, 2013). Maternal and perinatal outcomes for nearly 30,000 pregnancies in asthmatic women are shown in Table 51-2. Findings are not consistent among these studies. For example, in some, but not all, incidences of preeclampsia, preterm labor, growth-restricted infants, and perinatal mortality are slightly increased (Murphy, 2011). Another report cited a small rise in the incidence of placental abruption and in preterm rupture of membranes (Getahun, 2006, 2007). But, in a European report of 37,585 pregnancies of women with asthma, the risks for most obstetrical complications were not increased (Tata, 2007). In the Canadian study in which inhaled-corticosteroid dosage was quantified, Cossette and coworkers (2013) found a nonsignificant trend between perinatal complications and increasing dosage. They concluded that low to moderate doses were not associated with perinatal risks and noted that more data were needed regarding higher doses.

TABLE 51-2. Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes in Pregnancies Complicated by Asthma

Thus, there appears to be significantly increased morbidity linked to severe disease, poor control, or both. In the study by the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network, delivery before 37 weeks’ gestation was not increased among the 1687 pregnancies of asthmatics compared with those of 881 controls (Dombrowski, 2004a). But for women with severe asthma, the rate was increased approximately twofold. In a prospective evaluation of 656 asthmatic pregnant women and 1052 pregnant controls, Triche and coworkers (2004) found that women with moderate to severe asthma, regardless of treatment, are at increased risk of preeclampsia. Finally, the MFMU Network study suggests a direct relationship of baseline pregnancy forced expiratory volume at 1 second (FEV1) with birthweight and an inverse relationship with rates of gestational hypertension and preterm delivery (Schatz, 2006).

Life-threatening complications from status asthmaticus include muscle fatigue with respiratory arrest, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, acute cor pulmonale, and cardiac arrhythmias. Maternal and perinatal mortality rates are substantively increased when mechanical ventilation is required.

Fetal Effects

With reasonable asthma control, perinatal outcomes are generally good. For example, in the MFMU Network study cited above, there were no significant adverse neonatal sequelae from asthma (Dombrowski, 2004a). The caveat is that severe asthma was uncommon in this closely monitored group. When respiratory alkalosis develops, both animal and human studies suggest that fetal hypoxemia develops well before the alkalosis compromises maternal oxygenation (Rolston, 1974). It is hypothesized that the fetus is jeopardized by decreased uterine blood flow, decreased maternal venous return, and an alkaline-induced leftward shift of the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve.

The fetal response to maternal hypoxemia is decreased umbilical blood flow, increased systemic and pulmonary vascular resistance, and decreased cardiac output. Observations by Bracken and colleagues (2003) confirm that the incidence of fetal-growth restriction increases with asthma severity. The realization that the fetus may be seriously compromised as asthma severity increases underscores the need for aggressive management. Monitoring the fetal response is, in effect, an indicator of maternal status.

Possible teratogenic or adverse fetal effects of drugs given to control asthma have been a concern. Fortunately, considerable data have accrued with no evidence that commonly used antiasthmatic drugs are harmful (Blais, 2007; Källén, 2007; Namazy, 2006). Thus, it is worrisome that Enriquez and coworkers (2006) reported a 13- to 54-percent patient-generated decrease in β-agonist and corticosteroid use between 5 and 13 weeks’ gestation.

Clinical Evaluation

Clinical Evaluation

The subjective severity of asthma frequently does not correlate with objective measures of airway function or ventilation. Although clinical examination can also be an inaccurate predictor, useful clinical signs include labored breathing, tachycardia, pulsus paradoxus, prolonged expiration, and use of accessory muscles. Signs of a potentially fatal attack include central cyanosis and altered consciousness.

Arterial blood gas analysis provides objective assessment of maternal oxygenation, ventilation, and acid-base status. With this information, the severity of an acute attack can be assessed (see Fig. 51-1). That said, in a prospective evaluation, Wendel and associates (1996) found that routine arterial blood gas analysis did not help to manage most pregnant women who required admission for asthma control. If used, the results must be interpreted in relation to normal values for pregnancy. For example, a Pco2 > 35 mm Hg with a pH < 7.35 is consistent with hyperventilation and CO2 retention in a pregnant woman.

Pulmonary function testing should be routine in the management of chronic and acute asthma. Sequential measurement of the FEV1 or the peak expiratory flow rate—PEFR—are the best measures of severity. An FEV1 less than 1 L, or less than 20 percent of predicted value, correlates with severe disease defined by hypoxia, poor response to therapy, and a high relapse rate. The PEFR correlates well with the FEV1, and it can be measured reliably with inexpensive portable meters. Each woman determines her own baseline when asymptomatic—personal best—to compare with values when symptomatic. The PEFR does not change during the course of normal pregnancy (Brancazio, 1997).

Management of Chronic Asthma

Management of Chronic Asthma

The management guidelines of the Working Group on Asthma and Pregnancy include:

1. Patient education—general asthma management and its effect on pregnancy

2. Environmental precipitating factors—avoidance or control. Viral infections—including the common cold—are frequent triggering events (Murphy, 2013).

3. Objective assessment of pulmonary function and fetal well-being—monitor with PEFR or FEV1

4. Pharmacological therapy—in appropriate combinations and doses to provide baseline control and treat exacerbations. Compliance may be a problem, and periodic medication reviews are helpful (Sawicki, 2012).

In general, women with moderate to severe asthma should measure and record either their FEV1 or PEFR twice daily. The FEV1 ideally is > 80 percent of predicted. For PEFR, predicted values range from 380 to 550 L/min. Each woman has her own baseline value, and therapeutic adjustments can be made using this (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2012; Rey, 2007).

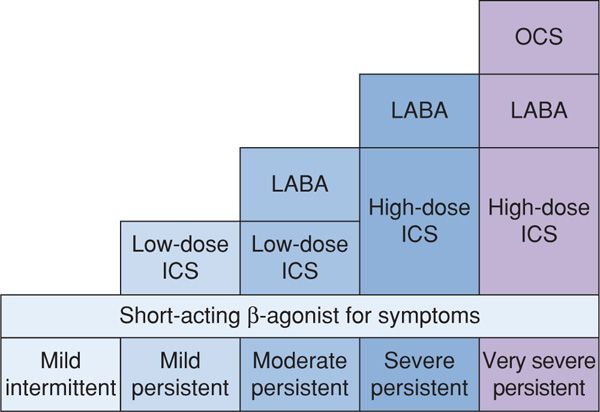

Treatment depends on disease severity. Although β-agonists help to abate bronchospasm, corticosteroids treat the inflammatory component. Regimens recommended for outpatient management are listed in Figure 51-2. For mild asthma, inhaled β-agonists as needed are usually sufficient. For persistent asthma, inhaled corticosteroids are administered every 3 to 4 hours. The goal is to reduce the use of β-agonists for symptomatic relief. A case-control study from Canada with a cohort of more than 15,600 nonpregnant women with asthma showed that inhaled corticosteroids reduced hospitalizations by 80 percent (Blais, 1998). And Wendel and colleagues (1996) achieved a 55-percent reduction in readmissions for severe exacerbations in pregnant asthmatics given maintenance inhaled corticosteroids along with β-agonist therapy.

FIGURE 51-2 Stepwise approach to asthma treatment. ICS = inhaled corticosteroids; LABA = long-acting β-agonists; OCS = oral corticosteroids. (Modified from Barnes, 2012.)

Theophylline is a methylxanthine, and its various salts are bronchodilators and possibly antiinflammatory agents. They have been used less frequently since inhaled corticosteroids became available. Some theophylline derivatives are considered useful for oral maintenance therapy if the initial response to inhaled corticosteroids and β-agonists is not optimal. Dombrowski and associates (2004b) conducted a randomized trial with nearly 400 pregnant women with moderate asthma. Oral theophylline was compared with inhaled beclomethasone for maintenance. In both groups, approximately 20 percent had exacerbations. Women taking theophylline had a significantly higher discontinuation rate because of side effects. Pregnancy outcomes were similar in the two groups.

Antileukotrienes inhibit leukotriene synthesis and include zileuton, zafirlukast, and montelukast. These drugs are given orally or by inhalation for prevention, but they are not effective for acute disease. For maintenance, they are used in conjunction with inhaled corticosteroids to allow minimal dosing. Approximately half of asthmatics will improve with these drugs (McFadden, 2005). They are not as effective as inhaled corticosteroids (Fanta, 2009). Finally, there is little experience with their use in pregnancy (Bakhireva, 2007).

Cromones include cromolyn and nedocromil, which inhibit mast cell degranulation. They are ineffective for acute asthma and are taken chronically for prevention. They are not as effective as inhaled corticosteroids and are used primarily to treat childhood asthma.

Management of Acute Asthma

Management of Acute Asthma

Treatment of acute asthma during pregnancy is similar to that for the nonpregnant asthmatic (Barnes, 2012). However, the threshold for hospitalization is significantly lowered. Intravenous hydration may help clear pulmonary secretions, and supplemental oxygen is given by mask. The therapeutic aim is to maintain the Po2 > 60 mm Hg, and preferably normal, along with 95-percent oxygen saturation. Baseline pulmonary function testing includes FEV1 or PEFR. Continuous pulse oximetry and electronic fetal monitoring, depending on gestational age, may provide useful information.

First-line therapy for acute asthma includes a β-adrenergic agonist, such as terbutaline, albuterol, isoetharine, epinephrine, isoproterenol, or metaproterenol, which is given subcutaneously, taken orally, or inhaled. These drugs bind to specific cell-surface receptors and activate adenylyl cyclase to increase intracellular cyclic AMP and modulate bronchial smooth muscle relaxation. Long-acting preparations are used for outpatient therapy.

If not previously given for maintenance, inhaled corticosteroids are commenced along with intensive β-agonist therapy. For severe exacerbations, magnesium sulfate may prove efficacious. Corticosteroids should be given early to all patients with severe acute asthma. Unless there is a timely response to bronchodilator and inhaled corticosteroid therapy, oral or parenteral corticosteroids are given (Lazarus, 2010). Intravenous methylprednisolone, 40 to 60 mg, every 6 hours for four doses is commonly used. Equipotent doses of hydrocortisone by infusion or prednisone orally can be given instead. Because their onset of action is several hours, corticosteroids are given initially along with β-agonists for acute asthma.

Further management depends on the response to therapy. If initial therapy with β-agonists is associated with improvement of FEV1 or PEFR to above 70 percent of baseline, then discharge can be considered. Some women may benefit from observation. Alternatively, for the woman with obvious respiratory distress, or if the FEV1 or PEFR is < 70 percent of predicted after three doses of β-agonist, admission is likely advisable (Lazarus, 2010). Intensive therapy includes inhaled β-agonists, intravenous corticosteroids, and close observation for worsening respiratory distress or fatigue in breathing (Wendel, 1996). The woman is cared for in the delivery unit or an intermediate or intensive care unit (ICU) (Dombrowski, 2006; Zeeman, 2003).

Status Asthmaticus and Respiratory Failure

Severe asthma of any type not responding after 30 to 60 minutes of intensive therapy is termed status asthmaticus. Braman and Kaemmerlen (1990) have shown that management of nonpregnant patients with status asthmaticus in an intensive care setting results in a good outcome in most cases. Consideration should be given to early intubation when maternal respiratory status worsens despite aggressive treatment (see Fig. 51-1). Fatigue, carbon dioxide retention, and hypoxemia are indications for mechanical ventilation. Lo and colleagues (2013) have described a woman with status asthmaticus in whom cesarean delivery was necessary to effect ventilation. Andrews (2013) cautioned that such clinical situations are uncommon.

Labor and Delivery

Labor and Delivery

For the laboring asthmatic, maintenance medications are continued through delivery. Stress-dose corticosteroids are administered to any woman given systemic corticosteroid therapy within the preceding 4 weeks. The usual dose is 100 mg of hydrocortisone given intravenously every 8 hours during labor and for 24 hours after delivery. The PEFR or FEV1 should be determined on admission, and serial measurements are taken if symptoms develop.

Oxytocin or prostaglandins E1 or E2 are used for cervical ripening and induction. A nonhistamine-releasing narcotic such as fentanyl may be preferable to meperidine for labor, and epidural analgesia is ideal. For surgical delivery, conduction analgesia is preferred because tracheal intubation can trigger severe bronchospasm. Postpartum hemorrhage is treated with oxytocin or prostaglandin E2. Prostaglandin F2αor ergotamine derivatives are contraindicated because they may cause significant bronchospasm.

ACUTE BRONCHITIS

Infection of the large airways is manifest by cough without pneumonitis. It is common in adults, especially in winter months. Infections are usually caused by viruses, and of these, influenza A and B, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial, coronavirus, adenovirus, and rhinovirus are frequent isolates (Wenzel, 2006). Bacterial agents causing community-acquired pneumonia are rarely implicated. The cough of acute bronchitis persists for 10 to 20 days (mean 18 days) and occasionally lasts for a month or longer. According to the 2006 guidelines of the American College of Chest Physicians, routine antibiotic treatment is not justified (Braman, 2006). Influenza bronchitis is managed as discussed below.

PNEUMONIA

According to Anand and Kollef (2009), current classification includes several types of pneumonia. Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is typically encountered in otherwise healthy young women, including during pregnancy. Health-care-associated pneumonia (HCAP) develops in patients in outpatient care facilities and more closely resembles hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP). Other types are nursing home-acquired pneumonia (NHAO) and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP).

Community-acquired pneumonia in pregnant women is relatively common and is caused by several bacterial or viral pathogens (Brito, 2011; Sheffield, 2009). Gazmararian and coworkers (2002) reported that pneumonia accounts for 4.2 percent of antepartum admissions for nonobstetrical complications. Pneumonia is also a frequent indication for postpartum readmission (Belfort, 2010). During influenza season, admission rates for respiratory illnesses double compared with rates in the remaining months (Cox, 2006). Mortality from pneumonia is infrequent in young women, but during pregnancy severe pneumonitis with appreciable loss of ventilatory capacity is not as well tolerated (Rogers, 2010). This generalization seems to hold true regardless of the pneumonia etiology. Hypoxemia and acidosis are also poorly tolerated by the fetus and frequently stimulate preterm labor after midpregnancy. Because many cases of pneumonia follow viral upper respiratory illnesses, worsening or persistence of symptoms may represent developing pneumonia. Any pregnant woman suspected of having pneumonia should undergo chest radiography.

Bacterial Pneumonia

Bacterial Pneumonia

Many bacteria that cause community-acquired pneumonia, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, are part of the normal resident flora (Bogaert, 2004). Some factors that perturb the symbiotic relationship between colonizing bacteria and mucosal phagocytic defenses include acquisition of a virulent strain or bacterial infections following a viral infection. Cigarette smoking and chronic bronchitis favor colonization with S pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Legionella species. Other risk factors include asthma, binge drinking, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (Goodnight, 2005; Sheffield, 2009).

Incidence and Causes

Pregnancy itself does not predispose to pneumonia. Jin and colleagues (2003) reported the antepartum hospitalization rate for pneumonia in Alberta, Canada, to be 1.5 per 1000 deliveries—almost identical to the rate of 1.47 per 1000 for nonpregnant women. Likewise, Yost and associates (2000) reported an incidence of 1.5 per 1000 for pneumonia complicating 75,000 pregnancies cared for at Parkland Hospital. More than half of adult pneumonias are bacterial, and S pneumoniae is the most common cause. Lim and coworkers (2001) studied 267 nonpregnant inpatients with pneumonia and identified a causative agent in 75 percent—S pneumoniae in 37 percent; influenza A, 14 percent; Chlamydophila pneumoniae, 10 percent; H influenzae, 5 percent; and Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Legionella pneumophila, 2 percent each. More recently, community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) has emerged as the second most common pathogen in nonpregnant adults (Moran, 2013). These staphylococci may cause necrotizing pneumonia (Mandell, 2012; Rotas, 2007).

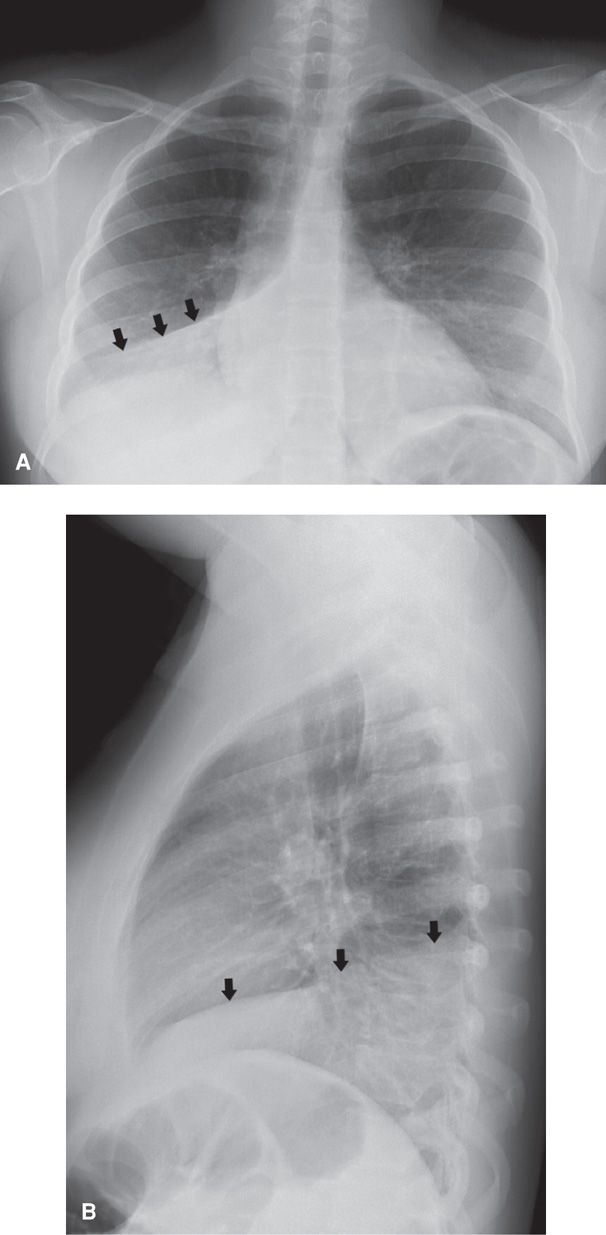

Diagnosis

Typical symptoms include cough, dyspnea, sputum production, and pleuritic chest pain. Mild upper respiratory symptoms and malaise usually precede these symptoms, and mild leukocytosis is usually present. Chest radiography is essential for diagnosis but does not accurately predict the etiology (Fig. 51-3). The responsible pathogen is identified in fewer than half of cases. According to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Thoracic Society (ATS), tests to identify a specific agent are optional. Thus, sputum cultures, serological testing, cold agglutinin identification, and tests for bacterial antigens are not recommended. At Parkland Hospital, the one exception to this is rapid serological testing for influenza A and B (Sheffield, 2009).

FIGURE 51-3 Chest radiographs in a pregnant woman with right lower lobe pneumonia. A. Complete opacification of the right lower lobe (arrows) is consistent with the clinical suspicion of pneumonia. B. Opacification (arrows) is also seen on the lateral projection.

Management

Although many otherwise healthy young adults can be safely treated as outpatients, at Parkland Hospital we hospitalize all pregnant women with radiographically proven pneumonia. For some, outpatient therapy or 23-hour observation is reasonable with optimal follow-up. Risk factors shown in Table 51-3 should prompt hospitalization.

TABLE 51-3. Criteria for Severe Community-Acquired Pneumoniaa

Respiratory rate ≥ 30/min

Pao2/Fio2 ratio ≤ 250

Multilobular infiltrates

Confusion/disorientation

Uremia

Leukopenia—WBC < 4000/μL

Thrombocytopenia—platelets < 100,000/μL

Hypothermia—core temperature < 36°C

Hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation

With severe disease, admission to an ICU or intermediate care unit is advisable. Approximately 20 percent of pregnant women admitted to Parkland Hospital for pneumonia require this level of care (Zeeman, 2003). Severe pneumonia is a relatively common cause of acute respiratory distress syndrome during pregnancy, and mechanical ventilation may become necessary. Indeed, of the 51 pregnant women who required mechanical ventilation in the review by Jenkins and coworkers (2003), 12 percent had pneumonia.

Antimicrobial treatment is empirical (Mandell, 2012). Because most adult pneumonias are caused by pneumococci, mycoplasma, or chlamydophila, monotherapy initially is with a macrolide—azithromycin, clarithromycin, or erythromycin. Yost and colleagues (2000) reported that erythromycin monotherapy, given intravenously and then orally, was effective in all but one of 99 pregnant women with uncomplicated pneumonia.

For women with severe disease according to criteria in Table 51-3, Mandell and associates (2007) summarized IDSA/ATS guidelines, which call for either: (1) a respiratory fluoroquinolone—levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, or gemifloxacin; or (2) a macrolide plus a β-lactam—high-dose amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate, which are preferred β-lactams. β-lactam alternatives include ceftriaxone, cefpodoxime, or cefuroxime. In areas in which there is “high-level” resistance of pneumococcal isolates to macrolides, these latter regimens are preferred. The teratogenicity risk of fluoroquinolones is low, and these should be given if indicated (Briggs, 2011). If community-acquired methicillin-resistant S aureus is suspected, then vancomycin or linezolid are added (Mandell, 2012; Sheffield, 2009). At this time, such therapy is empirical, and there are no tested regimens against CA-MRSA (Moran, 2013).

Clinical improvement is usually evident in 48 to 72 hours with resolution of fever in 2 to 4 days. Radiographic abnormalities may take up to 6 weeks to completely resolve (Torres, 2008). Worsening disease is a poor prognostic feature, and follow-up radiography is recommended if fever persists. Even with improvement, however, approximately 20 percent of women develop a pleural effusion. Pneumonia treatment is recommended for a minimum of 5 days. Treatment failure may occur in up to 15 percent of cases, and a wider antimicrobial regimen and more extensive diagnostic testing are warranted in these cases.

Pregnancy Outcome with Pneumonia

During the preantimicrobial era, as many as a third of pregnant women with pneumonia died (Finland, 1939). Although much improved, maternal and perinatal mortality rates both remain formidable. In five studies published after 1990, the maternal mortality rate was 0.8 percent of 632 women. Importantly, almost 7 percent of the women required intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Prematurely ruptured membranes and preterm delivery are frequent complications and have been reported in up to a third of cases (Getahun, 2007; Shariatzadeh, 2006). Likely related are older studies reporting a twofold increase in low-birthweight infants (Sheffield, 2009). In a more recent population-based study from Taiwan of nearly 219,000 births, there were significantly increased incidences of preterm and growth-restricted infants as well as preeclampsia and cesarean delivery (Chen, 2012).

Prevention

Pneumococcal vaccine is 60- to 70-percent protective against its 23 included serotypes. Its use has been shown to decrease emergence of drug-resistant pneumococci (Kyaw, 2006). The vaccine is not recommended for otherwise healthy pregnant women (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2013). It is recommended for those who are immunocompromised, including those with HIV infection; significant smoking history; diabetes; cardiac, pulmonary, or renal disease; and asplenia, such as with sickle-cell disease (Table 9-9, p. 185). Protection against pneumococcal infection in women with chronic diseases may be less efficacious than in healthy patients (Moberley, 2013).

Influenza Pneumonia

Influenza Pneumonia

Clinical Presentation

Influenza A and B are RNA viruses that cause respiratory infection, including pneumonitis. Influenza pneumonia can be serious, and it is epidemic in the winter months. The virus is spread by aerosolized droplets and quickly infects ciliated columnar epithelium, alveolar cells, mucus gland cells, and macrophages. Disease onset is 1 to 4 days following exposure (Longman, 2007). In most healthy adults, infection is self-limited.

Pneumonia is the most frequent complication of influenza, and it is difficult to distinguish from bacterial pneumonia. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010a), infected pregnant women are more likely to be hospitalized as well as admitted to an ICU. At Parkland Hospital during the 2003 to 2004 influenza season, pneumonia developed in 12 percent of pregnant women with influenza (Rogers, 2010). The 2009 influenza pandemic with the H1N1 strain was particularly severe. In a Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network study, 10 percent of pregnant or postpartum women admitted with H1N1 influenza were cared for in an ICU, and 11 percent of these ICU patients died (Varner, 2011). Risk factors included late pregnancy, smoking, and chronic hypertension. In California, 22 percent of H1N1-infected women required intensive care, and a third of these died.

Primary influenza pneumonitis is the most severe and is characterized by sparse sputum production and radiographic interstitial infiltrates. More commonly, secondary pneumonia develops from bacterial superinfection by streptococci or staphylococci after 2 to 3 days of initial clinical improvement. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2007b) reported several cases in which CA-MRSA caused influenza-associated pneumonitis with a case-fatality rate of 25 percent. Other possible adverse effects of influenza A and B on pregnancy outcome are discussed in Chapter 64 (p. 1241).

Management

Supportive treatment with antipyretics and bed rest is recommended for uncomplicated influenza. Early antiviral treatment has been shown to be effective (Jamieson, 2011). As discussed, influenza hospitalizations for those with advanced pregnancy are increased compared with nonpregnant women (Dodds, 2007; Schanzer, 2007). Rapid resistance of influenza A (H3N2) strains to amantadine or rimantadine in 2005 prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2006) to recommend against their use. Instead, neuraminidase inhibitors were given within 2 days of symptom onset for chemoprophylaxis and treatment of influenza A and B (Chap. 64, p. 1242). The drugs interfere with release of progeny virus from infected host cells and thus prevent infection of new host cells (Moscona, 2005). Oseltamivir is given orally, 75 mg twice daily, or zanamivir is given by inhalation, 10 mg twice daily. Recommended treatment duration with either is 5 days. The drugs shorten the course of illness by 1 to 2 days, and they may reduce the risk for pneumonitis (Jamieson, 2011). Our practice is to treat all pregnant women with influenza whether or not pneumonitis is identified. There are few data regarding use of these agents in pregnant women, but the drugs were not teratogenic in animal studies and are considered low risk (Briggs, 2011).

Other concerns for viral resistance are for avian H5N1 and H7N9 strains isolated in Southeast Asia. These are candidate viruses for an influenza pandemic with a projected mortality rate that exceeds 50 percent (Beigi, 2007; World Health Organization, 2008). Currently, international efforts are being made to produce a vaccine effective against both strains.

Preventively, vaccination for influenza A is recommended and is discussed in detail in Chapter 64 (p. 1242). Prenatal vaccination also affords protection for a third of infants for at least 6 months (Zaman, 2008). During the 2012–2013 flu season, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013b) reported that only half of pregnant women received the vaccine.

Varicella Pneumonia

Varicella Pneumonia

Infection with varicella-zoster virus—chicken pox—results in pneumonitis in 5 percent of pregnant women (Harger, 2002). Diagnosis and management are considered in Chapter 64 (p. 1240).

Fungal and Parasitic Pneumonia

Fungal and Parasitic Pneumonia

Pneumocystis Pneumonia

Fungal and parasitic pulmonary infections are usually of greatest consequence in immunocompromised hosts, especially in women with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Of these, lung infection with Pneumocystis jiroveci, formerly called Pneumocystis carinii, is a common complication in women with AIDS. The opportunistic fungus causes interstitial pneumonia characterized by dry cough, tachypnea, dyspnea, and diffuse radiographic infiltrates. Although this organism can be identified by sputum culture, bronchoscopy with lavage or biopsy may be necessary.

In a report from the AIDS Clinical Trials Centers, Stratton and colleagues (1992) described pneumocystis pneumonia as the most frequent HIV-related disorder in pregnant women. Ahmad and coworkers (2001) reviewed 22 cases during pregnancy and cited a 50-percent mortality rate. Treatment is with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or the more toxic pentamidine (Walzer, 2005). Experience with dapsone or atovaquone is limited. In some cases, tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation may be required.

As prophylaxis, several international health agencies recommend one double-strength trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole tablet orally daily for certain HIV-infected pregnant women. These include women with CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts < 200/μL, those whose CD4+ T lymphocytes constitute less than 14 percent, or if there is an AIDS-defining illness, particularly oropharyngeal candidiasis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013a; Forna, 2006).

Fungal Pneumonia

Any of a number of fungi can cause pneumonia. In pregnancy, this is usually seen in women with HIV infection or who are otherwise immunocompromised. Infection is usually mild and self-limited. It is characterized initially by cough and fever, and dissemination is infrequent.

Histoplasmosis and blastomycosis do not appear to be more common or more severe during pregnancy. Data concerning coccidioidomycosis are conflicting (Bercovitch, 2011; Patel, 2013). In a case-control study from an endemic area, Rosenstein and coworkers (2001) reported that pregnancy was a significant risk factor for disseminated disease. In another study, however, Caldwell and coworkers (2000) identified 32 serologically confirmed cases during pregnancy and documented dissemination in only three cases. Arsura (1998) and Caldwell (2000) and their associates reported that pregnant women with symptomatic infection had a better overall prognosis if there was associated erythema nodosum. Crum and Ballon-Landa (2006) reviewed 80 cases of coccidioidomycosis complicating pregnancy. Almost all women diagnosed in the third trimester had disseminated disease. Although the overall maternal mortality rate was 40 percent, it was only 20 percent for 29 cases reported since 1973. Spinello (2007) and Bercovitch (2011), with their associates, have provided reviews of coccidioidomycosis in pregnancy.

Most cases of cryptococcosis reported during pregnancy have been reported to manifest as meningitis. Ely and colleagues (1998) described four otherwise healthy pregnant women with cryptococcal pneumonia. Diagnosis is difficult because clinical presentation is similar to that of other community-acquired pneumonias.

The 2007 IDSA/ATS guidelines recommend itraconazole as preferred therapy for disseminated fungal infections (Mandell, 2007). Pregnant women have also been given intravenous amphotericin B or ketoconazole (Hooper, 2007; Paranyuk, 2006). Amphotericin B has been used extensively in pregnancy with no embryo-fetal effects. Because of evidence that fluconazole, itraconazole, and ketoconazole may be embryotoxic in large doses in early pregnancy, Briggs and associates (2011) recommend that first-trimester use should be avoided if possible.

Three echinocandin derivatives—caspofungin, micafungin, and anidulafungin—are effective for invasive candidiasis (Medical Letter, 2006; Reboli, 2007). They are embryotoxic and teratogenic in laboratory animals and use in human pregnancies has not been reported (Briggs, 2011).

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

This coronaviral respiratory infection was first identified in China in 2002, but no new cases have been reported since 2005. It caused atypical pneumonitis with a case-fatality rate of approximately 10 percent (Dolin, 2012). SARS in pregnancy had a case-fatality rate of up to 25 percent (Lam, 2004; Longman, 2007; Wong, 2004). Ng and coworkers (2006) reported that the placentas from 7 of 19 cases showed abnormal intervillous or subchorionic fibrin deposition in three, and extensive fetal thrombotic vasculopathy in two.

TUBERCULOSIS

Although tuberculosis is still a major worldwide concern, it is uncommon in the United States. The incidence of active tuberculosis in this country has plateaued since 2000 (Raviglione, 2012). More than half of active cases are in immigrants (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009b). Persons born in the United States have newly acquired infection, whereas foreign-born persons usually have reactivation of latent infection. In this country, tuberculosis is a disease of the elderly, the urban poor, minority groups—especially black Americans, and patients with HIV infection (Raviglione, 2012).

Infection is via inhalation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which incites a granulomatous pulmonary reaction. In more than 90 percent of patients, infection is contained and is dormant for long periods (Zumla, 2013). In some patients, especially those who are immunocompromised or who have other diseases, tuberculosis becomes reactivated to cause clinical disease. Manifestations usually include cough with minimal sputum production, low-grade fever, hemoptysis, and weight loss. Various infiltrative patterns are seen on chest radiograph, and there may be associated cavitation or mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Acid-fast bacilli are seen on stained smears of sputum in approximately two thirds of culture-positive patients. Forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis include lymphadenitis, pleural, genitourinary, skeletal, meningeal, gastrointestinal, and miliary or disseminated (Raviglione, 2012).

Treatment

Treatment

Cure rates with 6-month short-course directly observed therapy—DOT—approach 90 percent for new infections. Resistance to antituberculosis drugs was first manifest in the United States in the early 1990s following the epidemic from 1985 through 1992 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007a). Strains of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) increased rapidly as tuberculosis incidence fell during the 1990s. Because of this, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2003) now recommends a multidrug regimen for initial empirical treatment of patients with symptomatic tuberculosis. Isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol are given until susceptibility studies are performed. Other second-line drugs may need to be added. Drug susceptibility is performed on all first isolates.

In 2005, there was a worldwide emergence of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis—XDR-TB. This is defined as resistance in vitro to at least the first-line drugs isoniazid and rifampin as well as to three or more of the six main classes of second-line drugs—aminoglycosides, polypeptides, fluoroquinolones, thioamides, cycloserine, and para-aminosalicylic acid (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009a). Like their predecessor MDR-TB, these extensively resistant strains predominate in foreign-born persons (Tino, 2007).

Tuberculosis and Pregnancy

Tuberculosis and Pregnancy

The considerable influx of women into the United States from Asia, Africa, Mexico, and Central America has been accompanied by an increased frequency of tuberculosis in pregnant women. Sackoff and coworkers (2006) reported positive-tuberculin tests in half of 678 foreign-born women attending perinatal clinics in New York City. Almost 60 percent were newly diagnosed. Pillay and colleagues (2004) stress the prevalence of tuberculosis in HIV-positive pregnant women. Margono and coworkers (1994) reported that for two New York City hospitals, more than half of pregnant women with active tuberculosis were HIV positive. At Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami, Schulte and associates (2002) reported that 21 percent of 207 HIV-infected pregnant women had a positive skin test result. Recall also that silent endometrial tuberculosis can cause tubal infertility (Levison, 2010).

Without antituberculosis therapy, active tuberculosis appears to have adverse effects on pregnancy (Anderson, 1997; Mnyani, 2011). Contemporaneous experiences are few, however, because antitubercular therapy has diminished the frequency of severe disease. Outcomes are dependent on the site of infection and timing of diagnosis in relation to delivery. Jana and colleagues (1994) from India and Figueroa-Damian and Arrendondo-Garcia (1998) from Mexico City reported that active pulmonary tuberculosis was associated with increased incidences of preterm delivery, low-birthweight and growth-restricted infants, and perinatal mortality. From her review, Efferen (2007) cited twofold increased rates of low-birthweight and preterm infants as well as preeclampsia. The perinatal mortality rate was increased almost tenfold. Adverse outcomes correlate with late diagnosis, incomplete or irregular treatment, and advanced pulmonary lesions. From Taiwan, 761 pregnant women diagnosed with tuberculosis had a higher incidence of low-birthweight and growth-restricted infants (Lin, 2010).

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis is less common. Jana and coworkers (1999) reported outcomes in 33 pregnant women with renal, intestinal, and skeletal tuberculosis, and a third had low-birthweight newborns. Llewelyn and associates (2000) reported that nine of 13 pregnant women with extrapulmonary disease had delayed diagnoses. Prevost and Fung Kee Fung (1999) reviewed 56 cases of tuberculous meningitis in which a third of mothers died. Spinal tuberculosis may cause paraplegia, but vertebral fusion may prevent it from becoming permanent (Badve, 2011; Nanda, 2002). Other presentations include widespread intraperitoneal tuberculosis simulating ovarian carcinomatosis and degenerating leiomyoma, and hyperemesis gravidarum from tubercular meningitis (Kutlu, 2007; Moore, 2008; Sherer, 2005).

Diagnosis

There are two types of tests to detect latent or active tuberculosis. One is the time-honored tuberculin skin test (TST), and the others are interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs), which are becoming preferred (Horsburgh, 2011). IGRAs are blood tests that measure interferon-gamma release in response to antigens present in M tuberculosis, but not bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine (Ernst, 2007; Levison, 2010). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2005b, 2010b) recommend either skin testing or IGRA testing of pregnant women who are in any of the high-risk groups shown in Table 51-4. For those who received BCG vaccination, IGRA testing is used (Mazurek, 2010).

TABLE 51-4. Groups at High Risk for Having Latent Tuberculosis Infection

Health-care workers

Contact with infectious person(s)

Foreign-born

HIV-infected

Working or living in homeless shelters

Alcoholics

Illicit drug use

Detainees and prisoners

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree