26 Psychological Symptoms

As I stand in the night the fear approaches

I stand strong and face it with all I have

I stand my ground and face whatever it comes at me with

It reaches to the darkest part of my soul

It flows through me and never seems to go away

For the hopes of the end and of something better

I stand strong for the things that help me fight it

In the end it does not end but I still stand strong

Into the night I stand bold till the end

But then there is another journey ahead

I will face sadness, humiliation, opinion, pain, disgrace, and choice as they tear me apart.

The medicine from friendship, family, love, and life experiences heal me.

—Derick Mount, whose osteosarcoma was diagnosed at age 12. (12/3/1986–8/17/2005)

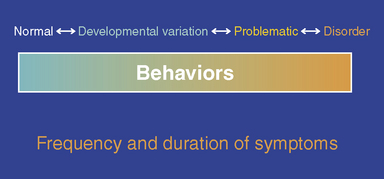

Symptoms such as anxiety and depressed mood are evaluated on a continuum (Fig. 26-1). In general, increasing frequency of a symptom, lasting longer than two continuous weeks, and the presence of significant impairment in functioning or the expressed desire for death should alert clinicians to pursue an in-depth mental health assessment to explore the need for specific psychological intervention. Such assessments must take into account the cultural background of the family, because psychological symptoms may be either minimized or emphasized in certain cultural contexts.1

Anxiety in Pediatric Patients

Anxiety is thought to be problematic when its intensity and duration begin to affect functioning and quality of life, especially in the context of childhood cancer or other life-threatening illness. It can develop as a primary disorder, as a psychological reaction to illness, as a secondary disorder, or may be comorbid with other psychiatric disorders such as depression (Table 26-1). Anxiety may be acute or chronic. It is important to identify any underlying treatable medical etiologies for new onset anxiety (Box 26-1). For example, akathesia, a common side effect of medications, may be misdiagnosed as anxiety.

TABLE 26-1 Anxiety Disorders Seen in Medically Ill Children

| Diagnosis | Key symptoms and/or considerations |

|---|---|

| Generalized anxiety disorder | Excessive worry with associated restlessness, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, sleep disturbance |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | Obsessive preoccupation or fears about physical illness |

| Acute Stress/ post-traumatic stress disorder | Numbness, intrusiveness and hyperarousal; diagnosis depends on duration greater than one month; can occur as a reaction to hearing diagnosis, aspects of medical treatment, or memories of treatment; common in chronic physical illness |

| Separation anxiety disorder | Inappropriate and/or excessive worry about separation from home and/or the family; common in children younger than age 6, resurgence around age 12 |

| Phobias | Specific fear of blood and/or needle, claustrophobia, agoraphobia, white coat syndrome; may lead to difficulty with MRI scans, confinement in isolation, treatment compliance, etc. |

| Panic disorder | Severe palpitations, diaphoresis, and nausea; feeling of impending doom; resulting panic attacks lasting at least several minutes |

| Anxiety disorder caused by general medical condition | Should be considered if history is not consistent with symptoms of primary anxiety disorder/is resistant to treatment; more likely if physical symptoms such as shortness of breath, tachycardia, or tremor are pronounced |

| Substance-induced anxiety disorder | May result from direct effect of substance or withdrawal; particular awareness to medication history, start of new medication, change in dosage |

Adapted and reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR).

BOX 26-1 Possible Medical Conditions Precipitating Anxiety in Medically lll Patients

Adapted and reprinted with permission from the Clinical Manual of Pediatric Psychosomatic Medicine.

2006 American Psychiatric Association.

Anxiety disorders are common in the general population in the United States, with the prevalence of any lifetime anxiety disorder estimated to be 28.8%, with 11 years as the median age of onset.2 Age of onset varies for particular anxiety disorders, with a median onset at 7 years for separation anxiety and phobia disorders, at 13 years for social phobias, and at 19 to 31 years for other disorders. Anxiety is common in children, with a lifetime prevalence of any anxiety disorder at 15% to 20%.3 In children with chronic illness, an estimated 20% to 35 % have an anxiety disorder. In a study assessing anxiety in pediatric oncology patients, 14.3% of 63 children met diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder.4 The prevalence of anxiety in other disorders, such as asthma, ranges from 9%5 to 37%,6 while in diabetes anxiety symptoms range from 0.8%7 to almost 20%. One study found anxiety symptoms persisting 10 years after diagnosis of diabetes.8 High rates of anxiety, up to 63%, have been reported in children with epilepsy.9 Clearly, age at onset, sample selection, method and timing of ascertainment of anxiety disorders need to be considered when interpreting the literature on anxiety disorders in chronically ill children.

Post-traumatic stress has emerged as a possible model for understanding cancer-related distress across family members during the illness and beyond.10 Pediatric medical traumatic stress is a set of psychological and physiological responses of children and their families to pain, injury, serious illness, medical procedures, and invasive or frightening treatment experiences. Traumatic stress responses include symptoms of arousal, re-experiencing, and avoidance or a constellation of these symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or acute stress disorder.11 Traumatic stress responses are more related to one’s subjective experience of the medical event than its objective severity and are seen in children as well as in parents across the course of treatment and into survivorship.12 Anticipatory anxiety can develop initially or during the course of treatment and clinicians need to monitor vigilantly for increased irritability, resistance, and outright refusal to cooperate with procedures. Many clinicians have found providing anticipatory guidance about normative psychological symptoms, including anxiety and worry about tests, procedures, and hospitalizations, to children and their parents is helpful in decreasing the stress of uncertainty.

Evaluation of anxiety in a pediatric setting

Assessment by a palliative care team member for anxiety begins with a careful medical history including the current subjective symptoms to rule out possible medical conditions precipitating anxiety, such as the use of drugs or alcohol (see Box 26-1). It is critical to evaluate for pain because pain can affect mood and anxiety (see Chapter 22). It is also imperative to ask if the child has a history of anxiety disorders, current or previous use of prescribed medications, or a family history of psychiatric disorders, especially anxiety or mood disorders. It is important to learn about previous anxiety and coping around the initial diagnosis; anxiety surrounding hospitalizations; fear of needles and/or procedures; anticipatory anxiety; or the physical effects of illness. Be specific as to whether there are rooms, people, sights, times during the day, days of the week, sounds or smells that the child finds aversive in order to better understand how to modify these factors. The clinician should be alert to previous difficulties with separation from home and/or other familiar settings or people. Worries about death or dying need to be explicitly questioned, using developmentally appropriate language. Assessment of sources of anxiety such as academic and social impact and financial burden of illness may add important information.

A thorough assessment for an anxiety disorder includes a review of:

Depression in Pediatric Patients

Depression describes transient sad feelings in combination with a sustained low mood leading to impairment in overall functioning and may present with both psychological and physical symptoms. In general, the most prominent symptoms of depression are sadness, dysphoria, and anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure). Depression may exist as a primary disorder, as a psychological reaction to illness, as a secondary disorder to an organic etiology, or may be comorbid with other psychiatric disorders such as anxiety (Table 26-2). Even if patients do not meet diagnostic criteria for a depressive disorder, they should still receive appropriate clinical follow-up and continued monitoring.

TABLE 26-2 Depressive Disorders Seen in Medically Ill Children

| Diagnosis | Key symptoms and/or considerations |

|---|---|

| Major depressive episode | Primary mood disorder most often associated with previous psychiatric history. Must exhibit at least 5 symptoms for at least 2 weeks of: persistent depressed mood, anhedonia, irritability, change of weight, change of appetite, sleep disturbance, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness and/or guilt, diminished ability to concentrate, recurrent thoughts of death. |

| Dysthymia | Chronically depressed or irritable mood for at least 1 year that is less disabling than MDD. At least 2 symptoms of: sleep disturbance, fatigue, diminished ability to concentrate, feelings of hopelessness. |

| Adjustment disorder (that is, the adjustment to diagnosis, course, and treatment of illness) | Depressed mood in reaction to medical illness; the most common mood disorder in cancer patients. Symptoms of depression do not meet criteria for major depression but are associated with mildly impaired functioning or shorter duration. |

| Mood disorder caused by general medical condition | Depressed mood, elevated mood, or irritability caused by underlying medical condition; may be one of first symptoms of medical illness. Relationship to significant physical examination and study findings; particular attention to any central nervous system (CNS) lesions in frontal, limbic, and temporal lobes as possible cause. |

| Substance-induced mood disorder | Depression induced by medication, drugs, or alcohol. Usually resolves within 2 weeks of abstinence. Important to note the course of depression in initiation and/or dosage of a medicine (for example, high-dose α interferon). |

| Primary or secondary mania | Manic symptoms as a primary disorder, secondary to medical condition, induced by medication (such as corticosteroids) or toxicity. Symptoms include abnormally elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, rapid speech. Patients with brain atrophy or sleep deprivation are more prone. |

| Behavioral considerations | Regression: When stress of illness leads to behavioral regression and manifests as clinginess, social withdrawal, tearfulness, depressed mood. Very common in children and adolescents. Generally resolves after illness and/or hospitalization. |

| Bereavement | Fleeting thoughts of sadness or suicide that are part of normal mourning process. Complicated bereavement, prolonged and more persistent symptoms of mourning, needs to be distinguished from depression. |

Adapted and reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR).

The lifetime prevalence of a major depressive disorder in the general population in the United States is 16.6%. Approximately 2% of school age children and 4% to 8% of adolescents meet criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) with gender differences becoming more apparent with age (females greater than males).2 A meta-analysis estimates a 9% prevalence of depression in chronically ill children and some studies show a lower-than-normal rate of depression in pediatric cancer.13 Generally, studies using clinical interview methodologies, rather than self report, tend to report higher levels of depression. Some large samples have shown no difference in the prevalence of depression in children with other conditions such as asthma,6 while others14 found that 16.3% of youths with asthma compared with 8.6% of youths without asthma met DSM-IV criteria for one or more anxiety or depressive disorders. The prevalence of depression in youth with diabetes is believed to be two to three times greater than in those without diabetes.15 A study8 found that in the 10 years of post-diabetes diagnosis, 27% of the children and adolescents developed depression. Children with complex partial seizures and absence epilepsy are five times more likely to have a mood or anxiety disorder than healthy children.9 Depression, although common, is often unrecognized and untreated in children and adolescents with epilepsy.16 These data taken across chronic illnesses suggest that screening at regular intervals for depression and anxiety should be considered in chronically ill children, but rates may vary with the particular disease group.

At terminal stages of an illness, clinicians can help the child and family work through feelings of loss and should recognize symptoms of depression as part of the grieving process. Whenever possible, it is important to find ways to help children communicate their worries to family or the clinical team, so that the diagnosis of depression or anxiety can be properly made or ruled out. For example, emotional withdrawal should not be confused with depression. Emotional distancing provides the opportunity to conserve energy to focus on a few significant relationships rather than dealing with multiple painful separations.17 In addition, chronic and severe pain is exhausting, and once under control, the child’s distress may improve. Therefore, it is essential that the palliative care team assess for the role that pain and withdrawal might have in depressive symptoms. Yet, as psychiatric symptoms can be reactive to the stresses and disruptions being experienced, a good history that includes knowledge of these conditions can help the palliative care team anticipate problems and provide them with the time to engage additional resources as needed.

One of the most frequent reasons for a psychiatric consult in a pediatric hospital setting is depression, especially within one year of a cancer diagnosis. Pediatric oncologists in the United States commonly prescribe antidepressants. A survey of 40 pediatric oncologists found that half had prescribed a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)18 while a review of a children’s hospital reported that 10% of pediatric oncology patients received an antidepressant medication within one year of diagnosis.19 On admission to the NIH Clinical Center, 14% of pediatric oncology patients had been prescribed a psychotropic medication.20 These clinicians appear to be responding to significant distress associated with medical illness and its treatments.

Evaluation of depression in a pediatric setting

Assessment for depression in a child begins with a careful medical history including the current subjective symptoms to rule out possible medical conditions precipitating depression, such as use of drugs or alcohol (Box 26-2; see also Box 26-1). It is critical to evaluate for pain, as significant pain can affect mood and anxiety (see Chapter 22). It is also imperative to ask if the child has a history of mood disorders, previous suicide attempts, current or previous use of prescribed medications, or a family history of psychiatric disorders, especially suicidal behavior. It is useful to elicit a history of prior losses, including serious illness and/or death of family members, parental divorce, loss of pet, disappointments in school or social relationships, and how the child has, until this point, coped with his or her illness.

BOX 26-2 Additional Considerations for Medical Conditions Precipitating Depression in Medically lll Patients

Adapted and reprinted with permission from Abraham J, Gulley JL, Allegra CJ, editors: The Bethesda Handbook of Clinical Oncology, Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2005.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree