FIGURE 31-1 Total and primary cesarean delivery (CS) rates and vaginal birth after previous cesarean (VBAC) rate: United States, 1989–2010. Epochs denoted within rectangles represent contemporaneous ongoing events related to these rates. (Data from National Institutes of Health: NIH Consensus Development Conference, 2010; Martin, 2012a,b).

As the vaginal delivery rate increased, so did reports of uterine rupture-related maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality (McMahon, 1996; Sachs, 1999). These dampened prevailing enthusiasm for a trial of labor and stimulated the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (1998) to caution that such trials should be attempted only in appropriately equipped institutions with physicians readily available to provide emergency care. Less than a year later, the College (1999) recommended that physicians should be immediately available. Many believe that this one-word change—from readily to immediately available—was in large part responsible for the decade-long decline in national VBAC rates illustrated in Figure 31-1 (Cheng, 2014; Leeman, 2013). The VBAC rate leveled at approximately 8 percent by 2009 and 2010, while the total cesarean delivery rate increased to 32.8 percent in 2011 (Martin, 2011, 2012a,b). Because the success rate of a trial of labor resulting in a VBAC is not 100 percent, another way of examining these changes was described by Uddin and colleagues (2013). These investigators reported the proportion of women with a prior cesarean delivery who underwent a trial of labor. This number peaked in 1997, when slightly more than half of all of these women chose a trial of labor. Thereafter, this percentage plummeted and reached a nadir of about 16 percent in 2005. Since that time, the proportion has increased and averaged 20 to 25 percent through 2009. Ironically, during this same decade, there were continuing reports that described the success and safety of VBAC in selected clinical settings.

In reality, there are several other interrelated factors—both medical and nonmedical—that have undoubtedly contributed to declining VBAC rates. Because of their complexity and importance, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the Office of Medical Applications of Research (OMAR) convened a National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Panel (2010) to study these issues. The Panel report included a contemporaneous summary concerning the risks and benefits of repeat cesarean versus vaginal delivery. These findings are subsequently described along with summaries of current recommendations by various professional organizations. However, data from California indicate that VBAC rates have not perceptibly increased since the 2010 NIH Consensus Conference that encouraged greater access to a trial of labor after cesarean delivery (Barger, 2013).

FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE A TRIAL OF LABOR

Delivery planning for the woman who has had a previous cesarean delivery can begin with preconceptional counseling, but should definitely be addressed early in prenatal care. Importantly, any decision arrived at is subject to continuing revisions as dictated by exigencies that arise during the course of pregnancy. Assuming no mitigating circumstances, there are two basic choices. First is a trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) with the goal of achieving VBAC. If cesarean delivery becomes necessary during the trial, then it is termed a “failed trial of labor.” A second choice is elective repeat cesarean delivery (ERCD). This includes scheduled cesarean delivery as well as unscheduled but planned cesarean delivery for spontaneous labor or another indication.

Selection should consider factors known to influence a successful trial of labor as well as benefits and risks. In general, appropriately selected women who attempt VBAC have success rates that approximate 75 percent. These rates vary between institutions and providers and are affected by prepregnancy, antepartum, intrapartum, and nonmedical factors.

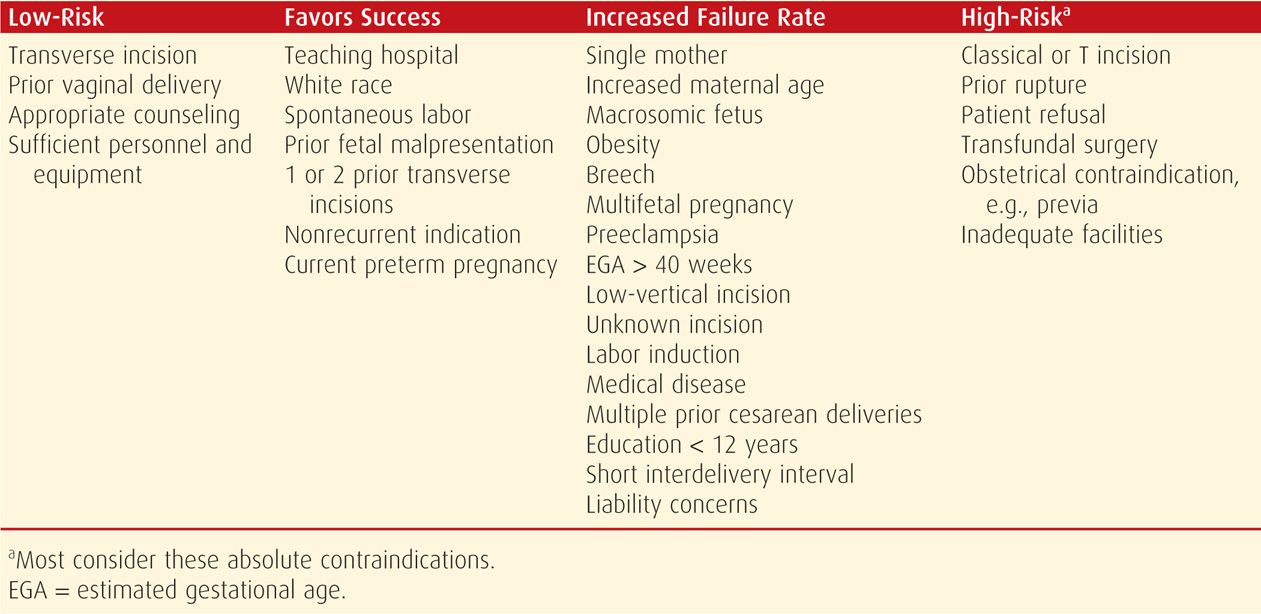

Some medical variables that influence a successful trial of labor are listed in Table 31-1. As for economical and medicolegal factors, professional liability concerns and insufficient resources to provide adequate staffing for hospitals to accommodate a trial of labor weigh heavily.

TABLE 31-1. Some Factors That Influence a Successful Trial of Labor in a Woman with Prior Cesarean Delivery

TRIAL OF LABOR VERSUS REPEAT CESAREAN DELIVERY

As evidence mounted that the risk of uterine rupture and perinatal morbidity and mortality might be greater than expected, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (1988, 1998, 1999, 2013a) issued updated Practice Bulletins supporting labor trials but also urging a more cautious approach. It is problematic that both options have risks and benefits to mother and fetus but that these are not always congruent.

Maternal Risks

Maternal Risks

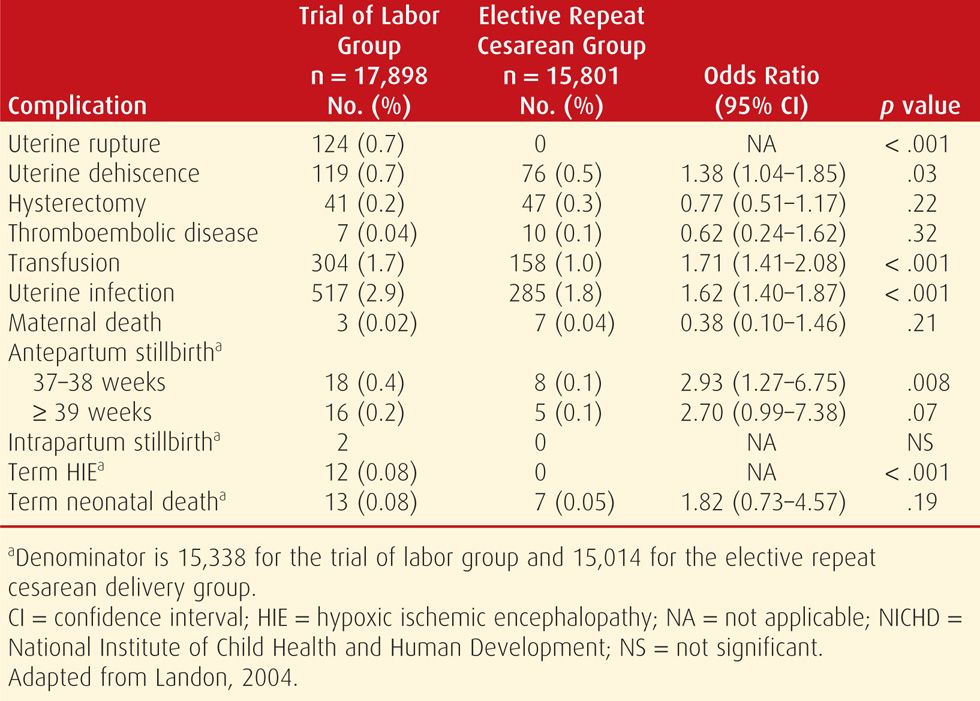

Uterine rupture and its associated complications clearly are increased with a trial of labor. It is this increased risk that underpins most of the angst in attempting a trial of labor. Despite this, some have argued that these factors should weigh only minimally in the decision to attempt a trial because their absolute risk is low. One of the largest and most comprehensive studies designed to examine risks associated with vaginal birth in women with a prior cesarean delivery was conducted by the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network (Landon, 2004). In this prospective study conducted at 19 academic medical centers, the outcomes of nearly 18,000 women who attempted a trial of labor were compared with those of more than 15,000 women who underwent elective repeat cesarean delivery. As shown in Table 31-2, although the risk of uterine rupture was higher among women undergoing a trial of labor, the absolute risk was small—only 7 per 1000. To the contrary, however, there were no uterine ruptures in the elective cesarean delivery group. Not surprisingly, rates of stillbirth and hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy were significantly greater in the trial of labor arm. Others have reported similar results (Chauhan, 2003; Mozurkewich, 2000). In one study of nearly 25,000 women with a prior cesarean delivery, perinatal death risk was 1.3 per 1000 among the 15,515 women who had a trial of labor (Smith, 2002). Although the absolute risk is small, it is 11 times greater than the risk found in 9014 women with a planned repeat cesarean delivery.

TABLE 31-2. Complications in Women with a Prior Cesarean Delivery Enrolled in the NICHD Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network, 1999–2002

Most studies suggest that the maternal mortality rate does not differ significantly between women undergoing a trial of labor compared with those undergoing an elective repeat cesarean delivery (Landon, 2004; Mozurkewich, 2000). One outlier was a retrospective cohort study of more than 300,000 Canadian women with a prior cesarean delivery (Wen, 2005). In this study, the maternal death rate for women undergoing an elective repeat cesarean delivery was 5.6 per 100,000 compared with 1.6 per 100,000 for those having a trial of labor.

Estimates of maternal morbidity have also produced conflicting results. In the metaanalysis by Mozurkewich and Hutton (2000), women undergoing a trial of labor were approximately half as likely to require a blood transfusion or hysterectomy compared with those undergoing repeat cesarean delivery. Conversely, in the MFMU Network study, Landon and coworkers (2004) observed that the risks of transfusion and infection were significantly greater for women attempting a trial of labor (see Table 31-2). Rossi and D’Addario (2008) reported similar findings in their metaanalysis. McMahon and associates (1996), in a population-based study of 6138 women, found that major complications—hysterectomy, uterine rupture, or operative injury—were almost twice as common in women undergoing a trial of labor compared with those undergoing an elective cesarean delivery. Importantly, compared with a successful trial of labor, the risk of these major complications was fivefold greater in women whose attempted vaginal delivery failed. The metaanalysis cited above also reported an increased incidence of overall maternal complications when women with a failed vaginal delivery were compared with those undergoing successful vaginal delivery—17 versus 3 percent, respectively (Rossi, 2008). Similar findings have been reported from the Network Cesarean Registry (Babbar, 2013).

Fetal and Neonatal Risks

Fetal and Neonatal Risks

The Panel found little or no evidence regarding short- and long-term neonatal outcomes after TOLAC versus ERCD. Most of the available evidence documents differences comparing actual rather than intended mode of delivery and is of low quality. A trial of labor is associated with significantly higher perinatal mortality rates compared with ERCD—perinatal mortality rate 0.13 versus 0.05 percent; neonatal mortality rate 0.11 versus 0.06 (Guise, 2010). A trial of labor also appears to be associated with a higher risk of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) than ERCD. The Maternal-Fetal Medicine Networks Unit study reported the incidence of HIE at term to be 46 per 100,000 trials of labor compared with zero cases in women undergoing ERCD (Landon, 2004).

Analysis of pooled data suggests that the absolute risk of transient tachypnea of the newborn is slightly higher with ERCD compared with TOLAC—4.2 versus 3.6 percent (Guise, 2010). But, neonatal bag and mask ventilation was used more often in infants delivered following TOLAC than in those delivered by ERCD—5.4 versus 2.5 percent. Finally, there are no significant differences in 5-minute Apgar scores or neonatal intensive care unit admissions for infants delivered by TOLAC compared with those delivered by ERCD. Birth trauma from lacerations is more commonly seen in infants born by ERCD.

Maternal versus Fetal Risks

Maternal versus Fetal Risks

Relative risks for mother and baby differ between modes of delivery. Regarding overall risks, the Panel (2010) concluded that in a hypothetical group of 100,000 women of any gestational age who undergo TOLAC, there will be 4 maternal deaths, 468 cases of uterine rupture, and 133 perinatal deaths. In comparison, in a hypothetical group of 100,000 women of any gestational age who undergo ERCD, there will be 13 maternal deaths, 26 uterine ruptures, and 50 perinatal deaths.

Despite potential concerns of increased complications, an elective repeat cesarean delivery is considered by many women to be preferable to a trial of labor. Frequent reasons include the convenience of a scheduled delivery and the fear of a prolonged and potentially dangerous labor. In an earlier study, Abitbol and colleagues (1993) found that these preferences persisted despite extensive antepartum counseling.

CANDIDATES FOR A TRIAL OF LABOR

There are few high-quality data available to guide selection of trial of labor candidates (Guise, 2004; Hashima, 2004). That said, having fewer complicating risk factors increases the likelihood of success (Gregory, 2008). Several algorithms and nomograms have been developed to aid prediction, but none has demonstrated reasonable prognostic value (Grobman, 2007b, 2008, 2009; Macones, 2006; Metz, 2013; Srinivas, 2007). Use of a predictive model for failed trial of labor, however, was found to be somewhat predictive of uterine rupture or dehiscence (Stanhope, 2013). Despite these limitations for precision, several points are pertinent to the evaluation of these women and are described in the next sections. Current recommendations of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2013a) are that most women with one previous cesarean delivery with a low-transverse hysterotomy are candidates, and if appropriate, they should be counseled regarding a trial of labor versus elective repeat cesarean delivery.

Prior Uterine Incision

Prior Uterine Incision

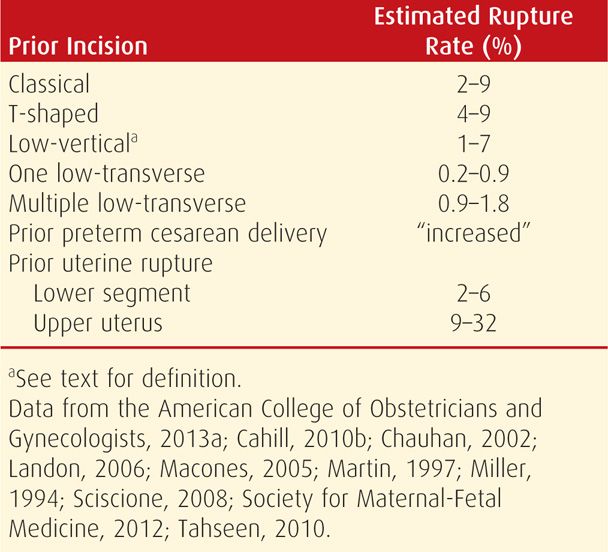

Prior Incision Type

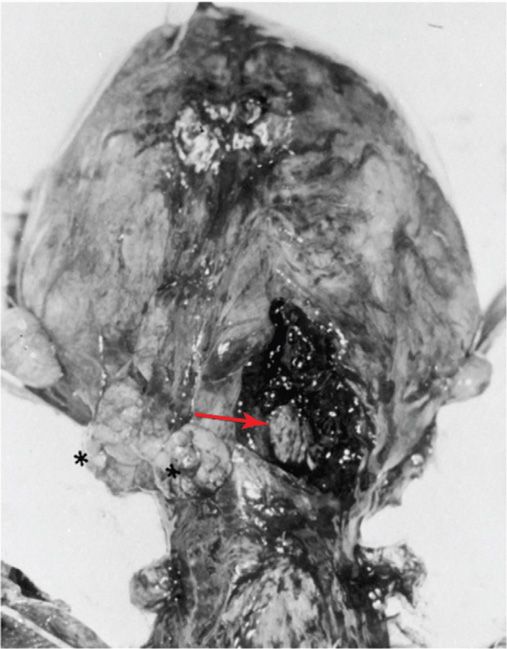

The type and number of prior cesarean deliveries are overriding factors in recommending a trial of labor. Women with one prior low-transverse hysterotomy have the lowest risk of symptomatic scar separation (Table 31-3). The highest risks are with prior vertical incisions extending into the fundus, such as the classical incision shown in Figure 31-2 (Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine, 2013). Importantly, in some women, the classical scar will rupture before the onset of labor, and this can happen several weeks before term. In a review of 157 women with a prior classical cesarean delivery, one woman had a complete uterine rupture before the onset of labor, whereas 9 percent had a uterine dehiscence (Chauhan, 2002).

TABLE 31-3. Types of Prior Uterine Incisions and Estimated Risks for Uterine Rupture

FIGURE 31-2 Ruptured vertical cesarean section scar (arrow) identified at time of repeat cesarean delivery early in labor. The two black asterisks to the left indicate some sites of densely adhered omentum.

The risk of uterine rupture in women with a prior vertical incision that did not extend into the fundus is unclear. Martin (1997) and Shipp (1999) and their coworkers reported that these low-vertical uterine incisions did not have an increased risk for rupture compared with low-transverse incisions. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2013a) concluded that although there is limited evidence, women with a prior vertical incision in the lower uterine segment without fundal extension may be candidates for a trial of labor. This is in contrast to prior classical or T-shaped uterine incisions, which are considered by most as contraindications to labor.

Currently, there are few indications for a primary vertical incision (Osmundson, 2013). In those instances—for example, preterm breech fetus with an undeveloped lower segment—the “low vertical” incision almost invariably extends into the active segment. It is not known, however, how far upward the incision has to extend before risks become those of a true classical incision. It is helpful in the operative report to document its exact extent.

Prior preterm cesarean delivery may have an increased risk for rupture. Although the type of prior incision was not known, Sciscione and associates (2008) reported that women who had a prior preterm cesarean delivery were twice as likely to suffer a uterine rupture compared with those with a prior term cesarean delivery. This may be in part explained by the increased likelihood with a preterm fetus of extension of the uterine incision into the contractile portion. Conversely, Harper and colleagues (2009) did not find a significantly increased rate of rupture during subsequent VBAC in women with a prior cesarean delivery performed at or before 34 weeks.

There are special considerations for women with uterine malformations who have undergone cesarean delivery. Earlier reports suggested that the uterine rupture risk in a subsequent pregnancy was increased compared with the risk in those with a prior low-transverse hysterotomy and normally formed uterus (Ravasia, 1999). But, in a study of 103 women with müllerian duct anomalies who had one prior cesarean delivery and who attempted a trial of labor, there were no cases of uterine rupture (Erez, 2007). Given the wide range of risk for uterine rupture associated with the various uterine incision types, it is not surprising that most fellows of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists consider the type of prior incision to be the most important factor when considering a trial of labor (Coleman, 2005).

Prior Incision Closure

As discussed in Chapter 30 (p. 596), the low-transverse hysterotomy incision can be sutured in either one or two layers. Whether the risk of subsequent uterine rupture is affected by these is unclear. Chapman (1997) and Tucker (1993) and their associates found no relationship between a one- and two-layer closure and the risk of subsequent uterine rupture. And although Durnwald and Mercer (2003) also found no increased risk of rupture, they reported that uterine dehiscence was more common after single-layer closure. In contrast, Bujold and coworkers (2002) found that a single-layer closure was associated with nearly a fourfold increased risk of rupture compared with a double-layer closure. In response, Vidaeff and Lucas (2003) argued that experimental models have not demonstrated advantages of a double-layer closure and that the evidence is insufficient to routinely recommend a double-layer closure. At Parkland Hospital we routinely suture the low-segment incision with one running locking suture.

Number of Prior Cesarean Incisions

There are at least three studies that reported a doubling of the rupture rate—from approximately 0.6 to 1.85 percent—in women with two versus one prior transverse hysterotomy incision (Macones, 2005a; Miller, 1994; Tahseen, 2010). In contrast, analysis of the MFMU Network database by Landon and colleagues (2006) did not confirm this. Instead, they reported an insignificant difference in the uterine rupture rate in 975 women with multiple prior cesarean deliveries compared with 16,915 women with a single prior operation—0.9 versus 0.7 percent, respectively. As discussed subsequently, other serious maternal morbidity increases along with the number of prior cesarean deliveries (Marshall, 2011).

Imaging of Prior Incision

Sonographic measurement of a prior hysterotomy incision has been used to predict the likelihood of rupture with a trial of labor. Large defects in the hysterotomy scar in a nonpregnant uterus forecast a greater risk for rupture (Osser, 2011). Naji and associates (2013a,b) found that the residual myometrial thickness decreased as pregnancy progressed and that rupture correlates with a thinner scar. From their review, however, Jastrow and coworkers (2010) found no ideal thickness to be suitably predictive. The optimal safe threshold value for the lower uterine segment—smallest measurement from amnionic fluid to bladder—ranged from 2.0 to 3.5 mm. For the myometrial layer—smallest measurement of the hypoechoic portion of the lower segment, it was 1.4 to 2.0 mm. With a lower segment < 2.0 mm, the risk of uterine rupture was increased 11-fold. With myometrial thickness < 1.4 mm, uterine rupture was increased fivefold. The measurements, however, are not predictive for an individual woman (Bergeron, 2009).

Prior Uterine Rupture

Prior Uterine Rupture

Women who have previously sustained a uterine rupture are at increased risk for recurrence during a subsequent attempted VBAC. As shown in Table 31-3, those with a previous low-segment rupture have a 2- to 6-percent recurrence risk, whereas prior upper segment uterine rupture confers a 9- to 32-percent risk (Reyes-Ceja, 1969; Ritchie, 1971). We believe that women with a prior uterine rupture or classical or T-shaped incision ideally should undergo repeat cesarean delivery when fetal pulmonary maturity is assured, and preferably before the onset of labor. They should also be counseled regarding the hazards of unattended labor and signs of possible uterine rupture.

Interdelivery Interval

Interdelivery Interval

Magnetic resonance imaging studies of myometrial healing suggest that complete uterine involution and restoration of anatomy may require at least 6 months (Dicle, 1997). To explore this further, Shipp and colleagues (2001) examined the relationship between interdelivery interval and uterine rupture in 2409 women who had one prior cesarean delivery. There were 29 women with a uterine rupture—1.4 percent. Interdelivery intervals of ≤ 18 months were associated with a threefold increased risk of symptomatic rupture during a subsequent trial of labor compared with intervals > 18 months. Similarly, Stamilio and coworkers (2007) noted a threefold increased risk of uterine rupture in women with an interpregnancy interval of < 6 months compared with one ≥ 6 months. But they also reported that interpregnancy intervals of 6 to 18 months did not significantly increase the risk.

Prior Vaginal Delivery

Prior Vaginal Delivery

Prior vaginal delivery, either before or after a cesarean birth, significantly improves the prognosis for a subsequent vaginal delivery with either spontaneous or induced labor (Grinstead, 2004; Hendler, 2004; Mercer, 2008). Prior vaginal delivery also lowers the risk of subsequent uterine rupture and other morbidities (Cahill, 2006; Hochler, 2014; Zelop, 2000). Indeed, the most favorable prognostic factor is prior vaginal delivery.

Indication for Prior Cesarean Delivery

Indication for Prior Cesarean Delivery

Considering all women who elect trial of labor, 60 to 80 percent will have a successful vaginal delivery (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2013a). Women with a nonrecurring indication—for example, breech presentation—have the highest success rate of nearly 90 percent (Wing, 1999). Those with a prior cesarean delivery for fetal compromise have an approximately 80-percent success rate, and for those done for labor arrest, success rates approximate 60 percent (Bujold, 2001; Peaceman, 2006). Prior second-stage cesarean delivery can be associated with second-stage uterine rupture in a subsequent pregnancy (Jastrow, 2013).

Fetal Size

Fetal Size

Most studies show that increasing fetal size is inversely related to successful trial of labor. The risk for uterine rupture is less robust. Zelop and associates (2001) compared the outcomes of almost 2750 women undergoing a trial of labor, and 1.1 percent had a uterine rupture. The rate increased—albeit not significantly—with increasing fetal weight. The rate was 1.0 percent for fetal weight < 4000 g, 1.6 percent for > 4000 g, and 2.4 percent for > 4250 g. Similarly, Elkousy and colleagues (2003) reported that the relative risk of rupture doubled if birthweight was > 4000 g. Conversely, Baron and coworkers (2013a) did not find increased uterine rupture with birthweights > 4000 g.

Fetal size at the opposite end of the spectrum may increase the chances of a successful VBAC. Specifically, women who attempt a trial of labor with a preterm fetus have higher successful VBAC rates and lower rupture rates (Durnwald, 2006; Quiñones, 2005).

Multifetal Gestation

Multifetal Gestation

Perhaps surprisingly, twin pregnancy does not appear to increase the uterine rupture risk with trial of labor. Ford and associates (2006) analyzed the outcomes of 1850 such women and reported a 45-percent successful vaginal delivery rate and a rupture rate of 0.9 percent. Similar studies by Cahill (2005) and Varner (2007) and their colleagues reported rupture rates of 0.7 to 1.1 percent and vaginal delivery rates of 75 to 85 percent. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2013a), women with twins and a prior low-transverse hysterotomy who are otherwise candidates for vaginal delivery can safely undergo a trial of labor.

Maternal Obesity

Maternal Obesity

Obesity decreases the success rate of trial of labor. Hibbard and coworkers (2006) reported the following vaginal delivery rates: 85 percent with a normal body mass index (BMI), 78 percent with a BMI between 25 and 30, 70 percent with a BMI between 30 and 40, and 61 percent with a BMI of 40 or greater. Similar findings were reported by Juhasz and associates (2005).

Fetal Death

Fetal Death

Most women with a prior cesarean delivery and fetal death in the current pregnancy would prefer a VBAC. Although fetal concerns are obviated, available data suggest that maternal risks are increased. Nearly 46,000 women with a prior cesarean delivery in the Network database had a total of 209 fetal deaths (Ramirez, 2010). There were 76 percent who had a trial of labor with a success rate of 87 percent. Overall, the rupture rate was 2.4 percent. Four of five ruptures were during induction in 116 women with one prior transverse incision—3.4 percent.

LABOR AND DELIVERY CONSIDERATIONS

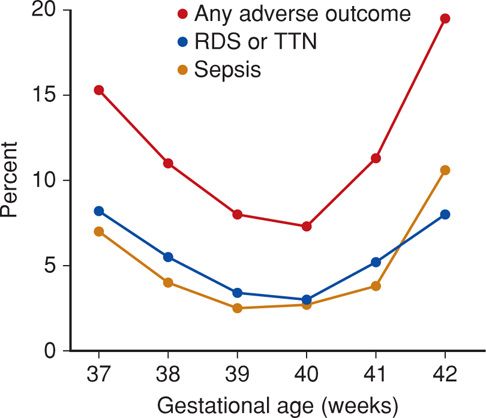

If elective repeat cesarean delivery is planned, it is essential that the fetus be mature. As shown in Figure 31-3, significant and appreciable adverse neonatal morbidity has been reported with elective delivery before 39 completed weeks (Chiossi, 2013; Clark, 2009; Tita, 2009). The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2012) have established the following guidelines for timing an elective operation, and at least one of these three must be documented:

1. Ultrasound measurement < 20 weeks supports a gestational age of ≥ 39 weeks.

2. Fetal heart sounds have been documented for 30 weeks by Doppler ultrasound.

3. A positive serum or urine β-hCG test result has been documented for ≥ 36 weeks.

FIGURE 31-3 Neonatal morbidity and mortality rates seen with 13,258 elective repeat cesarean deliveries. Any adverse outcome includes death. Sepsis includes suspected and proven. RDS = respiratory distress syndrome; TTN = transient tachypnea of the newborn. (From Tita, 2009.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree