The Puerperium

The puerperium is a particularly stressful time and carries as increased risk for mental illness. Up to 15 percent of women develop a nonpsychotic postpartum depressive disorder within 6 months of delivery (Tam, 2007; Yonkers, 2011). A few have a more severe, psychotic illness following delivery, and half of these have a bipolar disorder (Yonkers, 2011). Depressive disorders are more likely in women with obstetrical complications such as severe preeclampsia or fetal-growth restriction, especially if associated with early delivery. However, among women with a history of bipolar disorder, these factors do not seem to play as great a role in the development of mania or depression (Yonkers, 2011).

Maternity Blues

Also called postpartum blues, this is a time-limited period of heightened emotional reactivity experienced by half of women within approximately the first week after parturition. Prevalence estimates for the blues range from 26 to 84 percent depending on criteria used for diagnosis (O’Hara, 2014). This emotional state generally peaks on the fourth or fifth postpartum day and normalizes by day 10 (O’Keane, 2011). The predominant mood is happiness. However, affected mothers are more emotionally labile, and insomnia, weepiness, depression, anxiety, poor concentration, irritability, and affective lability may be noted. Mothers may be transiently tearful for several hours and then recover completely, only to be tearful again the next day. Supportive treatment is indicated, and sufferers can be reassured that the dysphoria is transient and most likely due to biochemical changes. They should be monitored for development of depression and other severe psychiatric disturbances.

Prenatal Evaluation

Prenatal Evaluation

Screening for mental illness is generally done at the first prenatal visit. Factors include a search for psychiatric disorders, including hospitalizations, outpatient care, prior or current use of psychoactive medications, and current symptoms. Risk factors should be evaluated—for example, a prior personal or family history of depression conveys a significant risk for depression. Women with a history of sexual, physical, or verbal abuse; substance abuse; and personality disorders are also at greater risk for depression (Akman, 2007; Tam, 2007). Smoking and nicotine dependence have been associated with an increase in rates of all mental disorders in pregnancy (Goodwin, 2007). Finally, because eating disorders may be exacerbated by pregnancy, affected women should be followed closely.

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2012a), there is currently insufficient evidence to make a firm recommendation for routine depression screening, either during or after pregnancy. At Parkland Hospital, all women are asked about depression and domestic violence at their first prenatal visit. They are also screened again during their first postpartum visit using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). In an analysis of more than 17,000 of these questionnaires, 6 percent had scores that indicated either minor or major depressive symptoms. Twelve of these 1106 women also had thoughts of self-harm (Nelson, 2013).

Treatment Considerations

Treatment Considerations

A large number of psychotropic medications may be used for management of the myriad mental disorders encountered in pregnancy. For treatment options that include psychosocial and psychological interventions, treatment decisions are ideally shared between patients and their health-care providers. Women taking psychotropic medication should be informed of likely side effects. Many of these drugs are discussed in Chapter 12 as well as by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2012b). Additionally, these drugs are discussed subsequently in this chapter. Babbitt (2014) and Pozzi (2014) and their colleagues have recently reviewed principles of antenatal and intrapartum care of women with major mental disorders.

Pregnancy Outcomes

Pregnancy Outcomes

There are only a few reports of psychiatric disorders and pregnancy outcomes. Some, but not all, link maternal psychiatric illness with untoward outcomes such as preterm birth, low birthweight, and perinatal mortality (Schneid-Kofman, 2008; Steinberg, 2014; Yonkers, 2009). In a population-based cohort of more than 500,000 California births, Kelly and colleagues (2002) assessed the perinatal effects of a psychiatric diagnosis that included all International Classification of Diseases 9th Edition Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic codes. Women with these diagnoses had up to a threefold increased incidence of a very-low- or low-birthweight neonate or preterm delivery. In another study of more than 1100 women enrolled in a Healthy Start initiative, women with depression were found to be 1.5 times more likely to be delivered early compared with nondepressed women. Conversely, Littleton and associates (2007) reviewed 50 studies and concluded that anxiety symptoms—a common comorbidity in depression—had no adverse effect on outcomes.

CLASSIFICATION OF MENTAL DISORDERS

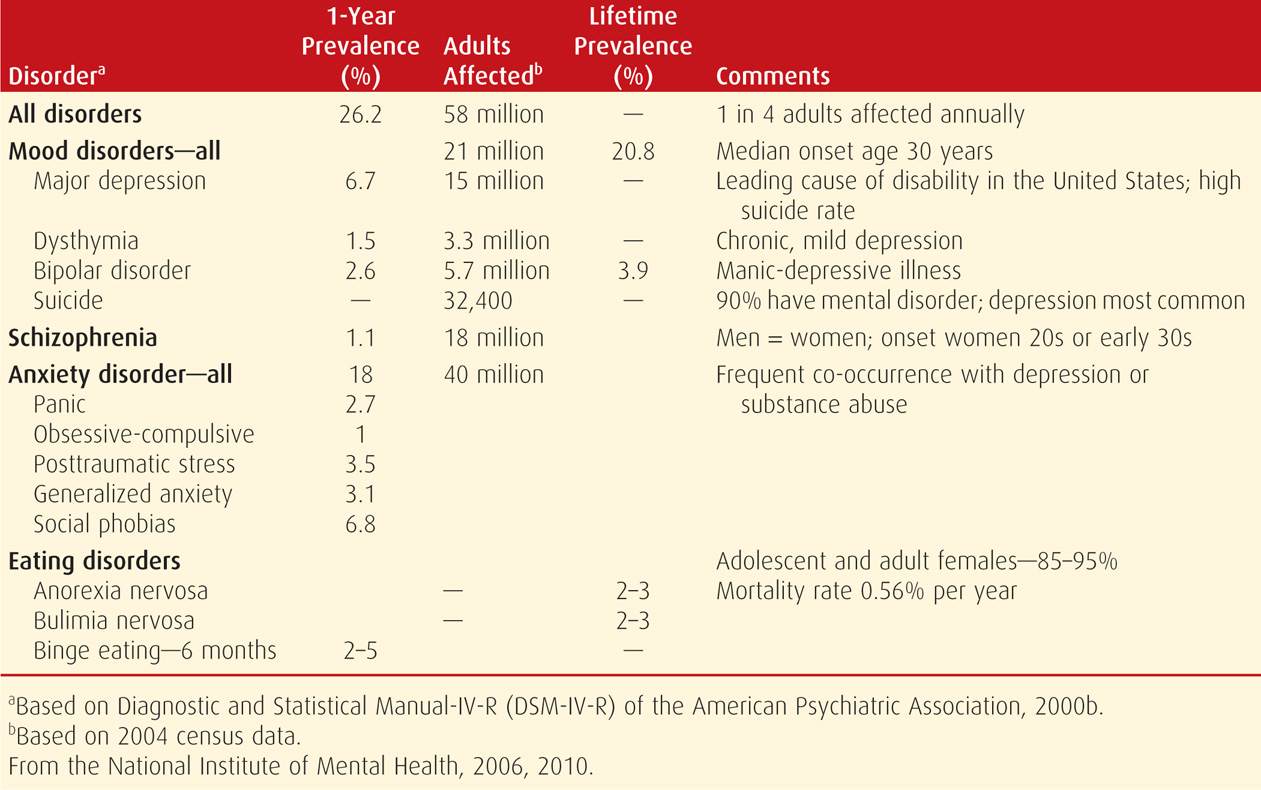

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-V is the most recent version by the American Psychiatric Association (2013). Its purpose is to assist in the classification of mental disorders, and it specifies criteria for each diagnosis. Shown in Table 61-1 are 12-month prevalences of mental disorders for adults.

TABLE 61-1. The 12-Month Prevalence of Mental Disorders in Adults in the United States

Depressive Disorders

Depressive Disorders

According to the National Institute of Mental Health (2010), the lifetime prevalence of depressive disorders in the United States is 21 percent. Women are 50 percent more likely than men to experience a major mood disorder during their lifetime. Historically, these include major depression—a unipolar disorder—and manic-depression—a bipolar disorder with both manic and depressive episodes. It also includes dysthymia, which is chronic, mild depression. When concurrent with medical complications such as diabetes, heart disease, and asthma, major mood disorders worsen medical outcomes, and as a group, contribute to two thirds of all suicides (Yonkers, 2011).

Major Depression

Major Depression

This is the most common depressive disorder, and an estimated 12 million women each year in the United States are affected (Mental Health America, 2013a). The lifetime prevalence is 17 percent, but only half ever seek care. The diagnosis is arrived at by identifying symptoms listed in Table 61-2.

TABLE 61-2. Symptoms of Depressive Illnessa

Persistent sad, anxious, or “empty” feelings

Feelings of hopelessness and/or pessimism

Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, and/or helplessness

Irritability, restlessness

Loss of interest in activities or hobbies once pleasurable, including sex

Fatigue and decreased energy

Difficulty concentrating, remembering detail, and making decisions

Insomnia, early-morning wakefulness, or excessive sleeping

Overeating or appetite loss

Thoughts of suicide, suicide attempts

Persistent aches or pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems that do not ease even with treatment

Major depression is multifactorial and prompted by genetic and environmental factors. First-degree relatives have a 25-percent risk, and female relatives are at even higher risk. One genome-wide linkage analysis of more than 1200 mothers suggests that variation in chromosomes 1 and 9 increases susceptibility to postpartum mood symptoms (Mahon, 2009). Families of affected individuals also often have members with alcohol abuse and anxiety disorders. Provocative conditions leading to depression include life events that prompt grief reactions, substance abuse, use of certain medications, and other medical disorders. Although life events can trigger depression, genes influence the response to life events, making the distinction between genetic and environmental factors difficult.

Pregnancy

It is unquestionable that pregnancy is a major life stressor that can precipitate or exacerbate depressive tendencies. In addition, there are likely various pregnancy-induced effects. Hormones certainly affect mood as evidenced by premenstrual syndrome and menopausal depression. Estrogen has been implicated in increased serotonin synthesis, decreased serotonin breakdown, and serotonin receptor modulation (Deecher, 2008). Concordantly, women who experience postpartum depression often have higher predelivery serum estrogen and progesterone levels and experience a greater decline postpartum (Ahokas, 1999).

Dennis and associates (2007) queried the Cochrane Database and reported the prevalence of antenatal depression to average 11 percent. Melville and coworkers (2010) found it in nearly 10 percent of more than 1800 women enrolled for prenatal care at a single university obstetrical clinic. Others have reported the incidence to be much higher (Lee, 2007; Westdahl, 2007). In another report, Luke and colleagues (2009) found major depressive symptoms in 25 percent of pregnant African American women. Hayes and associates (2012) reported that 13 percent of pregnant women in the Tennessee Medicaid program filled an antidepressant prescription either before or during pregnancy. In another report of almost 119,000 pregnancies in seven health plans, Andrade and coworkers (2008) found that only 6.6 percent received antidepressants at any time during pregnancy. These findings support to the notion that only half of pregnant women with depression receive treatment.

Postpartum depression—major or minor—develops in 10 to 20 percent of parturients (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008; Mental Health America, 2013b). Available data indicate that unipolar major depression may be slightly more prevalent during the puerperium than among women in the general population (Yonkers, 2011). In addition to antenatal depression, postpartum depression has been associated with young maternal age, unmarried status, smoking or drinking, substance abuse, hyperemesis gravidarum, preterm birth, and high utilization of sick leave during pregnancy (Endres, 2013; Lee, 2007; Marcus, 2009).

Depression is frequently recurrent. At least 60 percent of women taking antidepressant medication before pregnancy have symptoms during pregnancy. According to Hayes and colleagues (2012), approximately three fourths of women taking antidepressants before pregnancy stopped taking them before or during the first trimester. For those who discontinue treatment, almost 70 percent have a relapse compared with 25 percent who continue therapy. Up to 70 percent of women with previous postpartum depression have a subsequent episode. Women with both prior puerperal depression and a current episode of “maternity blues” are at inordinately high risk for major depression. Indeed, the need for postpartum depression help was the fourth most common challenge identified at 2 to 9 months postpartum by the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System—PRAMS (Kanotra, 2007).

Postpartum depression is generally underrecognized and undertreated. Major depression during pregnancy or after delivery can have devastating consequences for affected women, their children, and families. Among new mothers, one of the most significant contributions to their mortality rate is suicide, which is most common among women with mental illness (Koren, 2012; Palladino, 2011). If left untreated, up to 25 percent of women with postpartum depression will be depressed 1 year later. As the duration of depression increases, so too do the number of sequelae and their severity. In addition, maternal depression during the first weeks and months after delivery can lead to insecure attachment and later behavioral problems in the child.

Treatment

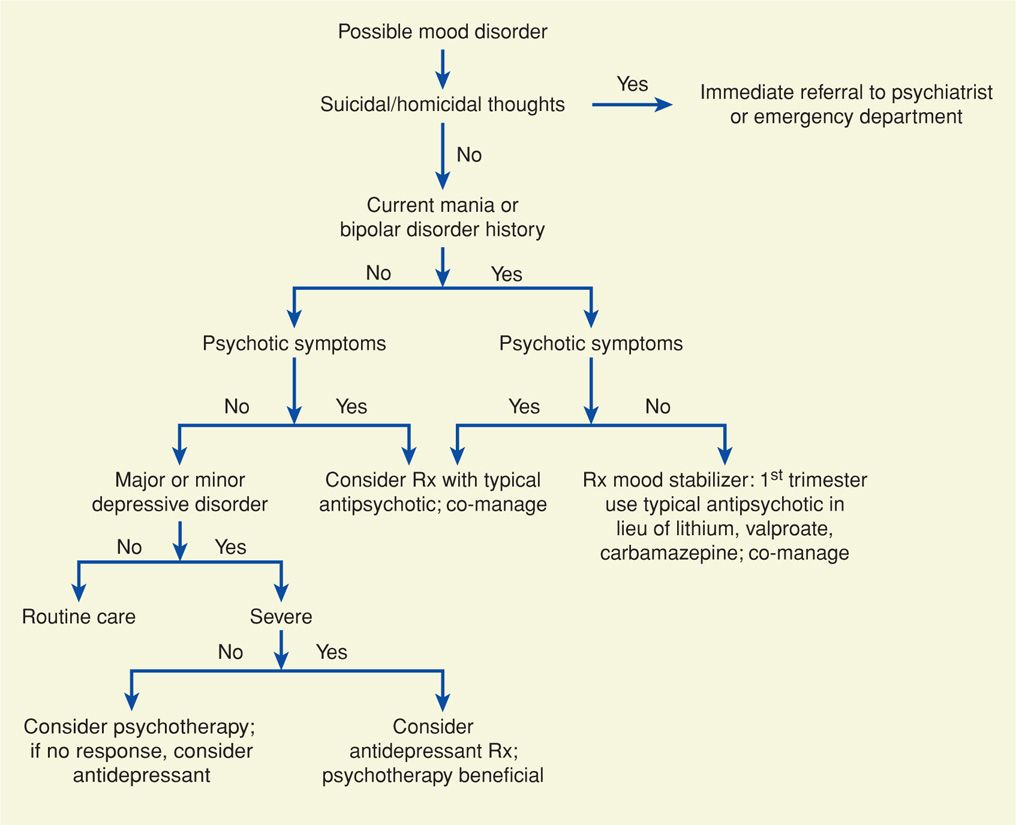

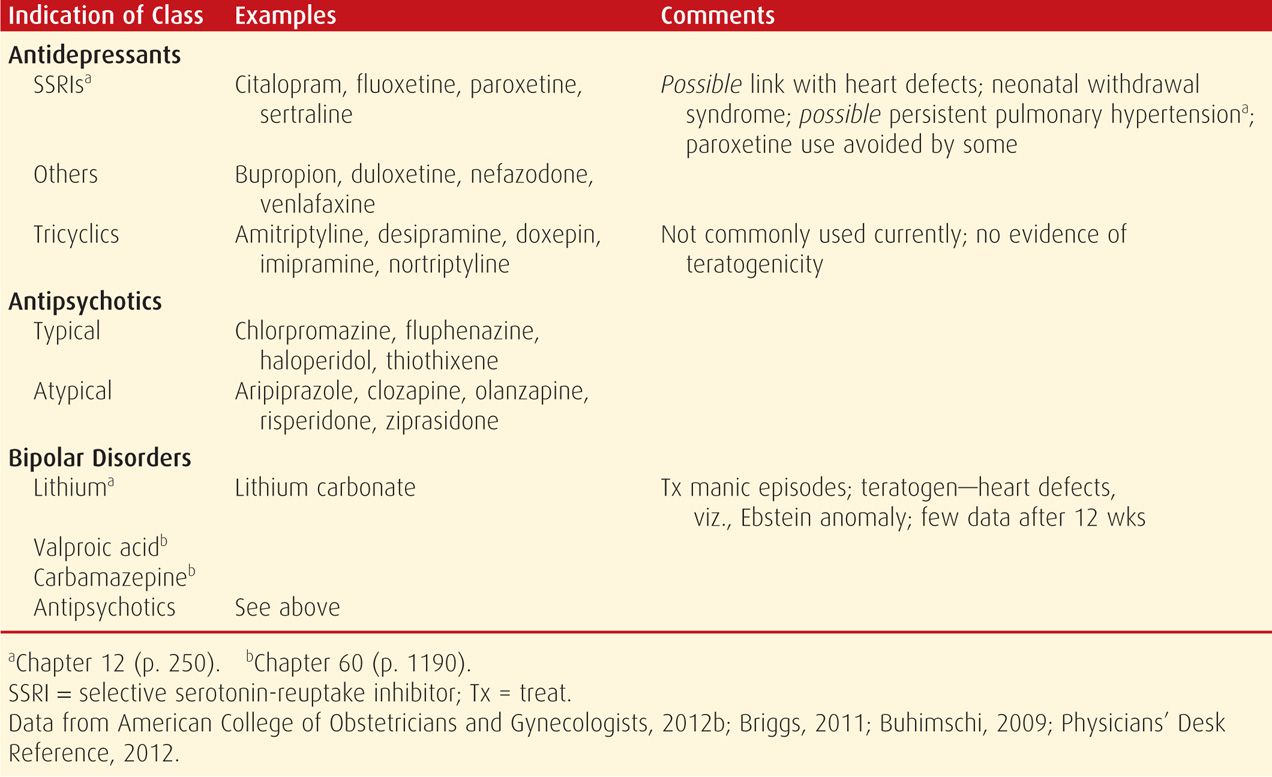

Antidepressant medications, along with some form of psychotherapy, are indicated for severe depression during pregnancy or the puerperium (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2012b). Shown in Figure 61-1 is one algorithm regarding initiation of treatment of mood disorders and management with a mental health professional. In women with severe depression a selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor—SSRI—should be tried initially (Table 61-3). Tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors are infrequently used in contemporary practice. If depressive symptoms improve during a 6-week trial, the medication should be continued for a minimum of 6 months to prevent relapse (Wisner, 2002). If the response is suboptimal or a relapse occurs, another SSRI is substituted, or psychiatric referral is considered. Mozurkewich and associates (2013) reported no salutary effects of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) to prevent perinatal depression.

FIGURE 61-1 Treatment algorithm of pregnant women with mood disorders. (Modified from Yonkers, 2011.)

TABLE 61-3. Some Drugs Used for Treatment of Major Mental Disorders in Pregnancy

Importantly, in a recent metaanalysis by Huang and colleagues (2014), women using antidepressants during pregnancy were found to be at increased risk for preterm birth and low-birthweight neonates. Nevertheless, in their review of antidepressant medication use in pregnancy, Ray and Stowe (2014) concluded that the relative reproductive safety data is reassuring and that antidepressants remain a viable treatment option.

Recurrence some time after medication is discontinued develops in 50 to 85 percent of women with an initial postpartum depressive episode. Women with a history of more than one depressive episode are at greater risk (American Psychiatric Association, 2000a). Surveillance should include monitoring for thoughts of suicide or infanticide, emergence of psychosis, and response to therapy. For some women, the course of illness is severe enough to warrant hospitalization.

Fetal Effects of Therapy

Some known and possible fetal and neonatal effects of treatment are listed in Table 61-3. Studies implicating SSRIs with an increased teratogenic risk for fetal cardiac defects were isolated to paroxetine and were most consistent for ventricular septal defects (VSDs). It is estimated that the risk is no greater than 1 in 200 exposed infants (Koren, 2012). Nevertheless, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2012b) has recommended that paroxetine be avoided in women who are either pregnant or planning pregnancy. Fetal echocardiography should be considered in women exposed to paroxetine in the first trimester.

In a case-control study, there was a sixfold increased risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) in infants exposed to SSRIs after 20 weeks (Chambers, 2006). This translates to an overall risk of pulmonary hypertension that would be less than 1 in 100 exposed infants (Koren, 2012). In contrast, a population-based cohort study of 1.6 million pregnancies from Nordic countries identified a twofold increased risk in exposed neonates. It was estimated that this yields an attributable risk of 2 per 1000 births (Kieler, 2012). This marginally increased risk must be weighed against the risk associated with discontinuing or tapering medication during pregnancy.

Women who abruptly discontinue either serotonin- or norepinephrine-reuptake inhibitor therapy typically experience some form of withdrawal. Not surprisingly, up to 30 percent of exposed neonates may also exhibit withdrawal symptoms. Symptoms are similar to opioid withdrawal, but typically are less severe. This condition—neonatal behavioral syndrome—is self-limited, and the newborn rarely remains in the nursery more than 5 days. (Koren, 2009). Currently, convincing evidence of long-term neurobehavioral effects of fetal exposure to these medications is lacking (Koren, 2012).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree