Chapter 31 Puberty and Disorders of Pubertal development

This part of Essentials (Chapters 31 through 36) deals with the normal and abnormal hormonal influences on the female reproductive system. The sequence of events is an excellent example of the “Life-Course Perspective” for women’s health and health care introduced in Chapter 1. This series of events begins with endocrine changes in the fetus, the neonate, and then into childhood and pubertal development, then is followed by the early reproductive years, continuing on through the female climacteric, over the life course of a woman’s reproductive years. This section of the book concludes with a chapter on other common disorders that are influenced by normal and abnormal hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle.

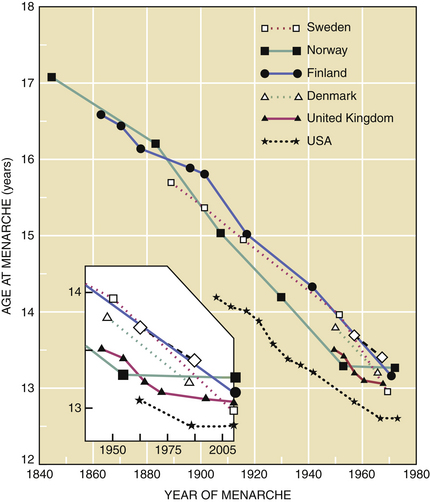

In the United States and Western Europe, a decrease in the age of menarche (age at first menses) was noted between 1840 and 1970. This trend has plateaued in the past 30 years (Figure 31-1). Presently, the mean age of menarche is about 12.4 years in the United States.

Endocrinologic Changes of Puberty

Endocrinologic Changes of Puberty

FETAL AND NEWBORN PERIOD

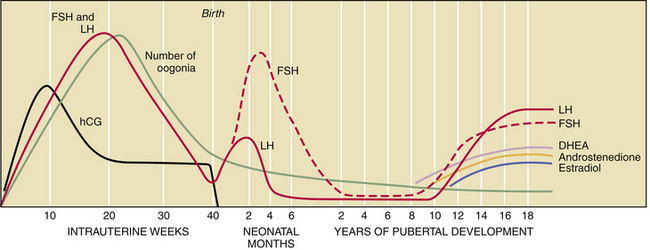

The fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis is capable of producing adult levels of gonadotropins and sex steroids. By 20 weeks’ gestation, levels of gonadotropins—follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH)—rise dramatically in both male and female fetuses (Figure 31-2). The female fetus acquires the lifetime peak number of oocytes by mid-gestation, and she experiences a brief period of follicular maturation and sex steroid production in response to elevated gonadotropin levels in utero. This transient increase in serum estradiol (a sex steroid) acts on the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary unit, resulting in a reduction of gonadotropin secretion (negative feedback effect), which in turn reduces estradiol production. This indicates that the inhibitory effect of sex steroids on gonadotropin release is operative before birth.

PUBERTAL ONSET

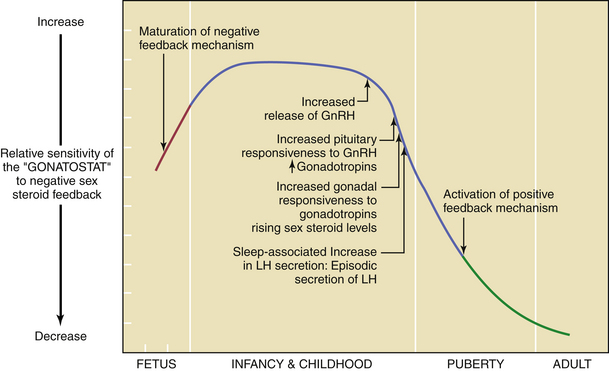

By about the 11th year of life, there is a gradual loss of sensitivity by the gonadostat to the negative feedback of sex steroids (Figure 31-3). As a consequence of this reduced negative feedback effect, GnRH pulses (with their mirroring pulses of FSH and LH) increase in amplitude and frequency. The factors that reduce the sensitivity of the gonadostat are incompletely understood. Some studies indicate that a rise in the concentration of leptin, a hormone produced by adipocytes (fat cells) that mediates appetite satiety, precedes and is necessary for this change. This, in turn, supports the connection between minimum weight or total body fat and the onset of puberty. A further decrease in sensitivity of the gonadostat, combined with the loss of intrinsic central nervous system inhibition of hypothalamic GnRH release, is heralded by sleep-associated increases in GnRH secretion. This nocturnal-dominant pattern gradually shifts into an adult-type secretory pattern, with GnRH pulses occurring every 90 to 120 minutes throughout the 24-hour day.

Somatic Changes of Puberty

Somatic Changes of Puberty

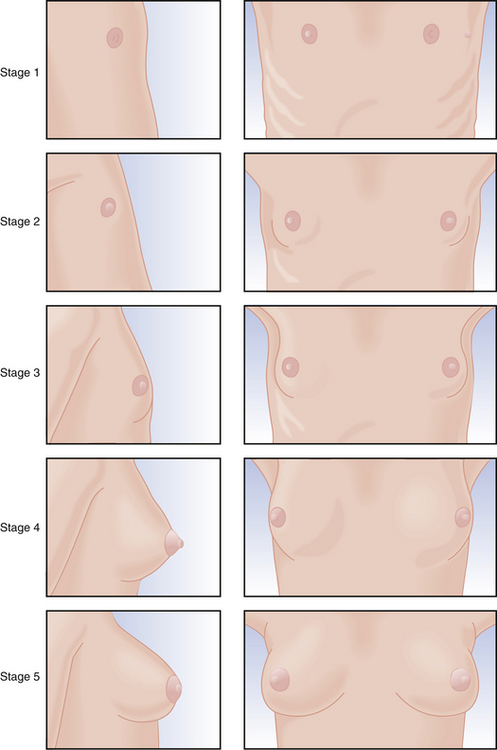

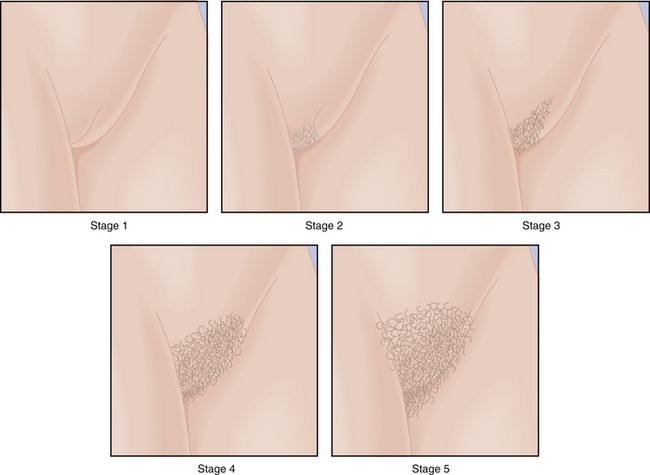

Physical changes of puberty involve the development of secondary sexual characteristics and the acceleration of linear growth (gain in height). The classification of breast and pubic hair development by Marshall and Tanner is employed for descriptive and diagnostic purposes (Figures 31-4 and 31-5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree