67 Puberty

Etiology And Pathogenesis

Hormonal Changes of Puberty

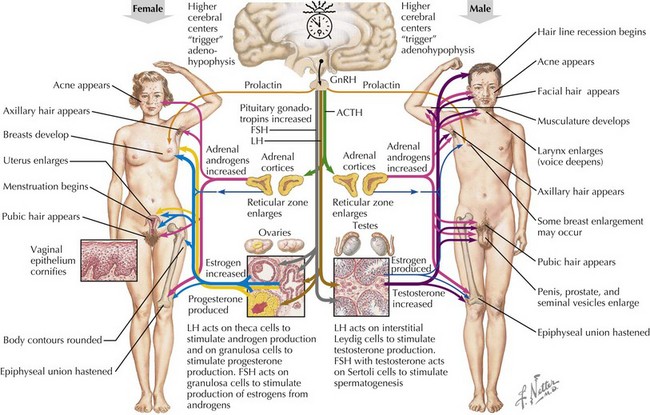

Pubertal onset is initiated by reactivation of hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion (Figure 67-1). The hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis is active during fetal development and the first few months of life but is suppressed in infancy by neural input to the arcuate nucleus and remains so throughout childhood (juvenile pause). The transition from a quiescent state toward puberty involves gradually increasing, pulsatile release of GnRH by the hypothalamus, which leads to pituitary release of gonadotropins, first luteinizing hormone (LH) and then follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). An increased amplitude and frequency of LH pulses during the night are the first detectable hormonal changes at the onset of puberty. Gonadotropins induce gonadal growth and maturation (gonadarche), marked by increasing production of sex steroids, mainly testosterone and estradiol. Apart from the increase in size of the testes, nearly all of the physical changes of puberty result from increasing levels of androgens and estrogens (Table 67-1).

Table 67-1 Physical Effects of Sex Hormones

| Hormone Effect | Androgen Effects | Estrogen Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Early | Pubic hair development (stage 2-3) Acne Body odor | Breast development Growth acceleration |

| Moderate | Full pubic hair development Early axillary hair and facial hair (upper lip) Growth acceleration Penile enlargement | Uterine enlargement Endometrial thickening Vaginal mucosa dulls (pink) Physiologic leukorrhea |

| Advanced | Voice changes Increased muscle mass Broadening of shoulders Widening of jaw Full facial hair Growth acceleration | Menses Fat redistribution Pelvic widening |

Normal Pubertal Timing

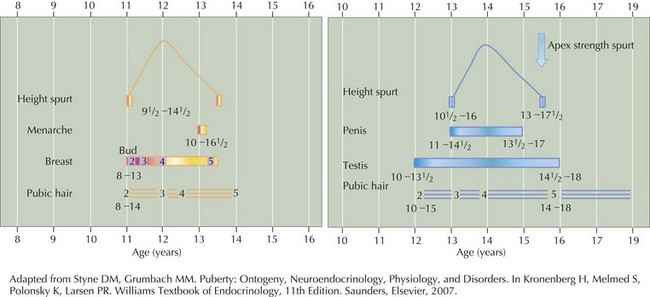

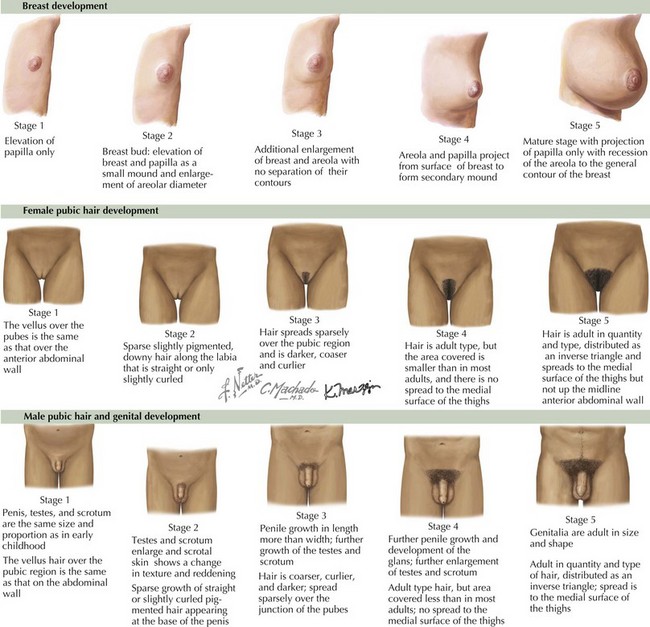

Although the age of onset may vary, the stages of puberty and their durations tend to be fairly constant (Figure 67-2). The most widely used system for describing the stages of puberty is the modified Tanner system (Figure 67-3), by which girls are assessed using the stage of breast development and pubic hair and boys by genitalia, pubic hair, and testicular volumes. The temptation to describe children with “unitary Tanner stages” should be resisted because it discourages recognition of important discordances that may indicate disease.

Differential Diagnosis

Premature Sex Hormone Effects

Traditionally, early sex hormone effects have been classified as central, peripheral, or incomplete (Box 67-1). Central puberty reflects activation of the entire HPG axis, and the physical changes are typically those of normal puberty for a child of that sex. In contrast, peripheral sex hormone sources include adrenal and gonadal disorders, abdominal or pelvic tumors, or exogenous sex steroids. Physical changes reflect the predominant excess hormones (androgenic or estrogenic) and are often markedly discordant from normal pubertal development. Incomplete puberty describes early physical changes that do not have a pathologic source but do not progress to full development at the usual tempo.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree