Chapter 12 Prolapse and Urogynaecology

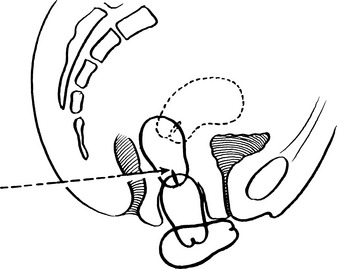

Retroversion of the uterus

Anteverted Uterus

The uterus is approximately at right angles to the vagina and has a slight forward curve.

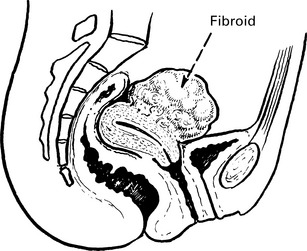

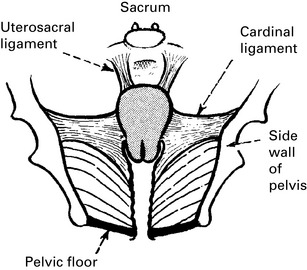

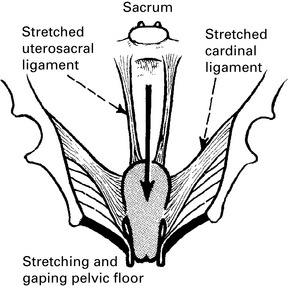

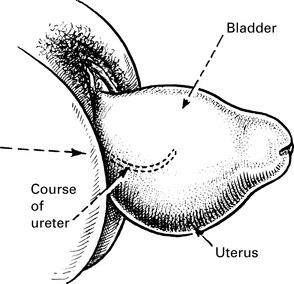

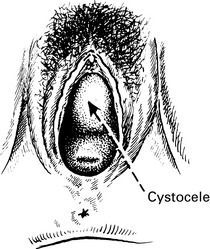

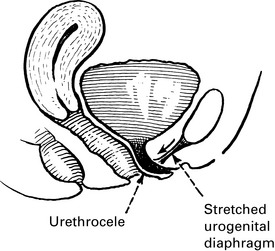

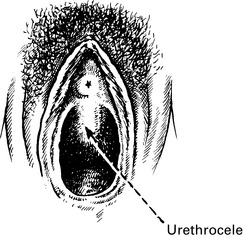

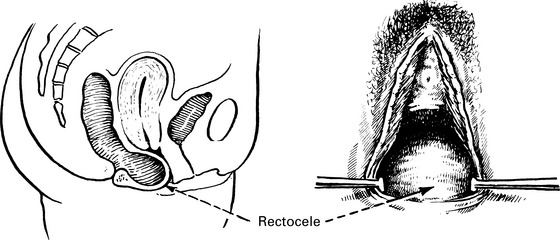

Uterovaginal prolapse

Herniation of the genital tract through the pelvic diaphragm.

The causes of prolapse are the following:

• The stretching of muscle and fibrous tissue which occurs with childbirth and damage to the innervation of the pelvic floor.

• Increased intra-abdominal pressure, for example, chronic cough, heavy manual work; congenital predisposition to stretch the ligaments.

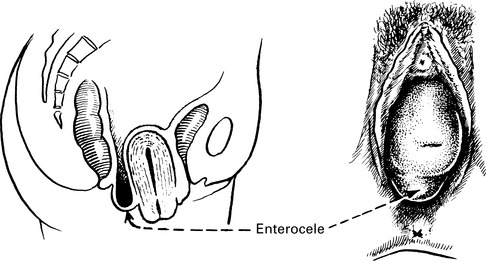

• Distortion of pelvic anatomy by previous surgery, for example, vault prolapse after hysterectomy or entercoele after colposuspension.

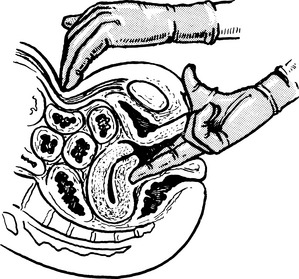

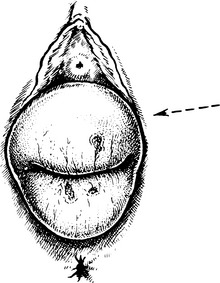

Uterovaginal prolapse

First degree: cervix still inside vagina.

Second degree: the cervix appears at the level of the introitus.

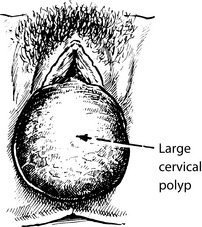

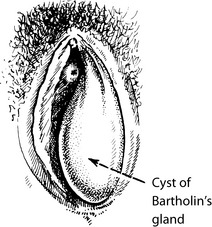

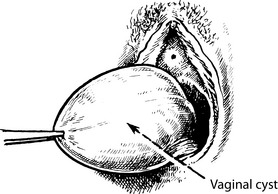

Clinical features of prolapse

• Asymptomatic. It is not uncommon for women to palpate a prolapse, for example, during washing or attempting to insert a tampon. For some women, simple reassurance that there is no sinister cause is all that is required. It can also be identified during routine smear, etc., and if asymptomatic no treatment is required.

• ‘Something coming down’ within the vagina is the commonest symptom. It tends to be worse when the woman has been on her feet and it disappears when she lies down.

• Backache. Some women will experience a dragging feeling or bearing down sensation. This is sometimes resolved with treatment of the prolapse, but mechanical back pain is very common and it may be unrelated to prolapse.

• Coital problems. This is relatively unusual but the woman may admit to difficulties with intercourse, only on direct questioning.

• Increased frequency of micturition. This can be due to anatomical changes that make it difficult to empty the bladder fully. Detrusor instability is also common in older women and may co-exist. A careful urinary history should be taken including fluid and caffeine intake.

• Stress incontinence. This is by no means always present. Sometimes, it is found that reduction of the prolapse causes stress incontinence.

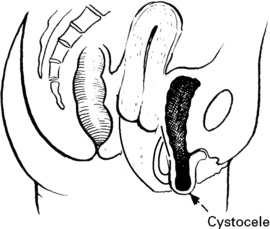

• Difficulty in voiding urine and defecating. The patient may find that it is impossible to initiate micturition except by pushing up the cystocele with her finger. In the same way, the rectocele must be pushed back to allow emptying of the rectum.

Pessary treatment

Indications for pessary treatment

• The patient prefers a pessary. Pelvic surgery with its unavoidable risks should only be applied to a willing patient.

• The prolapse is amenable to pessary support. If the perineal muscles are very deficient they will not hold a pessary and the pessary will fall out. If too big a ring is required, the vaginal wall or cervix will prolapse through it. Posterior vaginal wall prolapses are poorly supported by pessaries.